Through symbolism, sound, and architecture, Pol Taburet’s latest exhibition turns Madrid’s Pabellón de los Hexágonos into a space where the spectral and the sacred meet; a liminal realm of shifting forms and pure silence.

Nestled west of central Madrid in the city’s largest urban park, the Pabellón des los Hexágonos is exemplary of mid-20th century Spanish architectural prowess. The brainchild of José Antonio Corrales and Ramón Vázquez Molezún, the structure was primarily erected for, and won first prize at, the 1958 Brussels Universal Expo. Dismantled and reconstructed in its current home within the Casa de Campo exhibition ground, the now-iconic structure is activated by Pol Taburet’s Oh, If Only I Could Listen – the Paris-based artist’s first Spanish show, bringing together a series of new works spanning drawing, lithography, writing, painting, and sound.

Running from March 5th until April 20th, the show forms part of a lineage of nomadic exhibitions staged by the Fundación Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Madrid, in furtherance of the organisation’s mission to bring art and culture to unexpected spaces. Curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, the exhibition’s framing of hybrid spaces and bodies in limbo, of interspecies entities and supranatural forms, finds harmony with the Pabellón’s distinct angularity and contemplative air.

Immersing himself in the city’s landscape in order to respond to the architecture of the exhibition space, Pol spent time in Madrid’s Museo Nacional del Prado – Spain’s largest national museum, within whose collection the hundreds of works by Goya make him the most represented artist. Just as Goya’s paintings are marked for their narrative capacity – their ability to capture then-contemporary upheavals and happenings with clarity and nuance – so too do Pol’s paintings pass astute commentary on contemporary dynamics of power and violence, and the existential. The exhibition constitutes a dialogue between the Spanish art historical canon and Pol’s own visual references; an acknowledgment of the symbolic cycles that reverberate across time.

The foyer is home to Pol’s first foray into lithography: eight grey-scale, comparatively diminutive prints produced in the historical Imprenta Municipal-Artes del Libro. Alongside those presented within the Pabéllon, additional editions by Pol are shown coterminously at the Imprenta under the aegis of Atelier Pol Taburet. In the foyer too, we encounter a sound installation: a collection of extra-musical sounds, lofty voices and soaring trumpets, concentrated in the anteroom. The soundscape was composed with recourse to the building itself; beginning with the sound of metal and rocks, it continues with airy voices, dislocated whispers that mirror the deflection of utterances off the Pabéllon’s angled walls. For Pol, the localisation of the soundscape constitutes a preparatory cleanse – the public is “washed in the sound and they become clean in the show, in the silence.” He invites us to encounter the works from a place of purity, devoid of judgement; “to come in a very serene way, and to wash all these fake narratives [away].”

When queried about the title for the exhibition, Pol admits that it followed the work’s production. This manner of naming is familiar for the artist, whose endowment of nominations hinges upon the sensibility revealed upon the painting’s completion. That’s part of the process for him, “to decide which kind of sound the painting is going to make.” Renowned for the production of arguably “loud” paintings – works abundant with colour, that overtly balance ribaldry and morbidity – the exhibition deviates from Pol’s prior oeuvre, insofar as its central idea was to make the paintings silent. To walk through the rest of the exhibition is to be shrouded in this hush, a quietude drawn upon as a condition Pol imagines typifies limbo: “In my imagination of limbo, it would be something like a waiting room between paradise and hell…very silent, and also curved.” A characteristic of curvature is its elusiveness; within his paintings, Pol plays with the balance of sharp lines and rounded forms to foreground this sense of transition.

Entering the main exhibition space feels purging, purifying; an imposition of sanctity affirmed by the chapel-like essence of the elongated chamber. The central shape of the hexagon is repeated as the sides oscillate across four alcoves and corresponding protrusions, each of the former curving around a six-sided dais. Within each recess, Pol’s paintings are affixed to the site’s structural columns, suspended in space in a manner that echoes his subjects’ affinity for gravity-defiance. Almost instinctively, the visitor traverses the space in a singular, processional movement, in the manner one might descend a church aisle during communion.

