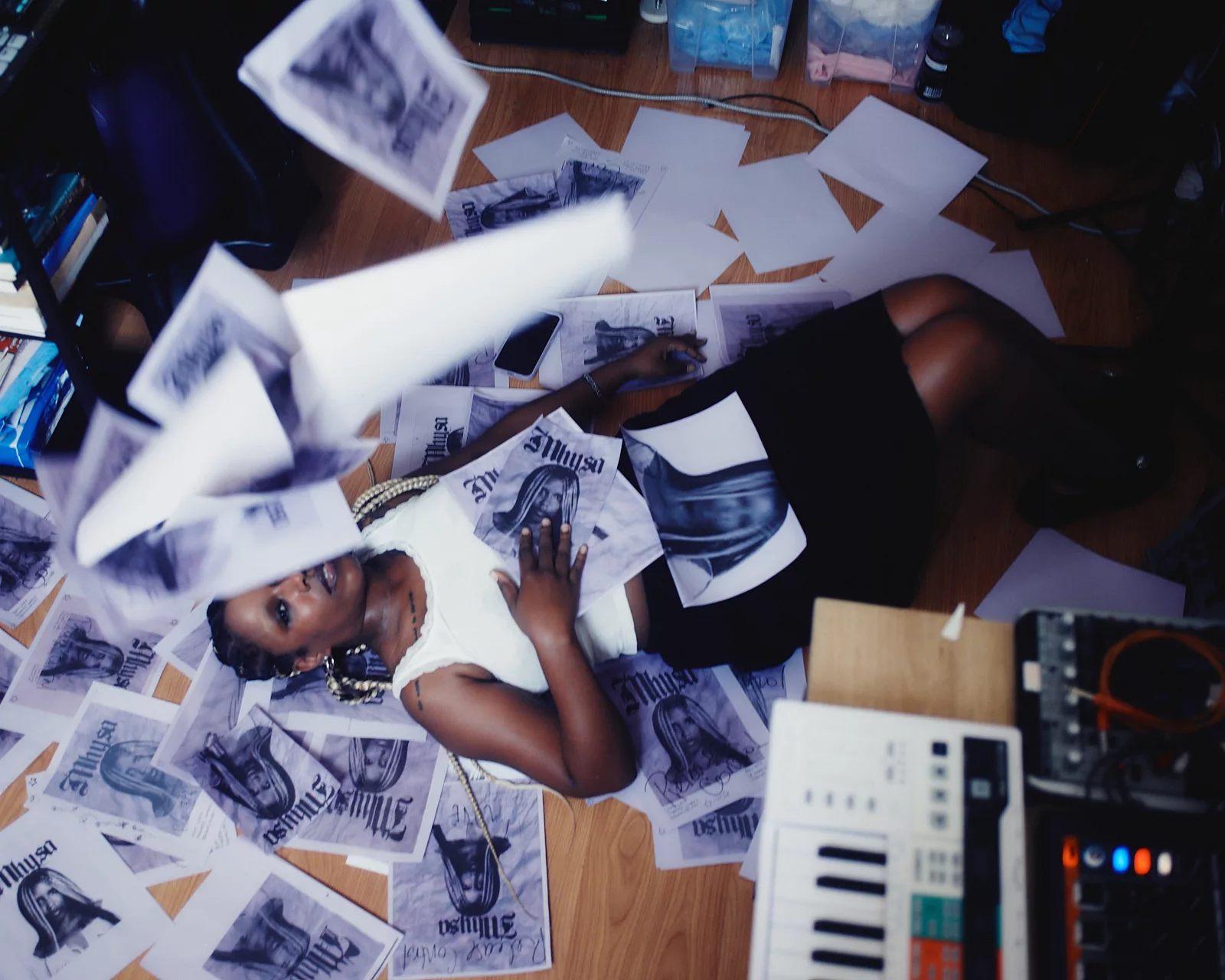

MHYSA puts her body on the line. The underground pop star’s musical output is a work towards an enlightened divadom. Her recent third album, “Release Control,” is a synthesis of Southern rap, experimental pop, R&B, and ambient electronic music.

The New York-based musician is the alter ego of the multidisciplinary artist E. Jane, who has spent their career exploring the labour and cultural output of Black divas: Whitney Houston, Janet Jackson, and Beyonce. (Jane uses they/them pronouns, while MHYSA uses she/her.) Jane’s universe is technicolour and rhythmic: luminescent pink and lavender hues set to a soundtrack of vocal powerhouses. “I’m not just judging these women from afar. I want to see how hard it is,” says Jane as they prepare for MHYSA’s upcoming performance at Pioneer Works curated by Jane Ursula Harris.

