Ella Slater reviews the rebellious and mystical films of Marguerite Duras from the ICA’s ongoing summer retrospective.

Whenever you see a truck passing, it is a woman’s words that go by – Jean-Luc Godard on Marguerite Duras.

It was L’Amant (The Lover, 1984) which led me to Marguerite Duras. It took about two years of shelf-surfing before I decided to push past the pouty red cover and Lolita-ish description to actually read the book, though I’d later wish I had done so sooner. The Lover is indelibly erotic and perverse: the semi-autobiographical tale of an affair between an adolescent French girl and an older Chinese businessman, taking place in the French-colonial Indochina of Duras’s childhood. A decade after its release, to the writer’s distaste, it found itself as the subject of a Jacques Annaud film adaptation, one which focused largely—and rather predictably—on sex. And so it was through dissatisfaction with others’ adaptations of her literature that Duras found herself as a filmmaker (or perhaps, as she once outrageously argued, it was just a way to “fill the time”).

Consequently, the publication by Another Gaze Editions of My Cinema– which coincides with a retrospective of Duras’s moving image work at the ICA– is particularly poignant. My Cinema, as described by Another Gaze’s Daniella Shrier, is “autobiography, political and historical reportage, and a 400-page defence of an art form”; an insight into Duras’s filmic craft as she might want us to experience it: in her own words. Her movies were almost the opposite of their predecessors: unashamedly unconcerned with their audience, and staunchly anti-commercial. It might be more accurate to describe them as anti-cinema, since ostensibly, nothing much happens within them: a tango is played, a glance is exchanged, or a walk is taken. Often, their only narrative progression is the passing of time. Yet in their defiant nature, they form both a phantasmagoric cross-section of human complexity and an investigation into the medium of cinema itself.

I – GHOSTS

“When you say that memory is the subject of a film, it doesn’t mean anything,” Duras once said. “Memory is there, everywhere, all the time, an enormous gulf that surrounds us.” Duras’s ‘Indian Cycle,’ a series of three films made after a trio of books written between 1964 and 1971, were all, as Shrier explains, set in the “mythical ‘S. Thala’ – a coastal town she invented as a substitute for the Indochina of her childhood – and preoccupied with the same story of ‘a love affair paralysed at the height of passion,’ which she had apparently heard about as a child.” Duras’s autobiography is inseparable from her art: a ghostly presence, if you like. Shrier continues: “nearly everything she wrote and filmed goes back to biographical data such as her poor childhood in French Indochina, her mother who was sold the colonial promise but was made destitute there, her violent elder brother, her early involvement with the Communist Party, and her guilt over surviving the Second World War.”

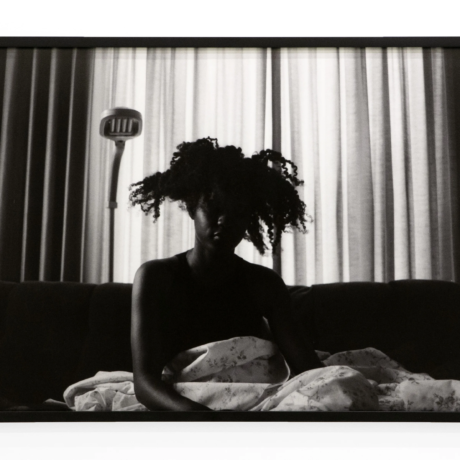

If memory is encompassing, it is also an echo chamber, or perhaps a prison, and fittingly, Duras’s films can be claustrophobic things. Baxter, Vera Baxter (1976) takes place within the confines of a sprawling mid-century villa, an impersonal container for a tale of conjugal despair, re-lived through an afternoon of conversation. In this villa, the only constant is time. To watch Baxter, Vera Baxter is to traverse the past in a waltz towards the protagonist’s impending (or perhaps already passed) suicide. This is, then, a vampiric, self-consuming cinema: a folding inwards of past, present and future; life and death.

