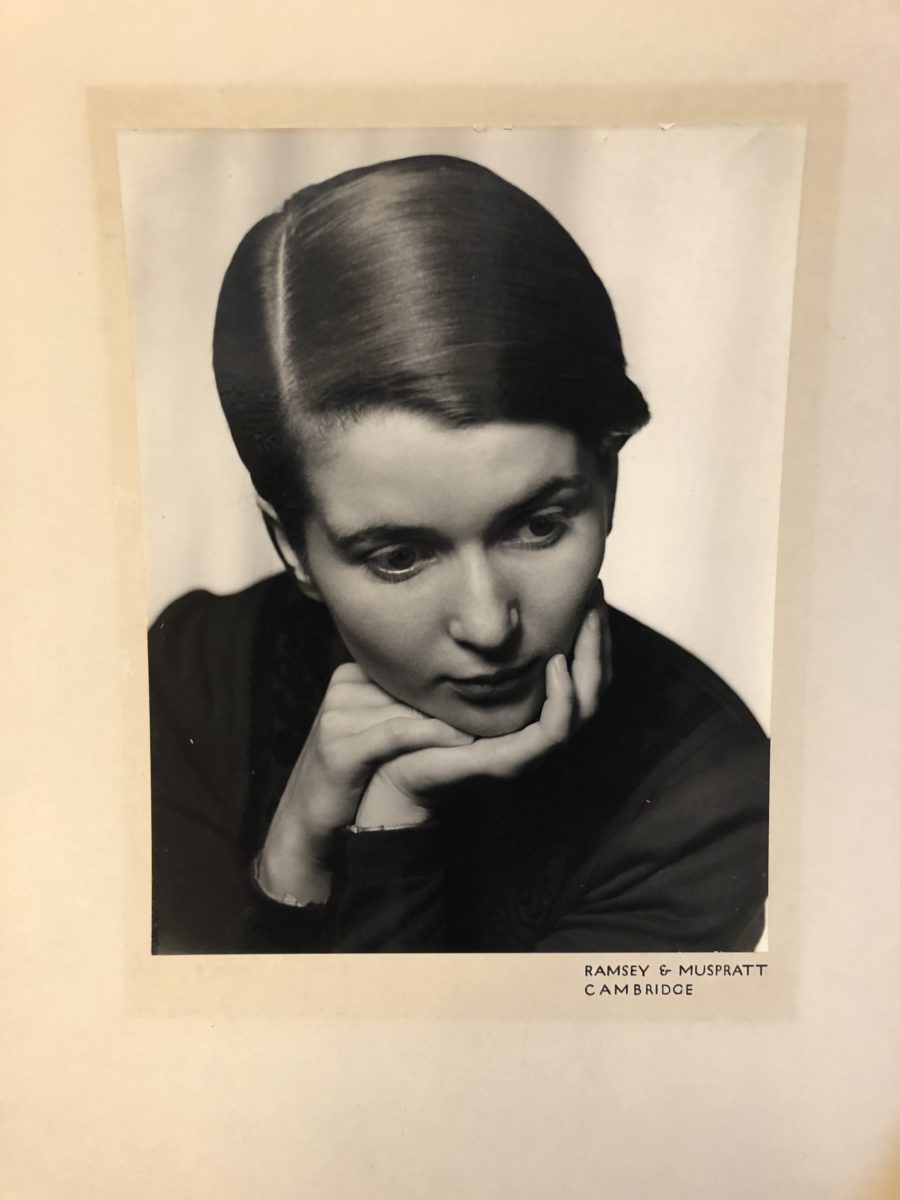

It is no secret that women’s work often goes unrecognised, whether it be labouring in the home, fulfilling a traditionally “male” occupation without fanfare, or having creative ingenuity overlooked. For Helen Muspratt, it was all of the above. The pioneering twentieth-century photographer was just as comfortable producing experimental portraits of the artistic elite as she was documenting life in the Soviet Union and Welsh coalfields. She was also a dedicated communist, the main breadwinner for a family of five, and ran a commercially successful photographic studio with her artistic partner Lettice Ramsey. Yet her legacy remains obscure, even when peers such as Lee Miller have finally been getting their dues in recent years.

