Last week, we looked at the London MFA shows through the lens of political conflict and climate change. Another exciting strand of work was also apparent throughout the graduate shows—one that contemplated authenticity, truth and identity, particularly within the body.

If you were to sneak under the daunting staircase at the front of the Royal Academy, past the crowds that descended for the summer exhibition, you would have come across a long hallway lined with statues of chiselled Greek and Roman men and anatomical models showing off their muscles. Keep walking and you would notice that one of the larger statues was circled by voices whispering descriptions of female bodily processes in visceral detail—an installation by Matilda Moors that rubbed up against the cold hard stone of Hercules, bringing attention to the more alive, less picturesque side of the human form.

Elsewhere, female sexualities are explored with humour in Amy Steel’s acidic, surreal paintings at the Slade. In one, a naked woman with a bunny’s head exudes confidence, sitting open-legged and addressing viewers with a tilted head; in another, women ride giant pink boobs into the sunset.

These boobs are a recurring motif, and are echoed in her painting A Long Last Look, in which a huge camera and three trench-coated men stare down at a conical mound, presumably discussing whether it lives up to their ideal size and shape. The women, however, couldn’t care less, and Steel’s use of hot pinks and fluorescent oranges intensify their frank, funny and woman-centred eroticism.

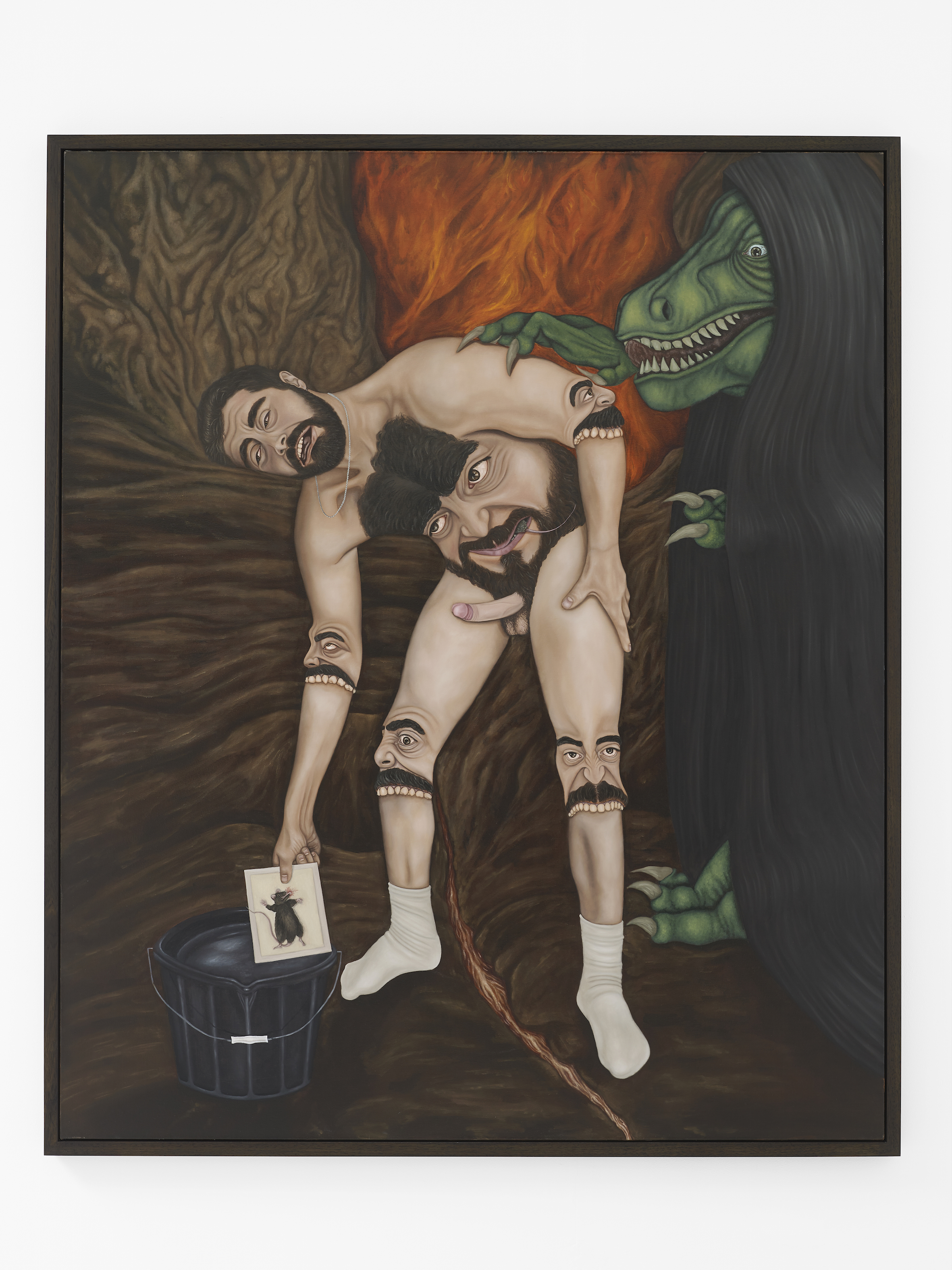

Glen Pudvine, Dying, 2019

Sexuality, along with notions of white masculinity, is picked apart by Glen Pudvine’s self-portraits at the RA Schools, which depict the artist (naked except for white socks) wandering through some kind of Eden, engaging in an assortment of activities and shown in states of arousal with a dinosaur accomplice.

Pudvine renders his own body in the lifeless tones of international gothic paintings, with bloodshot eyes and rubbery grimaces. Sometimes this skin suit becomes all face, sometimes it is removed entirely from the body and held up like something nasty. The dinosaur remains lurking, at once seeming to be taunting and protecting him, binding humour and horror into the work.

These anxieties surrounding identity are explored through flat-packed bodies in Shinuk Suh’s kinetic installation at the Slade. Wobbly rubber limbs and items of clothing peel away from their wooden frame with pathos, and cartoonish white hands awkwardly stroke flabby hanging bodies.

