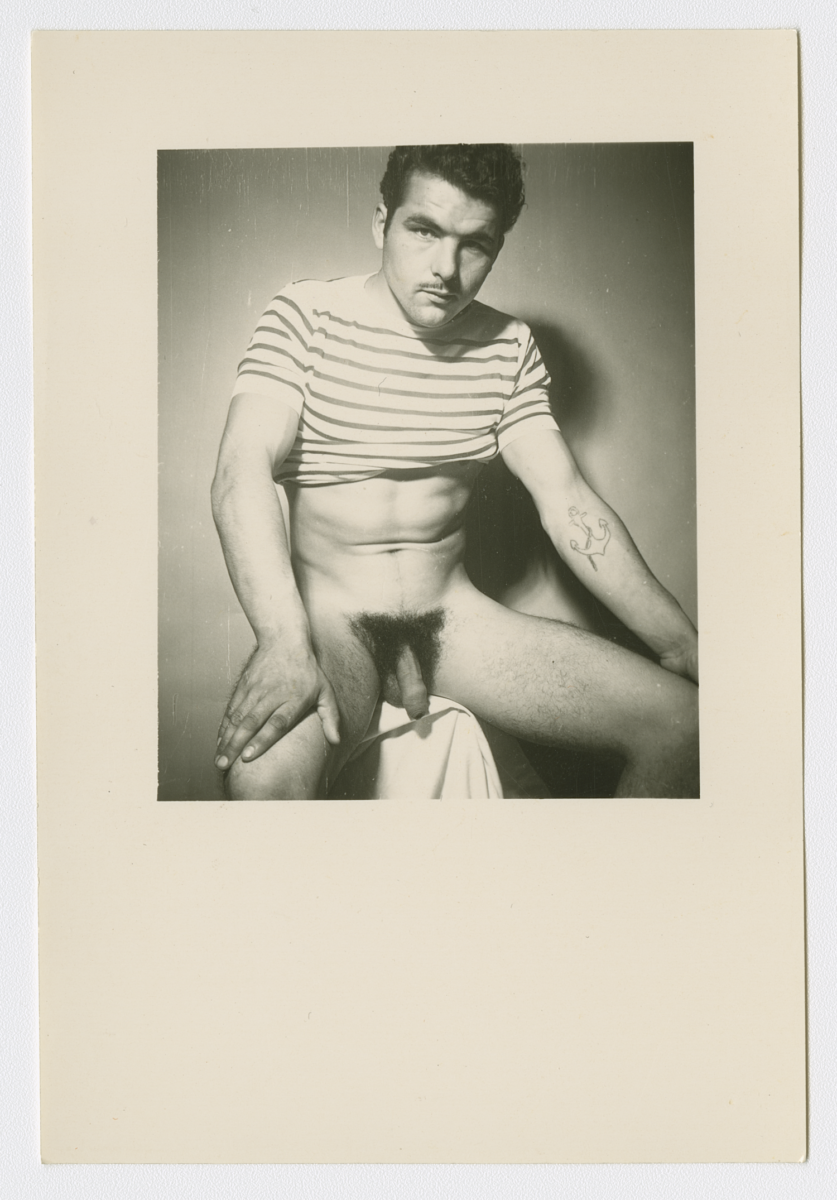

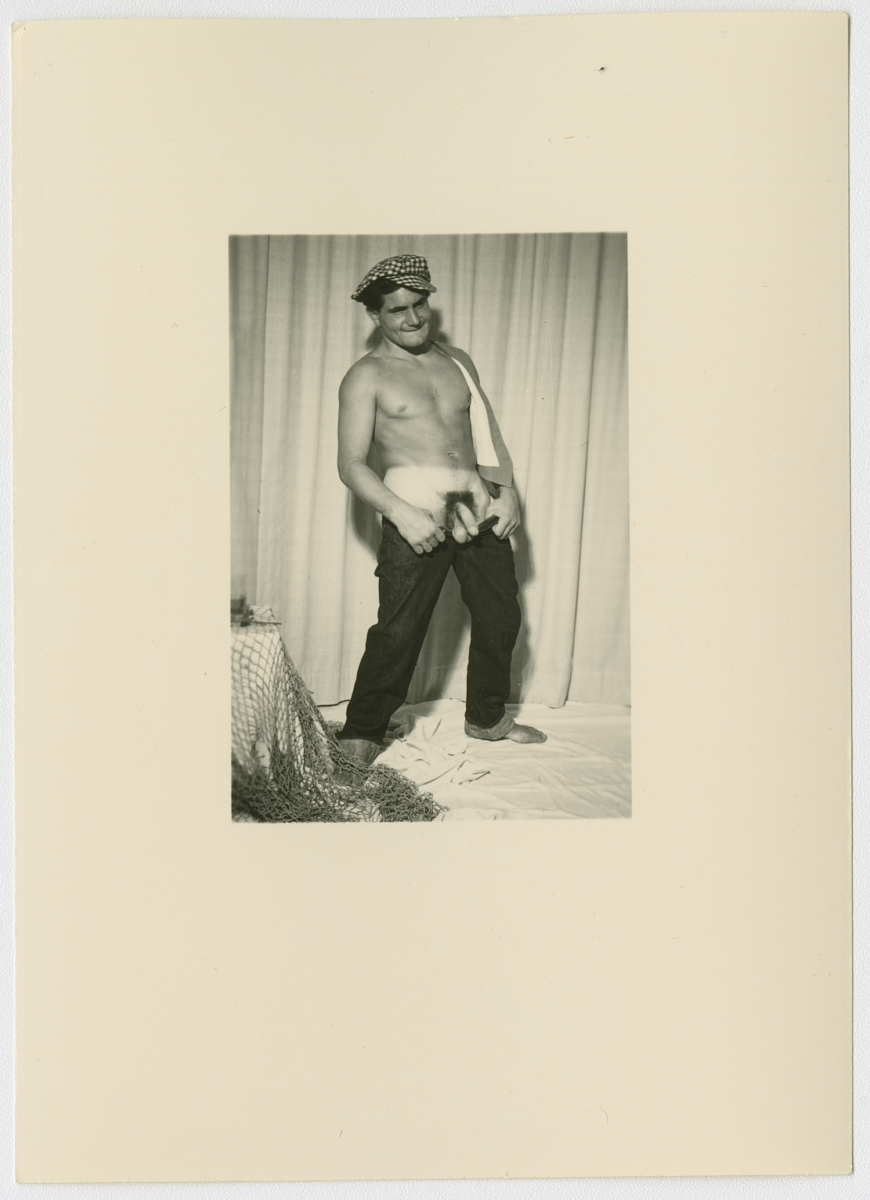

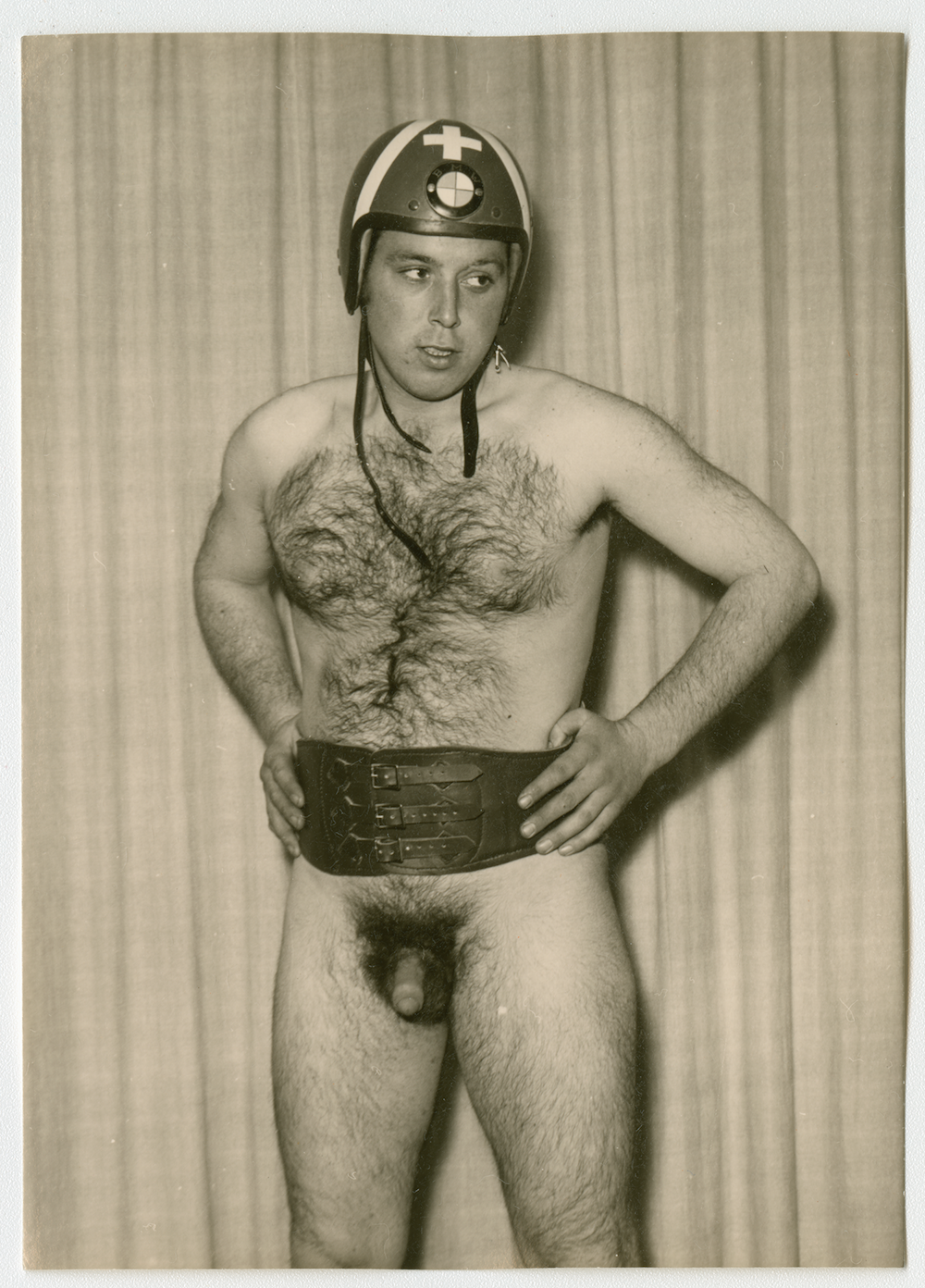

Perhaps it takes an “amateur” to capture the vibrancy of sex, pleasure and even artistry that Karlheinz Weinberger managed to imbue in each of his images. Unflinchingly erotic but always tender, his work denotes a sense of intimacy between photographer and photographed that few achieve.