Hopefully this will all begin to change, following a gift of over 2,000 original prints and even more surviving negatives to the Bodleian Libraries

in Oxford. This major archive forms the basis of an exhibition at the libraries, curated by her daughter Jessica Sutcliffe. Such personal insight contextualises a practice that was not easily defined.

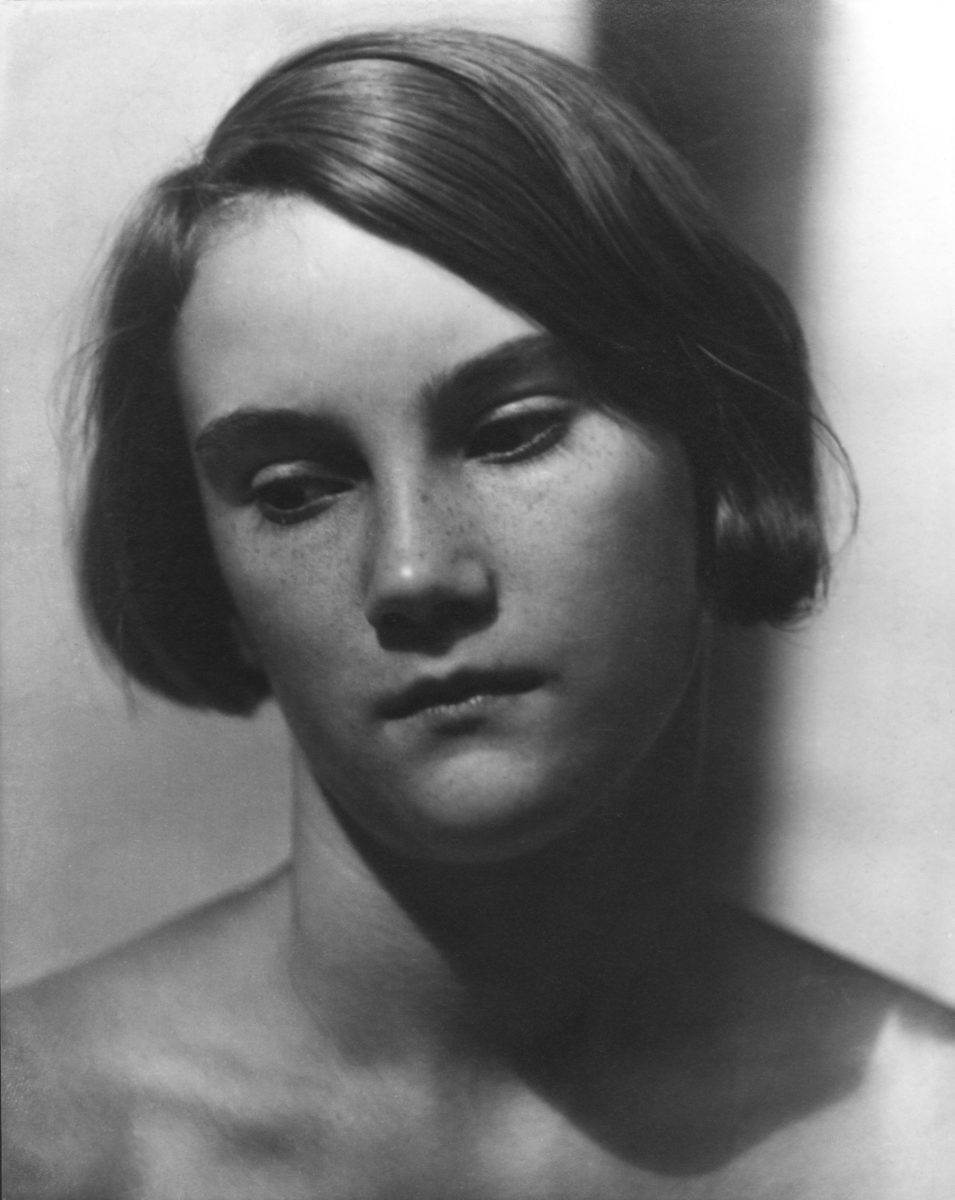

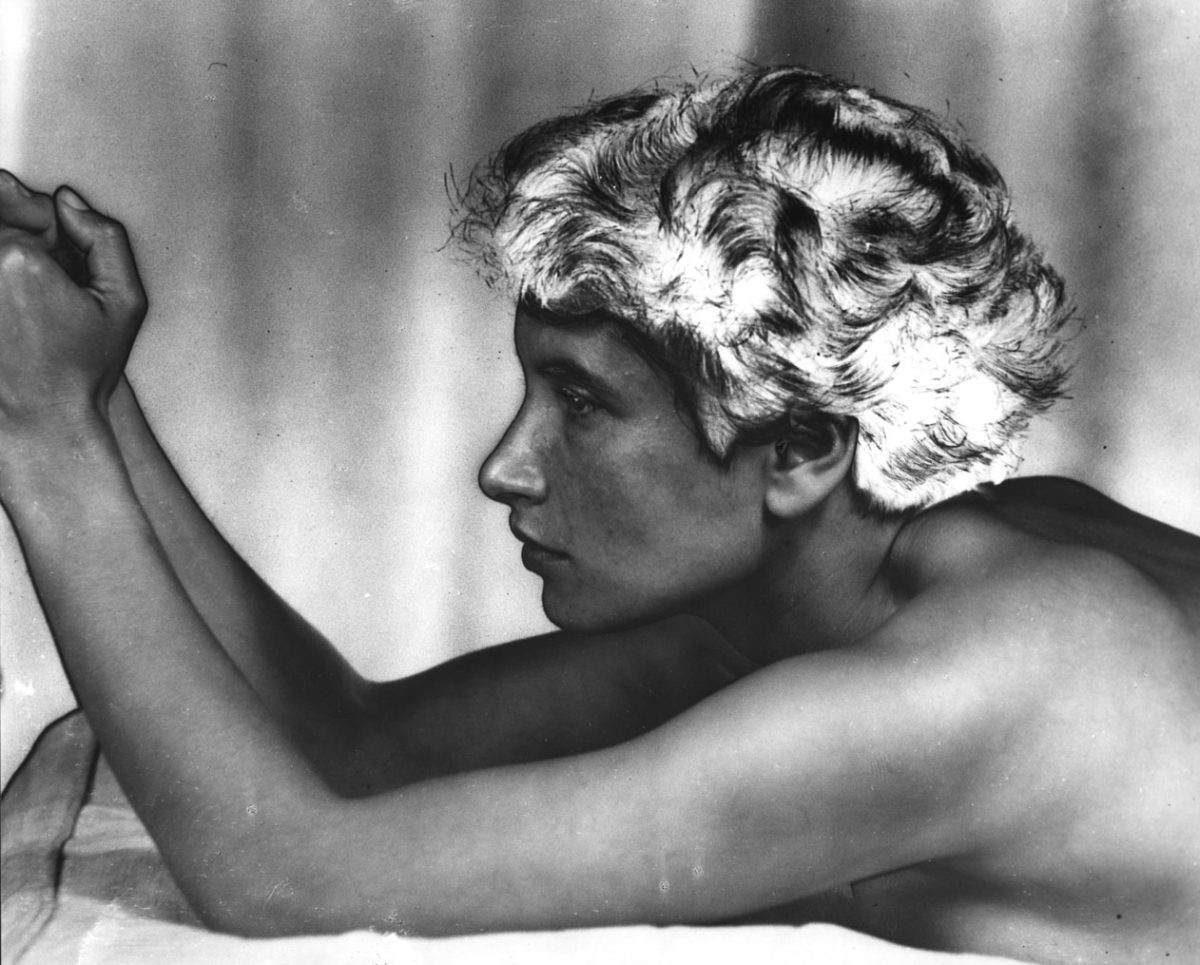

One would be forgiven for thinking that journalistic shots of Russian farmers have little to do with carefully conceived studio portraiture, but Muspratt’s keen eye and intimate approach was part of a wider modern movement that saw the camera not merely as an instrument with which to record reality, but an important storytelling device that could shape and mould perceptions through light, framing and composition.

“With a focus on clean lines, clarity, but above all naturalism, she was able to capture some of the greatest artists and thinkers of the time”

Muspratt also had a rather egalitarian approach to producing images. For one, most of the work made with Ramsey in their studios in Swanage and Oxford were not clearly signed or attributed. Moreover, the pair understood (and gave space for) the challenges of parenthood at a time when the idea of being a creative professional and a mother was practically unheard of.

