Rain has arrived in London following a heatwave, and there is nothing like a cold drizzle in September to signal the end of summer. With it comes a shift in mood, and a return to responsibility and to “normality”—or so those in government would have us think. Specifically, there has been much discussion in recent weeks over the return to the workplace. Long commutes and sad lunchtime sandwiches aside, numerous workers have raised their voices in dissent at the prospect of being forced to fit themselves to the rigid shape of office life once more. A recent YouGov poll found that just 25 percent of workers aged 25 to 49 supported a return to the office.

Lockdown has seen an overdue loosening of the snug proportions of the status quo, and former patterns have been disrupted. Just as the BLM protests brought calls for greater representation and diversity in the workplace and beyond, so has the mass experiment in working from home introduced new possibilities for the fundamental ways in which commerce, travel and community can be approached. During this period, I have found myself with more time to spend in my local area during the day, rather than returning to it only after dark following a long journey home from the office. I have been more alert and less exhausted, no longer shuttling from one side of the city and back again, clocking in and clocking out.

“When it comes to creative work, I have rarely trusted clocks as a useful measure of productive time”

When it comes to creative work, I have rarely trusted clocks as a useful measure of productive time. A question I often ask artists about their work is, “But how do you know when each piece is finished?”, and no one has yet answered with a set formula. Research for an artwork, film or academic paper can advance suddenly with a breakthrough, or else crawl for weeks on end with little progress. For better or worse, creative pursuits are never linear, and to apply a set beginning and end to them is often facile. Likewise, the 9 to 5 working day has long been irrelevant, particularly in an age when digital communication has all but done away with the boundaries between the home, the commute and the office.

There are other fallacies that have been stripped away during this period, too. The inconsistencies of the art world are increasingly out in the open, laid painfully bare by the pandemic. Striking front of house workers at the Tate face mass redundancies, while senior and managerial staff continue to collect paychecks, some more than £100,000 each year; over 400 staff were laid off yesterday at the National Theatre, while many hundreds more across the culture sector will be made redundant in the coming months.

“Artists, thinkers, writers, curators, etc., like anyone living in a capitalist world, have no choice but to be ethically inconsistent, but inconsistencies are even more explicit in our smaller artworld, and the proximity of these contradictions to our personal lives is rarely mitigated,” artist Tai Shani wrote this week in Art Review. She takes aim not just at the working structures of galleries and museums but at the aggressively neoliberal business model of art schools (Shani works as a tutor at the Royal College of Art), which systemically contradict the progressive politics they proclaim to teach. She argues for an art world that rejects the hypocrisies that have been so deeply ingrained in it over years of public cuts and privatisation, and one which allows for genuinely radical thought.

“The culture of overwork, of profiteering and of severe pay gaps in the art world is no longer viable”

We are living in a moment where the past is under greater scrutiny than ever, and the journey taken to where we now stand is being retraced and reevaluated. Statues are toppled, and the colonial origins of nations are unravelled. No more are former mistakes accepted as the norm, and the culture of overwork, of profiteering and of severe pay gaps in the art world is no longer viable. I have the impression of constant movement, of push and pull, but I worry that instead of change this is just a cyclical motion within a machine that is too big to truly derail.

The art world operates on an international scale, while movement in the most literal of senses has been greatly reduced. International travel to biennales, art fairs and gallery weekends has been halted by high-profile cancellations of these events, and it seems unlikely that the circuit will resume untouched in future. The status quo is fading. Many artists, among others in the industry, are moving away from capital cities, and away from the high cost of living that invariably comes with them.

The system might not have been shattered yet, but more of its workers are speaking up against it through both actions and words. It is not always easy to look directly at the inequalities of the industry, which are now displayed in plain view, but it is necessary if progress is to be made. Rather than running in circles, it is time for hard truths.

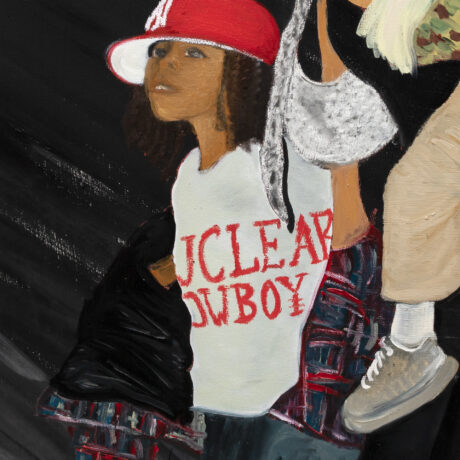

Are We There Yet is a fortnightly column by Louise Benson. Top image © Aparna Sarkar