Jane’s world — and MHYSA’s by default — is steeped in past and present history, hours of research filtered through fantasy grounded in the vision of a more empathetic future that centres the inner lives of Black women. Through their loving and meticulous archive, Jane arrives at a new framework for understanding American history: a safe space for Black women that challenges thinly veiled cultural moments of systemic racism, sexism, and media surveillance.

MHYSA is a decade-long embodiment of Jane’s practice; she is constantly evolving, leaving a trail of her genesis online and through Jane’s work.

To talk about the two personas inhabited by one artist is difficult but necessary in order to understand their respective efforts. One day, will the lines between their music, visual art, and identity blur? Will E. Jane and MHYSA collapse into each other, forming a composite of artist-researcher and musician-performer? Or will they grow steadily on their own islands, accruing creative signifiers so singular that their creative personas will crystalize? In the present day, Jane’s first solo museum exhibition, “Drenched in Light,” at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and MHYSA’s recently released album, “Release Control,” are kindred spirits, joined by a lifelong inquiry into Black excellence and empowered womanhood.

Jane’s interest in divadom dates back to their childhood. They came to consciousness online as an only child in the suburbs of Prince George’s County, Maryland, surrounded by conservative Southern Baptist culture. From an early age, they were obsessed with the music of bonafide stars of the 90s: Brandy, Monica, Janet Jackson, Erykah Badu, Lauryn Hill, Whitney Houston, Chaka Khan and Mariah Carey. (When they were 9-years-old, they began burning tapes of R&B they heard on the radio.)

During middle school, Jane learned how to shoot and edit videos. “Talking through video really started for me there. It was the first language that I felt articulate in,” they reflect. Their interests in digital spaces and music came to fruition while they were in the MFA program at the University of Pennsylvania, where they found solace from the predominantly white spaces of academia through music as well as with a community of Black women and femme graduate students and artists they met online.

“I am not grappling with notions of identity and representation in my art. I’m grappling with safety and futurity. We are beyond asking if we should be in the room. We are in the room,” Jane declared in their 2015 “NOPE Manifesto.” The statement originated as a Facebook status after they attended Fred Moten’s lecture on “Blackness and Nonperformance” at MoMA, where, for the first time, they experienced a physical space that centred a community of Black luminaries such as Glenn Ligon, Coco Fusco, and Saidiya Hartman.

Inspired, they began an ongoing exploration of physical space underscored by a list of utopian demands: “We need more people, we need better environments, we need places to hide, we need utopian demands, we need a culture that loves us.” Their manifesto hurdles past the limiting binaries of identity art and outlines an expansive notion of Blackness, queerness, creativity, history, and of a sustainable future. “I reject the colonial gaze as the primary gaze. I am outside of it in the land of NOPE,” they wrote.

Around the same time as they wrote NOPE, Jane created #CindyGate, a call for discussion and critique of the artist Cindy Sherman’s early self-portraits wearing blackface. “#Cindygate reflects larger systemic issues in art, spec. whose body is expected in the gallery + whose body matters,” they Tweeted of the racist contextualization that the works seemed to have largely evaded.

Today, Jane uses the Internet to subvert and disseminate ideas around Black excellence. They live out their utopian demands through their work. “In a state where Black people are expected to be hypervisible, the right to hide when you want is already a utopian demand. How do we refuse that surveillance? How do we play with that surveillance?” they ask.

“I remember there was a shift between my first and second year of grad school. where I was like, ‘I want to work in video, but I don’t know what I want to talk about, but I kept watching these music videos.'” Jane recalls the music video for “Trippin,'” a song by R&B girl group Total and Missy Elliott that they watched on loop in 2016. “I thought, the women are in these pink frilly outfits, and they’re being really sexy, but they’re just with themselves,” they say. “That was really exciting to me.”

MHYSA was born “in that middle space between doing a live experimental electronic set and performing for myself in the house.” Her first album came out in 2017, and she began touring soon after. In a sort of artistic osmosis, they manoeuvre between chronicling artists like Summer Walker to channelling her.

“When I think of MHYSA, I think of the term Gesamtkunstwerk, the total art of everything,” says Jane. “I’m making the cover art, I’m playing with merch, and the promo images. It’s all in-house right now,” adding that this also includes the tradition of working with collaborators to bring their vision to life: in this case, Dreamcrusher did the album design.

As Jane has developed MHSYA’s image and sound, they have collaborated with photographers such as Naima Green, Elle Pérez, and Elliott Jerome Brown Jr. Today, collaboration still pulses through the project. They began working on their forthcoming EP with their life/work partner chukwumaa (together, the two make up the performance duo SCRAAATCH) and fellow musicians Abdu Ali and Bapari in the summer of 2020 after they arrived in Brooklyn from Philadelphia. Around the same time, they began taking vocal lessons with Nicholas Ryan Gant.