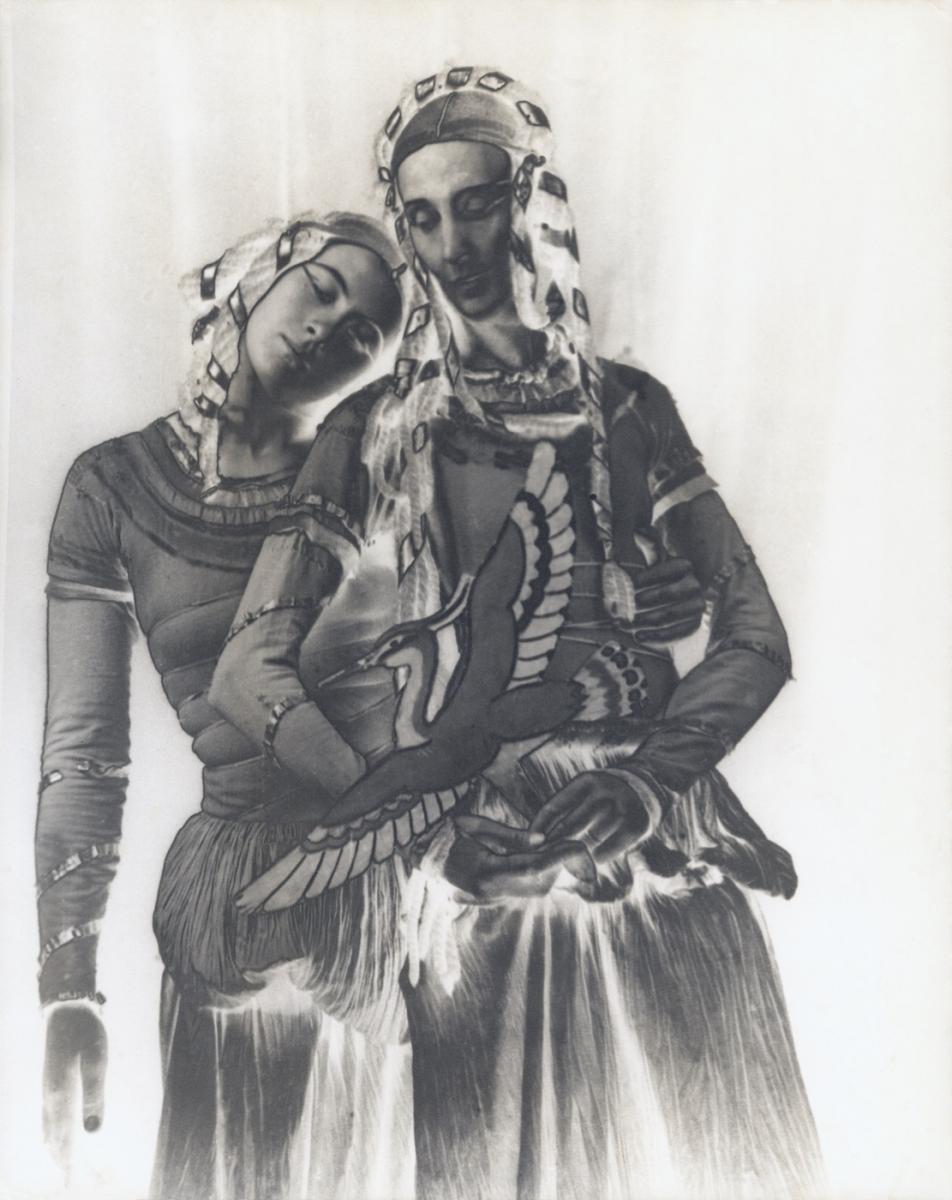

In her more experimental projects, too, Muspratt sought the artistic input of her sitters, as seen in the fantastical costuming worn by Hilda and Mary Spencer Watson

. The mother-and-daughter duo were known for putting on elaborate performances at their home theatre in Dunshay Manor

, Dorset, where they entertained an array of artists, musicians and performers. The result is an alluring and surreal image that seems both ancient and futuristic, thanks to Muspratt’s use of solarisation, a new and exciting technique of the moment, popularised by Man Ray. The treatment sees tonality is reversed, giving the effect of an ethereal glow.

