Writer Dalya Benor speaks with artists from Venice Glass Week, a full week dedicated to an international showcase of glass with artists all under 35 years old.

What’s hot, cool, and sees right through you? It’s glass. That oozing, brittle, painfully-delicate material that makes up so much of our day-to-day life, we often take it for granted. Yet, for a handful of young artists, glass contains a world of possibilities — breaking the bounds of centuries-old traditions in order to create something elevated to works of art.

While glass the material can be traced back almost 4,000 years ago to Ancient Egypt, Italian glassmaking in the tradition of Murano began around 1291. During that time, glass was seen as such a valuable and secretive process that the Italian government ordered glassmakers and their furnaces to move from Venice to the island to keep the secrets highly protected. The traditions within Murano glassmaking are rigorous and time-tested — in many furnaces, an apprentice can work for 30 or 40 years before he can move up the ranks to become a “master.” As an example, one of the oldest furnaces on the island, Barovier&Toso, started in 1295 and is still operating today, creating some of the most intricate and refined decorative objects.

In the larger cultural context, glass has always tiptoed the line between the design and art worlds, causing confusion as to which one it should call home. In 1912, glass began to be recognized as an artform, noted with its inclusion in the Venice Biennale. However, the medium disappeared from the Biennale in 1972, leading organizations like Le Stanze Del Vetro in Venice to devote time and resources to restore the art of glass to its historical splendor.

Now, a group of contemporary young glassmakers are finding new ways to use the material in conceptually-inventive ways, breaking with tradition to create pieces that blend ancient craftsmanship with innovation in design. Thanks to The Venice Glass Week, an international showcase of glass founded in 2017, a number of artists under the age of 35 continue to breathe new life into the material.

Below, we catch up with artists Tessa Sakhi, Clara Schweers and Linda Tidenberg.

1. Tessa Sakhi:

As a trained architect, how did you get started working in glass?

I began working with glass in 2016 when I first visited my friend Marcantonio Brandolini d’Adda in Venice, who had taken over his mother’s company, Laguna B. I went to their palazzo and saw all the creations by his mother, Marie, as well as the Murano glass collection of his grandmother. We visited a factory in Murano together, and I immediately fell in love with the art of glassmaking—the transformative journey of glass from liquid fire to solid glass got my “heart on fire.”

What’s the biggest surprise or learning curve you’ve had working with glass?

Initially, working with glass was very challenging for me because I couldn’t control the medium as I’m used to with others. First, I’m relying on the hands of glassblowers, who are in control of the process. Additionally, we work without molds, making it difficult to “perfect” the object. Over time, though, I’ve learned to embrace the unknown and uncertainty. This experience has taught me how to let go, embrace surprises and accidents, and work with them—a transformative journey both in my work and within myself in life.

Can you describe the concept behind your piece you exhibited at Venice Glass Week?