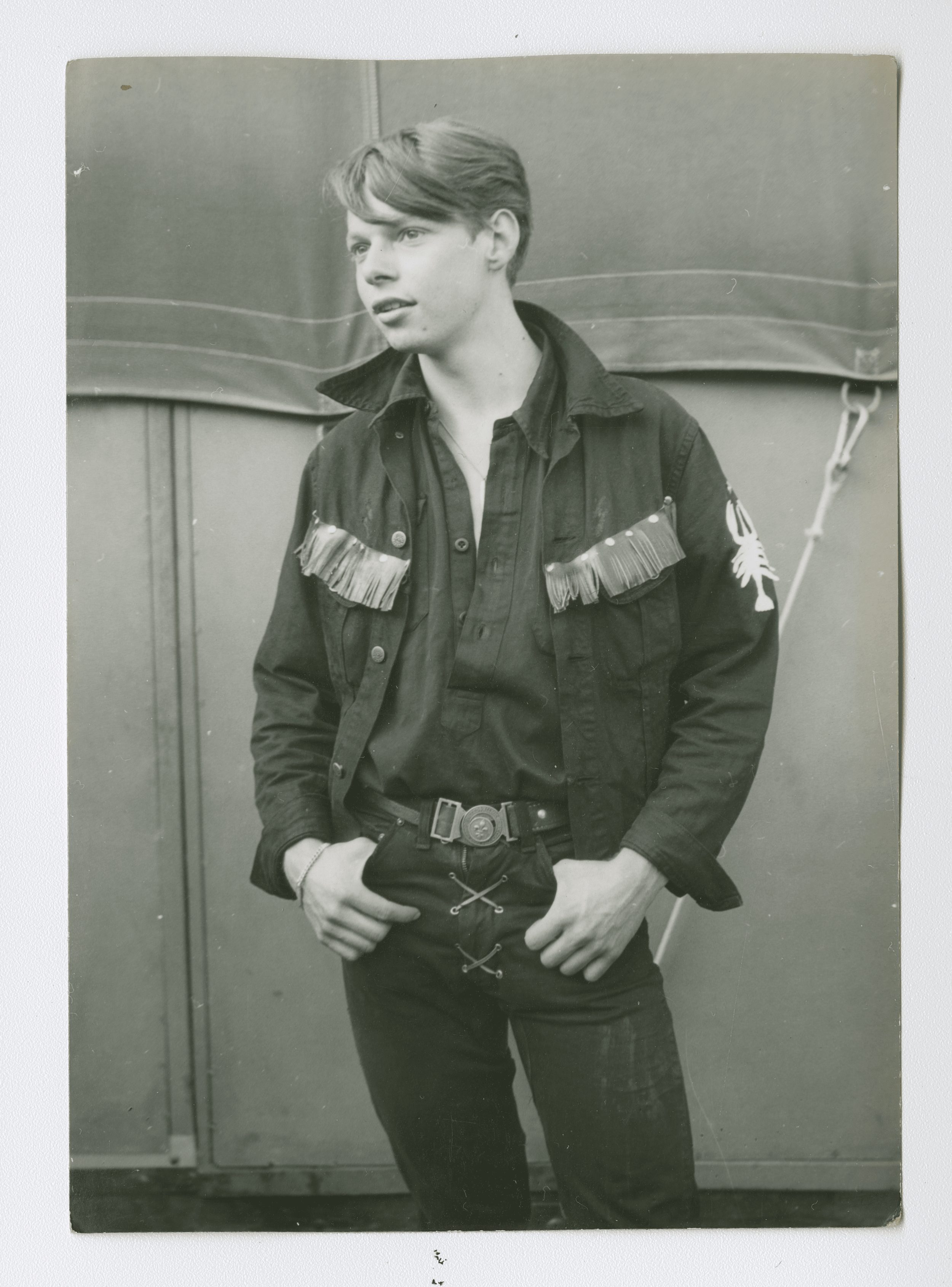

A new book published by The Song Cave (and its accompanying exhibition at New York’s Situation gallery) brings together previously unseen works by Weinberger, which focus on construction workers and the Swiss “rebels” that he is best known for. These “rebels” were more precisely the “Halbstarke”, a loosely organised group of young Swiss men who used to spend their time in the late 1950s and 60s sampling the wares of local carnivals, camping, hanging out and generally having quite a good time. Weinberger captured them out in the streets, as well as in more formalised studio portraiture.

- Portraits, Zurich c. mid to late 1950’s © Karlheinz Weinberger Stiftung, Zurich, Courtesy of Artist Resources Management, New York

“Unflinchingly erotic but always tender, his work denotes a sense of intimacy between photographer and photographed that few achieve”

That his sitters were outsiders, many of them choosing to live beyond the mainstream, is befitting of Weinberger’s own stance, both in his own lifestyle and within the artistic canon. Born in 1921 in Zurich, he did not train as a professional photographer. Instead, he worked as a warehouse stock manager, and the “studio” shots were in fact shot in a makeshift setup in the apartment that he shared with his mother.

This domestic setup might explain a modicum of that sense of intimacy, but far from all of it: this was clearly a man who knew exactly how to put his subjects at ease. He also knew how to pick them: each gesture, each gentle eyebrow raise or muscle clench is beautifully poised. You get the impression that everyone here was enjoying themselves, and with that comes a rare intimation of self-conscious irony that adds an extra sparkle to Weinberger’s work.

This is the male gaze—a testosterone loaded affair—but not as we most often see it: his artistic vision is unashamedly camp (a testament to Weinberger’s artistic convictions, and those of his models). Switzerland was undeniably progressive compared to most countries when it came to gay rights, with same sex relationships legalised in the 1940s and Zurich becoming an important European gay capital in that decade. But it wasn’t until the early 70s, post-Stonewall, that the LGBT movement really began to take off. It was also in the 1970s that many other legal forms of discrimination against gay people were officially abolished, such as equalising the age of consent, and the elimination of different tax laws for homosexual and heterosexual members of the army.

