Gregor Schneider is a collector of rooms. Since the mid-1980s, the German artist has constructed and arranged dozens of chambers. With some exceptions, these resemble the sort of domestic quarters in which we live our lives. That is, if they’d been completely denuded of the comfort and security that turn a house into a home. Schneider’s homes are often drab and forlorn, all linoleum floors, net curtains and mystery stains on tablecloths. In one room, a sad-looking dormitory bed shares a narrow space with a bathtub; in another, a disco ball lords it over a decrepit basement. They’re not the sort of places in which you’d like to self-isolate.

The ongoing pandemic has made us acutely aware of a home’s shielding function. Whether huts to provide shelter or army-rebuffing castles, houses have long served as a barrier from the outside world. The walls that protect, however, can also conceal, entrap and disorientate. Schneider’s art often captures these less salubrious effects. One of his creations is a room that rotates 360 degrees while the visitor drinks a cup of coffee, without their knowledge. “So you are in a room,” the artist explains, “and you don’t know where you are anymore. You’re going on with daily life but at the same time you’re in a totally unknown space and time.”

“Schneider’s homes are often drab and forlorn, all linoleum floors, net curtains and mystery stains on tablecloths”

For 2004’s Die Familie Schneider, commissioned by Artangel, he converted two adjoining terrace houses in Whitechapel into doppelgängers, building rooms within rooms that were almost exactly parallel to each other, down to the items in the fridge. Visitors were given keys and left to enter alone. Actors performed unhinged, unnerving actions: manically dishwashing, hiding in bin bags, and masturbating in a bathtub, all done as if unobserved. These were also duplicated; Schneider went so far as to cast identical twins to maintain the illusion. “Normally,” he explains, “daily lives are something that we experience uniquely. But there you experienced a daily life that wasn’t unique anymore. This was for many people a very intense experience.”

Schneider is speaking from Haus u r, the node from which much of his output radiates. The artist has reshaped this house—which is named for its location on Unterheydener Straße in the artist’s hometown of Rheydt (now part of Mönchengladbach)—since 1985, when his parents allowed him to move into its second storey apartment. Inside its unassuming walls, Haus u r contains a labyrinth of Schneider’s rooms, some accessible and others blocked off. Several are slowly moved by machines.