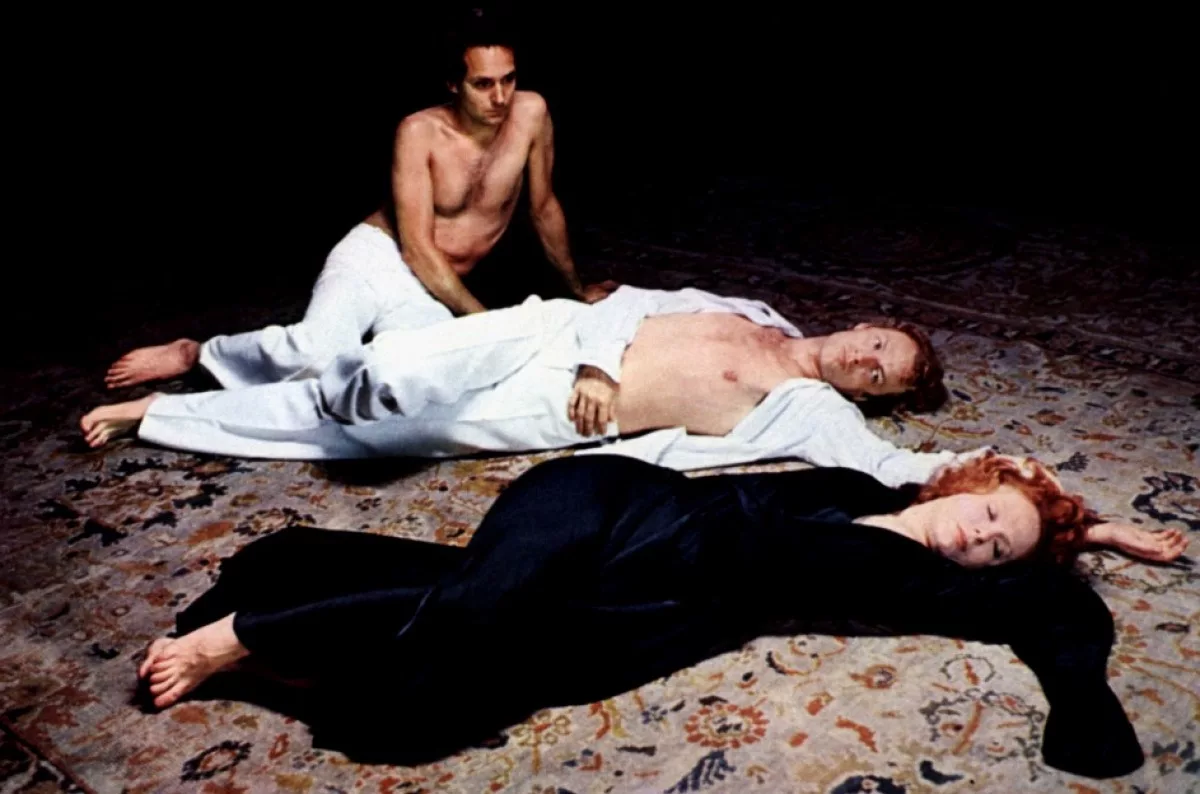

One of the aforementioned ‘Indian Cycle’ films, and Duras’s best known feature, is India Song (1975), itself– as Shrier explains– “an adaptation of a play she’d written, whose performance she cancelled after the film’s shoot, knowing it could never rival the film to be.” This a real ghost story: lyrical and haunting, and beginning (as well as ending) with death. Death runs parallel to the film: in flowers on mantle pieces, photographic shrines to different women (all of them the movie’s protagonist– “it is impossible to represent her… I can communicate one possible image, or ‘one of many possible versions’, as André Breton would say”), and in colonial India. India Song is also a love story, and a horror story, of ennui (“leprosy of the soul”), as well as the leprosy and famine coalescing in the monsoon season of its invisible colonial India which is always present, never seen.

