Elephant’s Associate Editor, Emily Burke, speaks with Anne Imhof on the evening before she leaves New York after the conclusion of DOOM.

There have been many visions of how the world will end, but few begin with the imposition of oligarchy on a high school prom. This is how Anne Imhof sets up DOOM: House of Hope, her sprawling epic which showed at the Park Avenue Armory in New York last week.

Most of us were first introduced to Anne with FAUST when she represented Germany at the 2017 Venice Biennale. Retrospectively, FAUST laid out a “beginners guide” to the artist’s worldbuilding. Eliza Douglas was there from the get-go, strumming a guitar and looking dissociative. There were heavy-handed references to fascism that made everybody in the pavilion squirm. Dobermans? In the German pavilion? It was 2017, and fascism still shocked us back then.

Of course the world has changed since 2017, and Anne has changed, too. Once the queen of understatement, Imhof’s DOOM was nothing short of a spectacle. Based loosely on a reverse telling of Romeo and Juliet, DOOM incorporated live music, ballet, tattooing, a type of choreography called ‘bone-breaking’ (which looks as painful as it sounds), and a flank of black Cadillac Escalades.

Over DOOM’s three-hour performance, we saw Anne’s ambitions run wild. It was a world of her own creation, but even there, Romeo and Juliet could only defy death by returning to the very beginning again.

Emily Burke: You’re still in New York, right?

Anne Imhof: Yes, I’ve been here for a while now, living in hotel rooms and developing a habit of eating burgers at night, but that’s okay. I’m very much in love with New York.

EB: The city is almost a microcosm of its own. What’s your relationship like with America more generally? I ask because Americana was such a prevalent theme in DOOM.

AI: I made DOOM with New York in mind. I have lived in America for quite some time now and have a deep relationship with it, just like I do with Berlin. It’s my second home. But, of course, DOOM was also shown at a time when the American president is attempting to become an autocrat, or has already become an autocrat.

EB: I was going to ask you whether DOOM had been directly impacted by the news cycle over the last few months.

AI: It wasn’t directly impacted, as in, we didn’t change the piece to reflect the news. But it certainly has informed it. Over the weeks that we spent in New York, certain aspects of the piece took on different meanings, took on different significance. The piece evolves over the course of it being shown, and it changes with every show.

To me, the stronghold of the cast of DOOM and sense of a safe space was palpable, as well as a shared belief in a better more hopeful future. The artists seemed to be carrying themselves in a fierce but gentle manner – very energetic towards the audience but also very gentle. So maybe that was the result of taking in the news over the last few months? The state is affecting all of us on a day-to-day basis, even if it’s fear that’s being instilled in us, that’s making us feel isolated. Resistance against a state that is violating its citizens is also growing day by day.

EB: When you say the performance evolves, what do you mean? How are you deciding what to alter? Are you watching the audience’s reaction and seeing how it’s impacting them, or is it more intuitive?

AI: It’s a very collaborative process between me and the cast. I watch how the audience reacts – that’s one part of it. But things also just occur to me as it runs. For example, I really wanted Xavier [Days] to have a solo moment during DOOM, but we couldn’t find the space during rehearsals. Then, on opening night, it occurred to me that there is this moment when the audience walks past the centre stage, and the circular stage is empty. So, I immediately texted Xavier, like, “If you feel it, take that solo stage and do the solo now!” When he got to the stage it was really brightly lit, but within moments it went pitch black, because that’s how we had previously cued it. So he started the solo in the bright light, and then he was in pitch black doing a style of dance called ‘bone-breaking’. At first I was like, Holy shit what do I do? But then I looked at it and thought, This is actually quite beautiful.

I knew that Eliza [Douglas] was free, so I asked her to shine a light at him with her phone’s torch. On her way down from the car stage she was on, I also gave her my phone, which resulted in these two phones circling Xavier. It was such a beautiful addition to the piece that we decided to keep it for the following performances. That’s the thing, especially with performers like Xavier and Eliza who are so excellent at improvisation; the moment itself is actually the most beautiful, so much so that it loses something the more it’s repeated.

EB: Coming back to the narrative of DOOM, the piece loosely tells the story of Romeo and Juliet, but in reverse. Why does this tale feel important for these times?