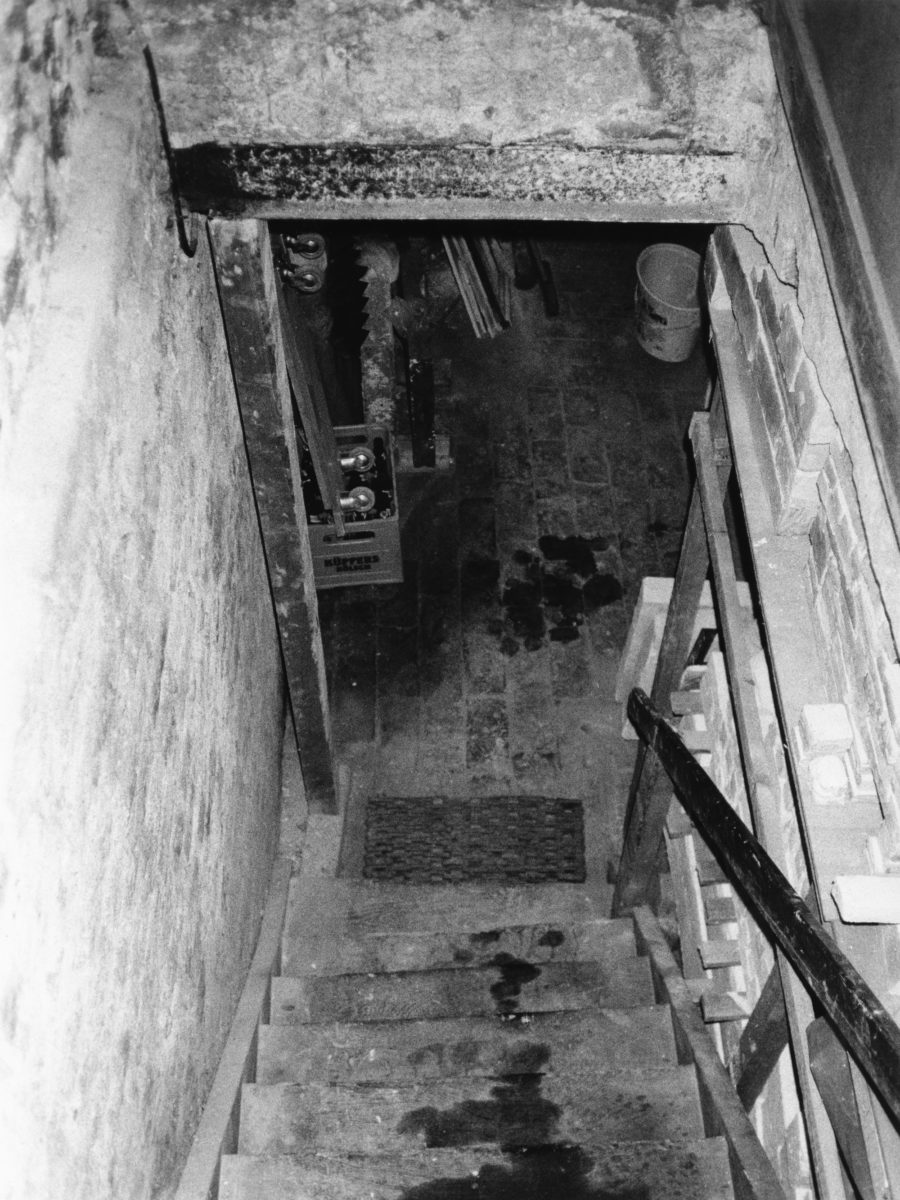

- Left: One of the pavilion’s most infamous rooms, the ‘brothel’, featured a red disco ball. Right: The staircase to Haus u r’s cellar, in 1995

The “architectural installation” has become a perennial feature of contemporary art museums. In Krefeld, about fifteen miles north-east of Rheydt, the Mies van der Rohe-designed Haus Lange and Esters contain Yves Klein’s Le Vide, a room painted entirely white. And Schneider’s endeavour has often been compared to Kurt Schwitter’s Merzbau (1923-37), where the Dadaist transformed his own family home in Hanover into an artwork. But Schneider’s work is, by his own declaration, something different: he doesn’t transmute pre-existing rooms but creates new ones.

“A room, by my definition, is built out of walls, a celling and a floor,” the artist explains, “a compete shape that surrounds you. A lot of artists speak of rooms, but they do not build rooms, they put something in an existing room.” Schneider’s rooms have their own discrete existence, even when arranged together inside a house. One of his storage depots in Rheydt is twenty metres high and filled with these complete units, ready be transported and displayed; in 2016, his retrospective at Bonn’s Bundeskunsthalle saw twenty-four of these rooms temporarily moved out. “I’m collecting rooms,” Schneider continues, “the rooms exist. And I think this is very unusual. I make rooms mobile, transportable, and I store and collect them, like paintings, like an original artwork.”

Schneider has worked with more conventional mediums. His earliest artworks, created when he was a teenager, included angry figurative pastels and acrylics: a Munch-like existentialist scream here, some fleshly, Bacon-esque forms there. He staged and filmed performances: Bury (1984) saw him dig a hole then burrow into it before replacing the soil lost, while Flour Orgy (1985) had him cake himself in a flour-based paste, which among others things lent him the aspect of a decomposing corpse.

But the Haus u r was already an outsize presence in his practice. While studying at Münster, he presented photographs of it for an exam. Working on room after room throughout the 1990s to increasing attention, he was eventually commissioned by Udo Kittelmann to exhibit at the German Pavilion at the 2001 Venice Biennale. Schneider’s contribution, Totes Haus u r, turned what had been an ever-evolving, living project into a static monument. Comprising twenty-two rooms from Rheydt rearranged inside a Nazi era pavilion, it became a sensation. “Venice was somehow at the top of all,” says Schneider, “and it made everything more public.” He was awarded the Golden Lion, and received invitations to exhibit internationally. Fragments of Haus u r made their way around the world.