In a perverse cinematic approach, it is the unseen which unites much of Duras’s filmography. What is described often fails to materialise. Baxter, Vera Baxter’s story takes place in an afternoon of dialogue. India Song is more complex: a complete fracturing of audio and visual, through characters which never open their mouths. Instead, their story is told by onlookers, at as much distance from the subjects as us, the film’s audience (“where are we?” one of the narrators asks). Duras’s notes on the feature read: “And so with the star and the viewer made distant in the same way, the two finally meet.” Since they never speak, the people we watch may not even be the characters described; they are, like the figures of Duras’s past, ghosts.

The separation of the seen and heard also revokes the superiority of the visual, replacing it with language, and forcing us to listen. Duras’s filmic career was spent pushing back against what she saw as cinema’s failure to merge image and text successfully. In an interview about Le Camion (The Lorry, 1977), she proclaimed: “It is not by chance that the verbal quality of the word is usually denied by cinema. Cinema which, having never been able to replace the text, nevertheless tries to replace it.” Like Pauline Oliver’s Quantum Listening, which posits the radical potential of listening to transform the social matrix, Duras found in the audible a route to transform film.

II – WITCHES

A monologue from Baxter, Vera Baxter: “Witches have come like that. During the Middle Ages, men were at wars, the Crusades, and country women remained alone, isolated, months and months in huts in the forest… It is in this solitude that they start speaking to trees, plants, inventing an intelligence with nature. They were called sorceresses and were burned. One of them was called Vera Baxter.” Duras’s protagonists, predominantly women, feel their environments deeply. They are their environments (“she [Anne-Marie Stretter] is Calcutta”). They are also Duras herself, embodiments of both hysteria and pain. Some might say they are mad, others: witches (the terms, at times, have been interchangeable).

Madness is a recurring theme throughout Duras’s filmography; she once said that “a madman is an individual who transgresses an essential prejudice, namely the limits of the ‘I.’” Duras’s exploration of the psyche was inextricably entwined with her political beliefs, and the ‘transgression of I’ a method of radical rebellion. Of Destroy, she said, Duras wrote: “‘Is it a political film?’ ‘Yes, profoundly.’ ‘Is it a film where politics are never evoked?’ ‘Yes, never’.” Destroy, she said’s characters are simultaneously individual and interchangeable, involved in a dissolution of self which Duras called “capital destruction.” It is a kind of utopian tabula rasa— the title of Alice Blackhurst’s introduction to My Cinema—and emblematic of Duras’s idealistic approach to a form of communism, which she would be involved with throughout her life.

It was, however, following her estrangement from the formal Communist Party in the 1950s that Duras became disillusioned with forms of membership and labelling, which in turn would make her feminism notably complex. She refused to explicitly align herself with the movement, instead involving herself in an arts journal which she helped name: the feminist writer and academic Xavière Gauthier’s Sorcières. “Why witches?”, its opening letter reads, “Because witches dance… because witches are alive… because witches are rapturous.” Watching Duras’s movies is certainly an experience of rapture: they are hypnotic and rhythmic, propelled by poetic dialogue and soundtracks, like the devastatingly seductive jazz melody of India Song. As Shrier says, “Duras’s cinema is also a cinema of desire, in which women’s longing is neither analysed nor moralised.” In fact, it was India Song which the journalist Molly Haskell described as “the most feminine film I have ever seen.”

Letting cinema go to its ruin might otherwise be said to kill it, but Duras’s work is less blunt, more sensual, than this. Hers is a kind of erotic cinematic sorcery, immortalised in the shorts, features, televisual work and contributions on view as part of the ICA’s retrospective, or in the conversations and musings of My Cinema. Perhaps only a writer could have approached the medium in this way: as a saboteur (a witch), determined to fracture the audio-visual in favour of language. Perhaps—as she might argue— this could only have been done by Duras. Regardless, this is ‘film’ as an artistic and intellectual investigation, into the very nature, and the making (or eventual ruin), of the medium of cinema itself.

Words by Ella Slater