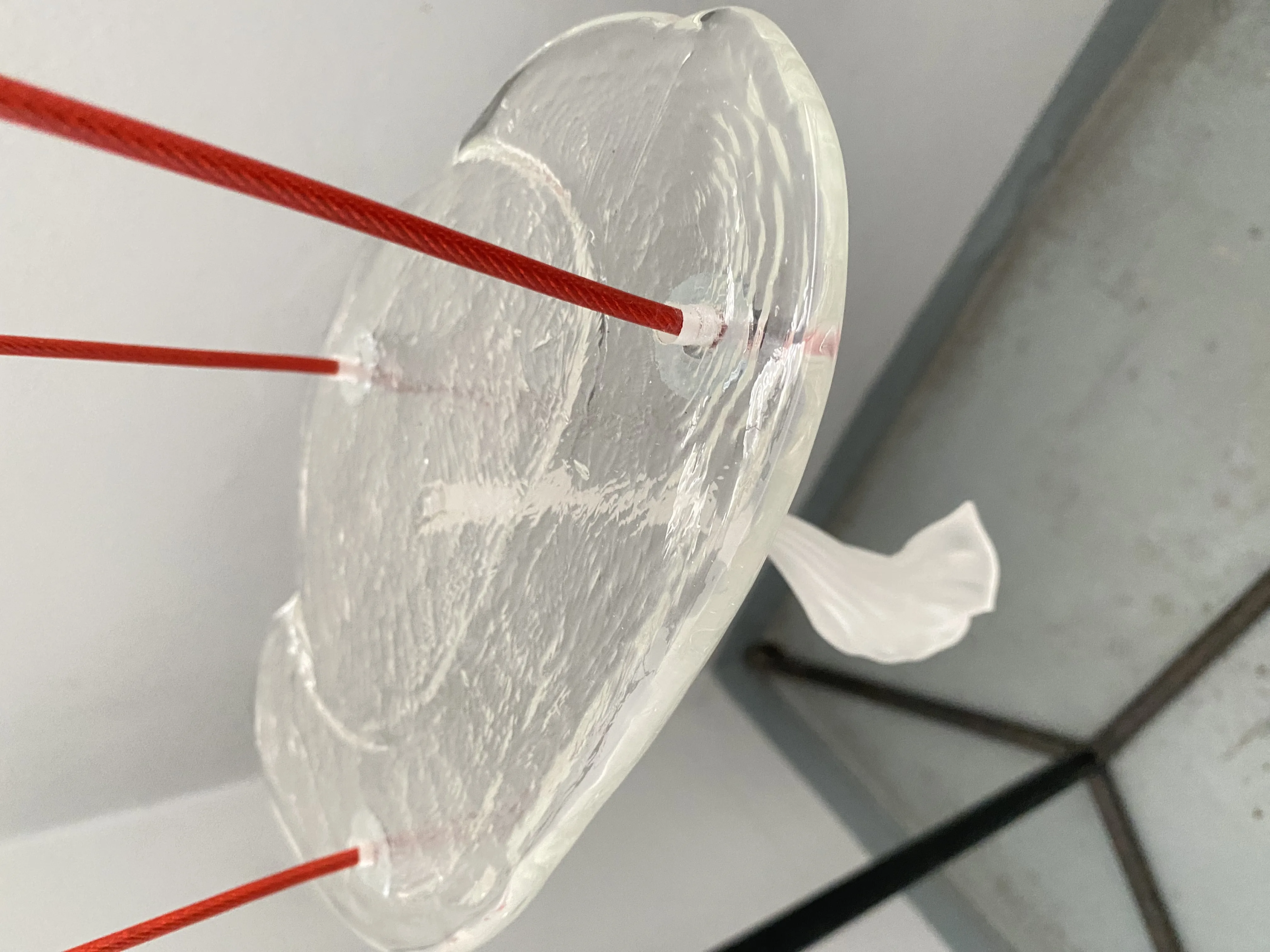

Since 2016, I have been engaged in innovative collaborations with Venetian glassblowers on the island of Murano, trying to push the boundaries of glass textures through experimental techniques. Sourcing various types of discarded metals from factories in the Veneto region, I infuse them into the glass at varying states and temperatures. The pieces evolve throughout the production process inspiring me to explore the unknown, embrace the unpredictable alchemy of raw materials blending together, and adapt to the surprises and accidents that arise along the way. Each sculpture, uniquely crafted and skillfully mouth-blown by master glassblower Fabiano Amadi, stimulates a sense of curiosity and touch to the viewers and invites them to explore cosmic glass.

What’s exciting to you about working in glass at this current time?

Crafted at the heart of Murano’s glassmaking tradition, my work reflects a dialogue between the Venetian lagoon where I live and my Lebanese cultural heritage, drawing connections back to the Phoenicians and their ancient glassmaking techniques across the Mediterranean since 1500-300 BC. This cross-cultural exploration highlights my commitment to merge historical craftsmanship with contemporary innovation, which is my works’ ethos.

2. Clara Sofia Schweers:

What has your journey as an artist been like?

My journey as an artist is tied to my background in Industrial Design and my experience at the Design Academy Eindhoven, where I graduated with a Masters in Contextual Design in 2022. Neither of these disciplines focused on a single medium, which I found incredibly freeing. It allowed me to explore a wide range of techniques, from digital to analog methods of expression.

What interests you about glass specifically?

I like to think of glass as a kind of fourth wall. It acts as a visual and special effect, using various methods, techniques, and processes to distort the viewer’s perception of what can be achieved through hands-on craftsmanship. This idea of the fourth wall also ties into the conceptual core of my practice, where I explore the duality and feedback loop between digital and physical worlds. Glass, in this sense, becomes a medium that bridges these spaces and challenges how we interact with them. As a screen—whether in laptops or phones—glass is everywhere. Despite being physically non-conductive, glass somehow becomes a carrier for transmitting digital gestures and ways of behavior into my body.

While using and studying traditional techniques in glass to create visual effects, glass ties my practice to a very digital culture. Through its duality, glass oscillates between the traditional and the emerging, creating a special connection between its organic and to me also digital qualities.

What have you learned from working with glass?

Glass offers me something unique that other mediums don’t—it feels very personal and immediate, especially when working with techniques like lampworking. With the burner, I can shape the material quickly, and it responds fluidly to my movements, which allows for a direct, hands-on approach. However, glass also teaches patience, especially when using the kiln, where the results are always a bit of a surprise. This mix of control and unpredictability keeps me engaged.