“I’m thinking about my own interiority in some ways, how my interior needs relate to performance,” Jane offers. “I root it in her because I’m thinking about myself a bit, like what needs to be put back into me? But then I am also thinking about how divas have performed divadom over the years,” they say.

Going on tour as MHYSA opened up Jane’s eyes to the level of work expected from the performers they studied. “The language that agents use made me think a lot about the relationship between America’s colonial past and music,” they say. “There’s still language that agents use, words like buying talent, that are really nefarious to me.

The term diva originated in the nineteenth century to describe the lead female singer in opera (there was also the divo for men), Jane explains. Now, the word is often associated with a misogynistic, negative connotation: a woman, often Black, whose ambition and self-worth overshadow her talent. Today, the term’s colloquial use, they suggest, tells us more about America’s limited understanding of what a successful Black woman should deserve and strive for.

Jane’s four-dimensional work often creates a dialogue between the countless Black women who have blazed the trail for a new generation of performers like MHYSA. They place performances and video essays in immersive yet decluttered installations: subjects’ names have been painted on walls, photos printed on fabric and hung from the ceiling, monitors placed on the floor like giant iPhones and soft seats planted in front of projections.

In the case of “Where there’s love overflowing,” their exhibition and performance last year at New York venue the Kitchen, visitors took turns standing inside a shimmering, pink tulle bag to watch a recording of MHYSA’s live-streamed performance “When I Think of Home, I Think of a Bag.” (She originally sang the cover of “Home” from The Wiz from inside the same bag at Canada Gallery.) MHYSA’s closing night rehearsal happened during gallery hours: visitors could eavesdrop on the band, but they couldn’t come in. Later, MHYSA performed “Home” with a full band for the first time.

Jane cites writer Robyn Crawford’s memoir about her friendship with Whitney Houston and Claudia Jones’s essay “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman” as key texts in understanding the expectations of Black female performers. “What could we do to be better as a world? What would it look like?” they ask.

At Boston MFA, pages of Jane’s “Diva Zine” expand onto the walls. Excerpts from Zora Neale Hurston’s writing are collaged with found images from Jane’s archive. In the middle of the room, a set of three large, round floor cushions face a wall with a projection of their video essay “LetMEbeaWomanTM.mp4,” 2020. The video begins with a glitchy black and white clip of Diahann Carroll accepting a Tony Award for Best Lead Actress for her performance in “No Strings.” Carroll made history as the first Black woman to win in that category.

“I wanted this. I really wanted this,” she says, as purple sparkles scatter across the screen as Summer Walker softly croons, “and you let me be a woman.”

Here, the notion of the diva is deconstructed, unearthing the corners of a collective psyche so often ignored or whitewashed by popular culture. Jane shows the labour that it takes to keep up the persona of divadom. They show divas present and past, like Summer Walker and Diahann Carroll, in a nonlinear dialogue, striving and excelling — tired and frustrated — as an emblem of the American dream built on the back of slavery and Black creativity and memorialised on the Internet in digital clips. The divas on screen are nuanced in their ambition. “They’re having conversations through time,” says Jane. “I’m really trying to point at how these issues are persisting today.”

French Olympic figure skater Surya Bonaly appears on screen, completing, as subtitles written by a Twitter user tell us, the hardest move on ice. “It is interesting because that footage is old, but they are making it new again on Twitter by adding emojis, by adding text, by re-contextualizing it,” says Jane, adding that the larger story is that the move was also illegal.

“That was a move that disqualified her,” they tell me. “She did that because she could never win first place, even though she was super talented and could do things that your body is not necessarily able to do. She was like, well, let me show you what I can do since I’m not going to win anyway.”

As Bonaly spins on the screen, the unrealistic expectations and public scrutiny that Black women face in the spotlight is mirrored in their private lives: an impassioned clip from Walker’s infamous Instagram live zeroes in on the singer forced to defend herself for simply stating that she preferred baths to showers.

The film’s score (an original composition by Jane that mixes Walker’s “Shame” with ethereal synths) offers a connective tissue for the clips that often double before they disappear, refracting and seeping in and out of each other’s screen time: an archive of Black femme performers pushing up against their limitations in professional spaces. “There are all these moments in “LetMEbeaWomanTM.mp4,” where I’m like: ‘I don’t think y’all heard her. Let’s play that back. Let’s slow that down,'” says Jane. At one point, an edit of Jennifer Holliday belting “You’re Gonna Love Me” is mashed up with the lyrics “Look out baby a star is a slave,” then, “I don’t wanna be free.”

“By putting those words next to each other, that’s a moment where people understand,” says Jane, “that it’s a Faustian contract, the bind that you’re in: desiring hyper-visibility in a structure that started out of colonial violence.”

Jane asks themself, “What does the empty vessel need to be filled with?” as they prepare for MHSYA’s upcoming performances.

Words by Meka Boyle