One of the key tenets of Zurich’s progressive stance when it came to the gay scene was the magazine Der Kreis, a Swiss gay publication that ran from 1932 to 1967 and was distributed to an international readership. It was in these pages that Weinberger’s work was published from 1943 until it was closed. These commissions included his now iconic images of sportsmen and bikers, which were shown under Weinberger’s artistic pseudonym “Jim.” His best known works are probably those he went on to shoot in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, during which time he turned his lens on the nascent rock and roll scene in Switzerland’s youth culture.

The images in this book, however, are simply titled Karlheinz Weinberger: Photographs Together & Alone, and comprise 200 never-before-published prints that were only rediscovered in 2017. The emphasis here feels more personal than that of his more famous works, with the images skewed towards those shot at home with models that included builders, street vendors, bicycle messengers and other usually un-photographed men. The shots veer from outright flirtation with the camera to wry, quietly gleeful imitations of classic art-historical poses.

“The shots veer from outright flirtation with the camera to wry, quietly gleeful imitations of classic art-historical poses”

At this point in his career Weinberger was still not a “professional” photographer, at least in the sense that his art was not how he earned a living. He was a resolute outsider, and remained forever reluctant to exhibit his works; his first comprehensive show wasn’t staged until 2000, six years before he died. But these images show that his own “outsider” sensibility was perhaps lessening: the art direction, the obvious confidence he could instil in his sitters implies a man who both knew what he was doing. Ultimately, they hint at an awareness that his imagery was both beautiful and important.

Karlheinz Weinberger: Photographs Together & Alone

Edited by Ben Estes. Introduction by Collier Schorr. Published by The Song Cave.

VISIT WEBSITE