The material itself is a contradiction, embodying both durability and fragility. Working with glass means accepting that things will break, which is a thrilling but humbling process. This balance resonates with me, as it requires a certain mental and emotional durability as well.

And of course I also find it fascinating to juxtapose new media techniques with glass. The combination of hands-on craftsmanship with digital, high-tech aesthetics creates an interesting tension that continues in my work and different projects.

How did you develop your piece for The Venice Glass Week?

The Vein Mirror is a piece that plays with the illusion of being metallic and virtual, but it’s actually crafted from glass and silver. Its web-like, netted appearance reflects my main approach of distorting, combining, and mirroring computer-generated figures into abstract objects. By fusing glass sheets into intricate patterns, I’m able to form meshes and mirrors that have this organic, fluid quality.

The physical properties of glass allow me to create smooth, rounded strings, which I then hand-polish and silver. This transforms the piece into a reflective object that interacts with its environment, creating a sense of movement as viewers move around it. It’s fascinating to witness how analog effects give the mirror a very dynamic and also unexpected presence.

Conceptually, the piece is rooted between organic and digital qualities and perhaps also visualized this idea for me first hand. The piece becomes a medium that captures fleeting moments, while adding layers of high-definition and distortion to its surroundings.

What other artists inspire you?

Laure Prouvost, Daniel Dewar & Grégory Gicquel, Dominique Fung, Silvia Levenson, Rene Lalique.

Where do you look for references or influences for your work?

Film and digital storytelling aesthetics play a crucial role in my work. Rather than seeking existing references, I aim to create my own. Since 2022, I’ve been exploring digital characters and their motion libraries, commonly used in gaming, which have become vital elements in my practice. Through the distortion of these bodies, I compose my visual language. Many of my works are arrangements of distorted, combined, and mirrored stock characters, translated into tangible objects and installations.

Linda Sofia Tidenberg:

Where did you learn to work with glass? What was your training like?

I’m still actively learning and training. I’m currently a glassblowing student, studying to become a glass artisan. My school is located in the beautiful glass village in Nuutajärvi, Finland, at Tavastia Vocational College. We focus on learning basic techniques, working as a team, mould blowing and making tons and tons of repetitions. We also have a workshop program where we work with design students on their own molds and projects, which helps prepare us for working with clients and doing custom work.

What possibilities does glass offer you that other mediums might not?

Glass teaches you. You have to learn to be patient, to be tender and learn to accept that at the beginning you suck. It strengthens your resilience more than anything else. I have always been very much like “jos ei nätisti niin väkisin” which translates to “if something doesn’t work out nicely it will by force.” But with glass, that approach doesn’t work. I was struggling a lot at the beginning because I had to learn how to handle things gently. You have to give glass your full attention. Working with glass is like dancing with your loved one — every small touch and gesture guides you forward together. Glass has taught me patience, kindness, and boosted my confidence — just like a good partner would.

What was the process for your piece in The Venice Glass Week exhibition?

My installation is an evolution of my earlier work, 51 Days, which explores the embrace of the polar night in the North, where autumn’s final wild blooms surrender to nature’s whims. The name comes from kaamos— polar night, a time in winter when the sun doesn’t rise for 51 days. I originally created these frosty flowers for my first exam, just four months into working with glass. When I saw the open call for the exhibition, I knew I had to give it a go. But I realized I couldn’t just present the flowers alone— I had to get into my storyline and find a way to present them in a light that would give them the recognition what our resilient northern flowers deserve. I also wanted to pay tribute to Nuutajärvi, the place where I found my calling. I’ve always had a unique way of seeing the world, and drawing inspiration from Finnish animistic mythology and storytelling, I aimed to reflect that in this piece.

What excites you about working with glass in the current moment?

I’m thrilled about the attention glassmaking is receiving, especially with UNESCO recognizing it and bringing it into the spotlight in Finland. We have so much talent here, and I believe studio glass deserves more appreciation. It’s exciting to be working in this field at a time when more young artists are getting involved, bringing diversity and depth to our cultural heritage.

Why do you think there’s a renaissance in glass happening currently?

I think it’s because we have so much new talent coming in, and artists are using glass in more expressive and artistic ways, rather than just focusing on the technical aspects. There’s a lot of innovation happening, and people are pushing the boundaries of what glass can do. It’s exciting to see more artists incorporating personal storytelling and unique concepts into their glasswork. Plus, I think there’s a renewed appreciation for craftsmanship and handmade art, which is bringing more attention to the medium.

Words by Dalya Benor