AI: Romeo and Juliet is the love story for all times, and the text is actually very open and forgiving. It allows for isolating and reshaping certain aspects of the story – like taking Romeo and Juliet’s love story and turning it around, starting with their deaths and ending with their meeting. It’s a more hopeful trajectory.

There are two houses in the play, and they could both stand for different things. But there are also these young people, Romeo and Juliet, who die so young and who don’t survive because their love isn’t wanted in the world.

EB: Yeah, just total, senseless loss.

AI: Exactly. It’s a story that has repeated itself throughout history, and it’s a story that we’re going to be faced with over and over again if things don’t change. Juliet and Romeo are everyone who is suffering from hate and violence against them and the ones whom they love and desire romantically. It’s a dark time for America and for many parts of the world, but… there will be new romance. It’s the time for it – and our time as artists to show it and stand up for it, to tell ancient stories differently and make new images from them so people can see how beautiful and free it could be.

EB: There is this inherent darkness to DOOM: the space is dark and cavernous, there are these black Cadillac Escalades in the space which are usually driven by oligarchs – and, obviously, the name is quite literally “doom”. But the piece is ostensibly about love and hope. Why did it feel necessary to explore light through darkness?

AI: It wasn’t easy to formulate, and I worked very closely with Niklas Bildstein Zaar from the architecture studio sub on this. We wanted to find a way to open the gates of the Armory and bring the streets inside. We wanted there to be an unsettling environment, as a reflection of what is happening right now. But the rest of the space was set up like a gymnasium, or a college gym, like we had a prom night or a college party happening. So, while the cars were supposed to be dark and unsettling, we wanted to make it clear that hopefulness could still happen in dark and unsettling times.

People have the power to say something when they stand together. They can never be underestimated. People in power have the potential to single out individuals; they can attack them about the gender, their race and their origins. They can try to discipline them and use violence against them, like the government is doing right now, but I believe that they’re doing this because the people in power know that they’re in an unstable position. I really believe that the bee stings before it dies.

EB: I was going to ask if you think we’re doomed, but it sounds like maybe you don’t?

AI: [Laughs] I really don’t know. I do, and I don’t.

EB: I want to talk about the reception of DOOM. Is there anything you feel people have gotten wrong about the project?

AI: I don’t think people can get it wrong. Once something is out there, it’s no longer mine to determine what it is or what it says. I was mostly just humbled and incredibly grateful for how many people saw and thought about DOOM in such different ways. Negative criticism is a necessity if a piece is discussed and even if it hurts to read it, and I do care – it can be a real blessing for me. This is the beauty of a piece like this; it moves people in different ways. It was really important for me to include the role of the critic in DOOM, played by a young woman who cites obituaries of critics working in the past – like important dance critics from The New York Times. Of course, I wish people had witnessed this project from the very beginning to the very end, but I think that ultimately, everyone is creating their own edit while watching, and this is how we intended it to be. They can change the narrative by moving in the space.

Of course, there were people who were angry about the piece. But that’s kind of just a continuation of what I have experienced, very sadly, on the streets. When you’re queer and you show your love openly, especially two very beautiful young women, certain people don’t feel included – men especially can get very angry and violent. People ultimately choose what it is that they see in DOOM.

EB: Is there anything in particular that you have learnt from DOOM that you’ll be taking into your next project?

AI: There’s so much. In particular, working with the ballet and the dancers of ABT as an artist was such a dream – it’s a dream to be able to collaborate with a discipline whose rules you don’t fully know and to be met with such generosity from the people you work with. I also love this juxtaposition between performance art and ballet. I can’t wait another three years to make a new piece this time – there’s an urgency now. I want to continue working with these people.

EB: I was just going to ask, are you already thinking about your next project?

AI: One hundred percent. I wake up in the morning in this state between dreaming and being fully awake, still thinking about things that I want to put into the piece – movement and melodies and what I want to work on with the artists – and then I slowly realise that DOOM is over. So, it’s good that there’s a next piece coming in the future. There are so many ideas coming to me, it can be overwhelming at times.

EB: How does it feel to have finished DOOM? Is there a comedown period? Are you coming back to earth?