Things quickly soured, however. “After the biggest success,” Schneider recounts, “I had the biggest loss in Venice. I was completely shut out of the art world.” Cube—a black, cube-shaped structure to be placed on St Mark’s Square during the 2005 Biennale—was banned after local politicians objected on political grounds, worried that its formal similarly to the Kaaba in Mecca would act as a provocation to Islamist groups. He then tried to show it at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, but once again found his work obstructed by authorities, with no public explanation for the cancellation. “Still today,” Schneider says, “there are so many things about are unspoken. We should talk about the trouble, about the fears. We should make it public.”

The work was ultimately realised outside the Hamburger Kunsthalle in 2007. Schneider insists the sculpture did not mean to cause upset. “It’s a sculpture,” he explains, “in form and function unique, it’s not a replica of the Kaaba, though it was inspired by the Kaaba, and also by Malevich’s Black Square. It stands in a chronological relationship to black rooms I’d built before.” An entirely white cube created concurrently and exhibited in Cadiz notably caused no such fuss, and several Muslim writers wrote in support of the work.

“I make rooms mobile, transportable, and I store and collect them, like paintings, like an original artwork”

This is not the only time controversy has attached itself to Schneider’s work. In 2008, a story in the Art Newspaper about his Sterberaum (‘Dying Room’)—a room intended as a space in which a person could die a natural death—set off a flurry of outraged responses. And, in the years since Venice, several of his projects appear to take a more direct, even confrontational approach to social issues. One of the most overt examples is Weisse Folter (2007), a maze of corridors and cells aiming to recreate the authoritarian architecture of Guantánamo Bay. Süßer Duft Edinburgh 2013, at the city’s international festival, interrogated racism and slavery. Visitors would pass into a pitch-dark chamber, inhabited by ten naked black actors who silently looked away from their interloper.

In light of these works, it is tempting to view all Schneider’s work through this lens. Rheydt lies in brown coal country, not far from Tagebau Garzweiler, a vast open-surface lignite mine. In past few decades, villages have been destroyed as the mine expands, with several thousand citizens shunted elsewhere. Does Haus u r’s eerie sense of abandonment evoke such places? “I wouldn’t say that I’m a political artist,” explains Schneider, “because I have too much respect for real political artists who risk their lives for their fights for democracy or for their freedom. But you could say that in the last few years the social relevance aspect has become more visible. In 2001, no one was really writing about it. And I think if I’d have mentioned Goebbels I wouldn’t have got the Golden Lion.”

- Left: For Eating, Schneider sat in the house eating soup. Right: The plot also contained a shed, in which Schneider found phrenological material

Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda, is a looming spectre in Schneider’s recent practice. While researching for the German Pavilion, Schneider discovered that Nazi minister of propaganda Joseph Goebbels’ childhood home still existed in Rheydt, despite the official line that it had been destroyed in the war. And it sat within spitting distance of Haus u r. “The strange thing,” says Schneider, “is that Haus u r looks the same from the outside. They have the same sitting room, they have the same cupboards, they have the same staircase.” Further research revealed that a picture of the house at the end of the war, with a white flag in front of it, led Goebbels to order a terror squad to attack the city’s mayor. “Because of the house,” Schneider continues, “people died. So the house is not innocent.” Local neo-Nazi groups had also discovered the house’s location, and taken to placing flowers in front of it on Goebbels’ birthdays.

“I wouldn’t say that I’m a political artist, because I have too much respect for real political artists who risk their lives for their fights for democracy”

Schneider came up with several projects based on the house, including an unsuccessful proposal to install a replica around Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth, without revealing its provenance. Then, in 2014, he bought it. He documented its contents—its garden shed included a phrenological instrument and literature—and filmed several videos of himself inside the house. One shows Schneider with a hammer, breaking up the room where Goebbels was born, an exorcism that sees the artist ensconced in thick dust, as if the past threatens to overwhelm the artist.

What Schneider then did to the house might stand as his most extensive remodelling of domestic space yet: he pulverised the house’s internal features completely, so that only the external walls are still standing. The remains were exhibited first in Warsaw and then Berlin, making the house’s hidden historical guilt bracingly visible. “Houses,” says Schneider, “are written like books. And we need to change the original material.” Schneider’s uncanny art asks us to consider the stories, real and imaginary, written into the walls that surround us. As the world slowly re-emerges from weeks of home confinement, his interrogation of these structures seem more apposite than ever.

All images courtesy of Gregor Schneider