Made in South Korea (Ideological State Apparatus) drips with a tragic humour, whilst also speaking of systems of control—the hands perform the most movement in the piece, making contact with the surrounding elements gently but firmly, attempting to guide, signal or restrain. People are literally hung out to dry—as if the self that they’d managed to piece together that morning had been interrogated and found to be not quite up to scratch.

Control and authenticity are cleanly and coolly questioned in Ellie Wyatt’s work at the Royal College of Art, which probes “textual languages frequently associated with truth-telling”. It unfolds across the wall like an exploded textbook, complete with muted, institutional colours and reference photographs.

Towards the centre sits an image of a hand pointing a scalpel that glints with a threatening acrylic sparkle, a reminder of the subjective cut and paste process involved in forming narratives that we often absorb as objective truths, particularly in academia. A Well Trained Eye guides us with symbols, rings, arrows, but to what, exactly? Ambiguous fragments of language let us know that there are no facts or singular narratives to be found here.

- Gabriella Davies, Dad, Dancing, 2019

The question of truth and authenticity is pondered in terms of personal identity in a moving film by Gabriella Davies (RCA) titled Dad, Dancing. In a short but sweet three minutes, Davies celebrates her father’s tendency to let loose when given free reign over the jukebox in their local pub, and uses this a ground from which to discuss his reaction to her transitioning and the importance of choice in the question of who we really are.

Grainy footage of her dad having what looks like the time of his life coupled with Davies’s contemplative narration form a tender portrait of familial love, and music as a refuge from a world that seems to constantly seek to pigeon-hole.

The power of music, or really listening, is also demonstrated in the work of Demelza Toy Toy (RCA), whose installation appears like a set up for band practice: guitars, amps, record players and microphones strewn across the floor. Instead of records playing on the turntables, house plants rotate. A large portrait of Toy Toy hangs on the wall, in which she clutches one of her plant and turntable instruments and concentrates her gaze into the middle distance.

A performance by the artist got viewers to activate the work according to scores she had constructed. It feels that she is compelling us to listen deeper, not just to music but to every living thing and every part of the world around us, along with what’s going on inside ourselves—perhaps we will discover some hidden sonic truths?