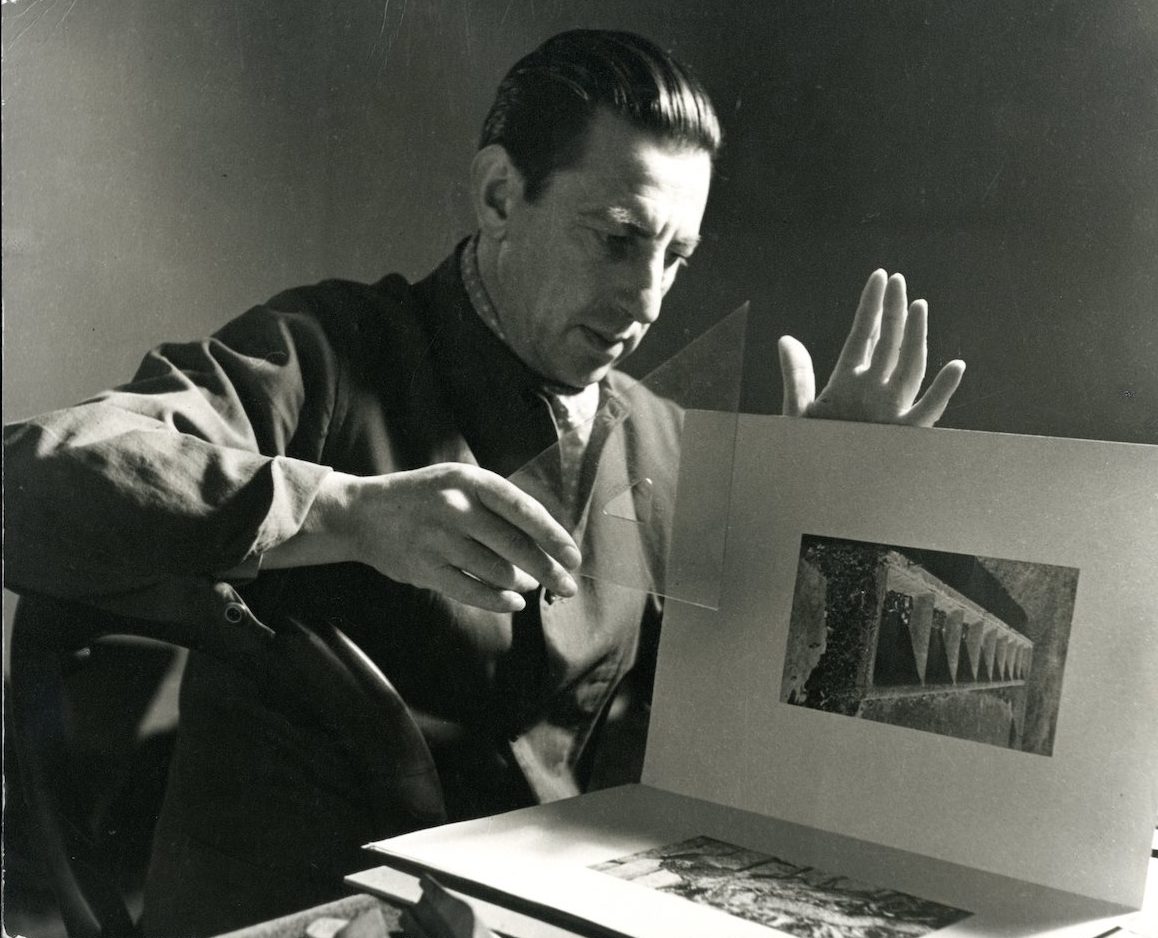

Though these experiments are some of the photographer’s best-known work, she also produced formidable formal portraits. With a focus on clean lines, clarity, but above all naturalism, she was able to capture some of the greatest artists and thinkers of the time in unguarded poses. Her image of Paul Nash, for example, is an impressive exercise in spatial geometry, yet the man in question remains the central focus. Although the wonderful result has been frequently used in exhibitions and books, Nash was less convinced at the time, writing to his wife: “I enclose some pretty grim photographs; do I really look like that?” Proving that beauty is always in the eye of the beholder.