AI: There’s definitely a certain melancholy that comes with ending a piece, and I think we’re all in a state of comedown. But on the other hand, this piece originated so close to real life that even though the curtain is closed, I feel the show is still going on. To be honest, I think we’ve all gone a bit mad. Like, [laughs] Eliza just came into the hotel room wearing her full look, like she just came off stage. This is the sort of thing that’s been going on. I guess we’re all just very in love with the world right now and with doing this piece together. At one point, half of the cast, including me, were getting tattoos like “WE HOPE,” the date of the show, “House of Hope” – people even had my name tattooed. I got “Romeo” tattooed on my chest… I just looked around and thought, Guys, are we losing our minds?

Words by Emily Burke

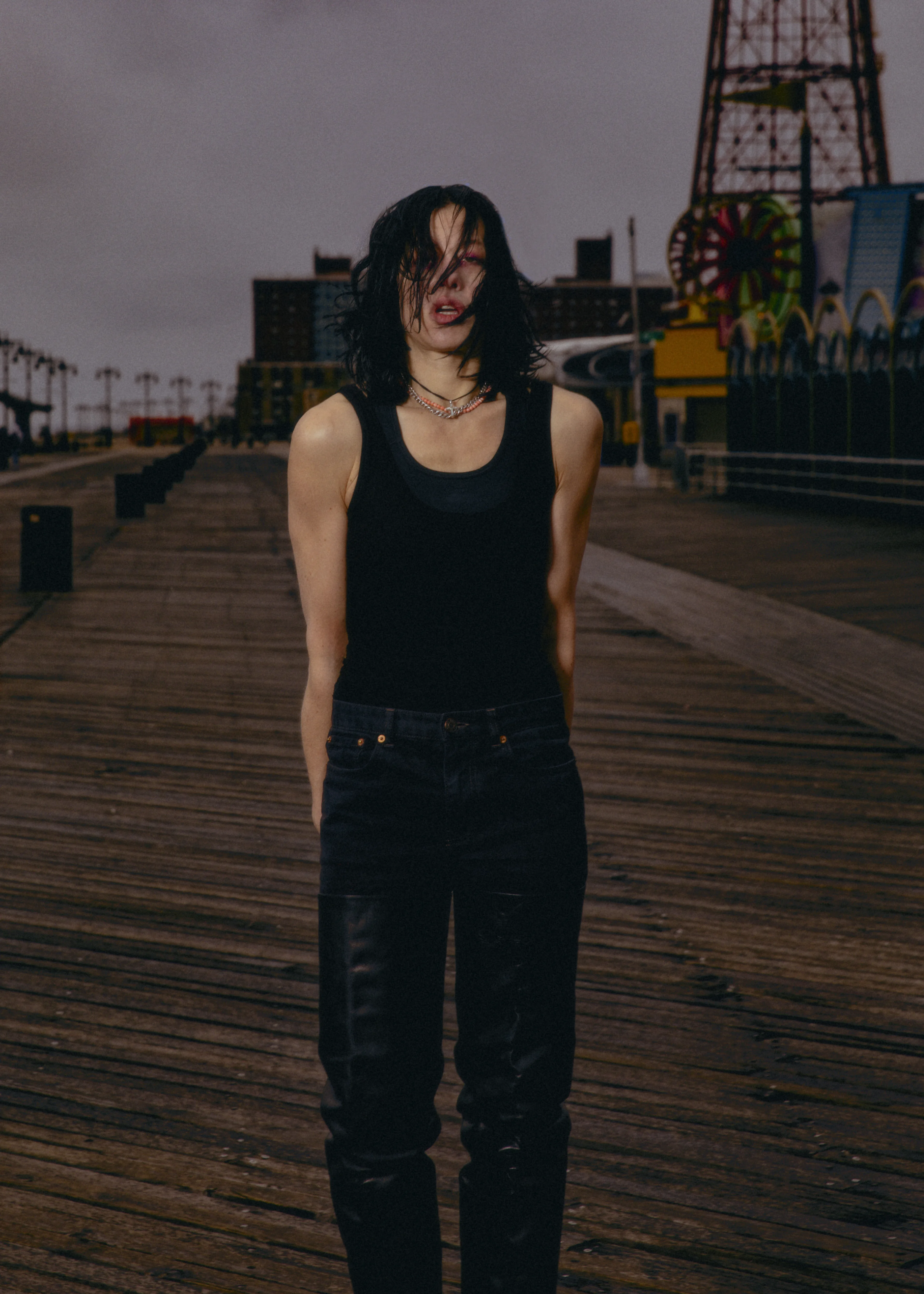

Photography by Nadine Fraczkowski