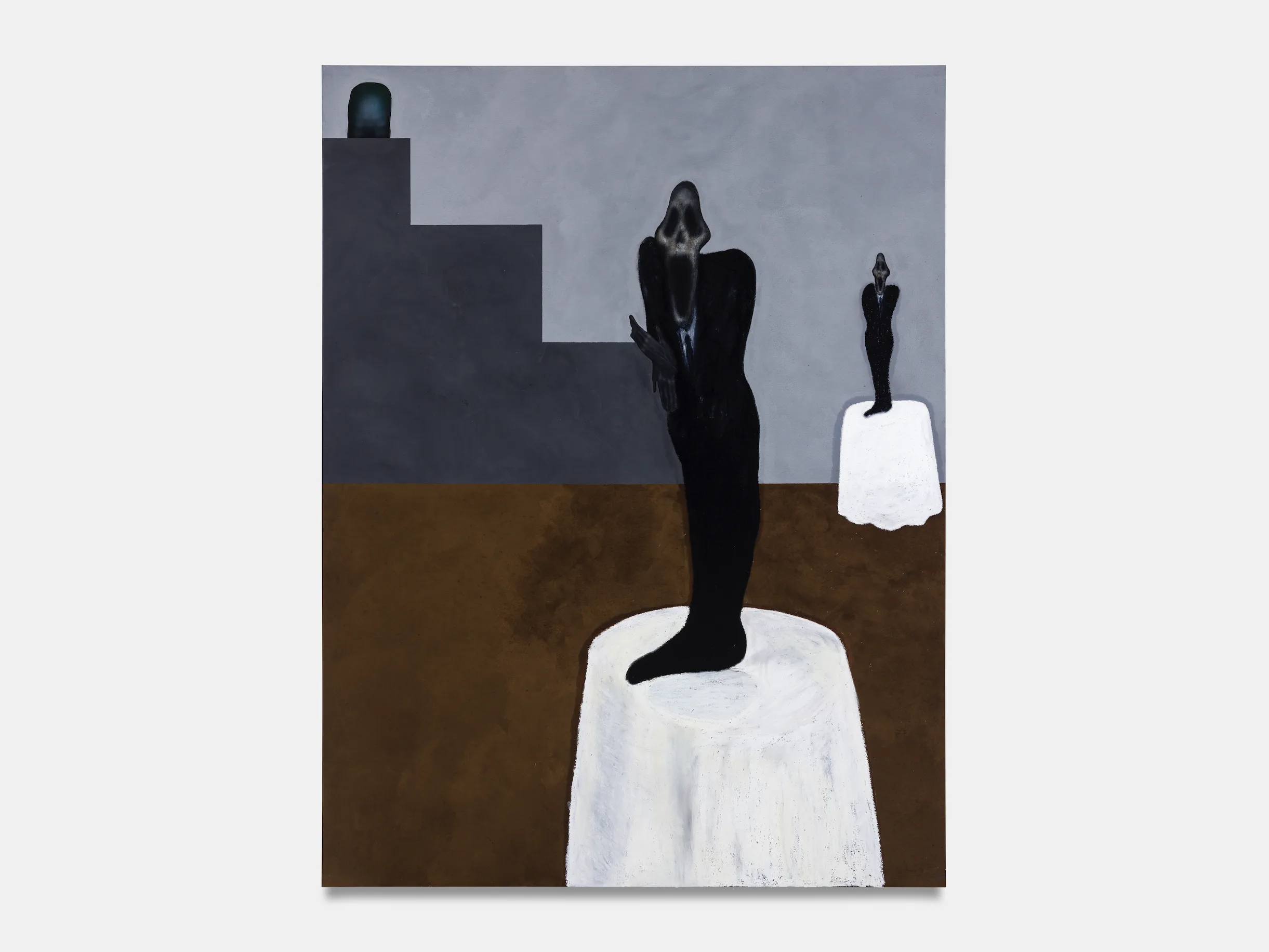

At the end of this aisle is the exhibition’s narrative conclusion: Desire and stones (2025). A work of particular pertinence to Pol, it is the only piece not specifically painted for the exhibition. The work constitutes a conceptual altarpiece; in the place of Christ, we witness two figures with gaping maws, their frozen expressions of horror evocative of Munch’s The Scream. The notion of duplication is crucial; the figure in the rear is at once an emanation and reflection of the primary subject, the stairs in the background are topped with a rounded form that represents “a kind of death,” or an angel. Like an updated version of a 17th century Vanitas painting, the work flips the notion of a memento mori on its head. In the typical former, a skull might be painted into the background, in representation of death’s imminence. Pol not only brings this skull forward, but makes it the protagonist in a move emblematic of the willing confrontation of mortality, inherent to the artistic and ritual traditions of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora.

Within Desire and stones, Pol makes recourse to sequence, a key characteristic of the sense of shift inherent to this body of work. We witness recurrent motifs throughout the exhibition: the white table cloth – which features in five out of 10 paintings – and ominous figures adorned in pointed hats, which constitute the subjects of seven works. The use of reiteration is novel for Pol, for whom “repetition was hard before, because I was thinking being repetitive was being boring.” The use of motif speaks to the artist’s proclivity for symbolic objects, ones “that can open to other dimensions, to other types of reading depending on who you are.” Within the thematic context of the exhibition, the conical hat can be read as a reference to the uniform of the perpetrators of the Spanish Inquisition, to the coverings donned by the Klu Klux Klan, or perhaps to the wizards and witches that populate the surreal realm that the subjects of Pol’s paintings similarly occupy.

In The loud dust under the sofa (2025), three figures sit, hunched-shoulder to hunched-shoulder, their elongated visages bedecked with the tall, pointed hats. Their table bears the stark white cloth that has become a familiar element, another central form with myriad meanings. For Pol, it is at once a metaphor for concealment, a representation of bourgeois ideals of luxury and presentation, and a harbinger of mortality – a cloak a child might poke two holes in and don like a cartoonish ghost. In the rear of the work, two figures clad in grey sit at a lower table covered in a murky, mustard fabric. A solid grey floor meets a band of salmon-pink; the viewer is left to wonder whether the subjects are inside or outdoors. This de-contextualisation is part of the wonder of Pol’s practice; the viewer is given the freedom to fill in the narrative gaps with their own subjectivities and suppositions. In this interstice, we are reminded of the silence of the exhibition’s title: the opening up of space that allows one’s stories to pour in.

Very white teeth, waxed tongue (2025) depicts three men, their gaze slightly turned to the right. Upon the tables surrounding them rest two mummified figures at the scale of infants. An inherently morbid composition, the work speaks to Pol’s commitment to confronting violence critically: “There is violence everywhere; there is violence all around you permanently – if it’s not happening in my work, that means for me that I ignore it.” And yet, despite this, Pol’s paintings evade total morbidity. When asked about this balance, the artist references the use of colour as the language of joy. Rendered in hues that bely accuracy, Pol’s refreshing ambivalence to realism demonstrates his democratic approach. Constrained in their use of gradation and painterly techniques, the works’ visual language is one as easily understood by those deeply familiar as it is to those fresh to the history of art.

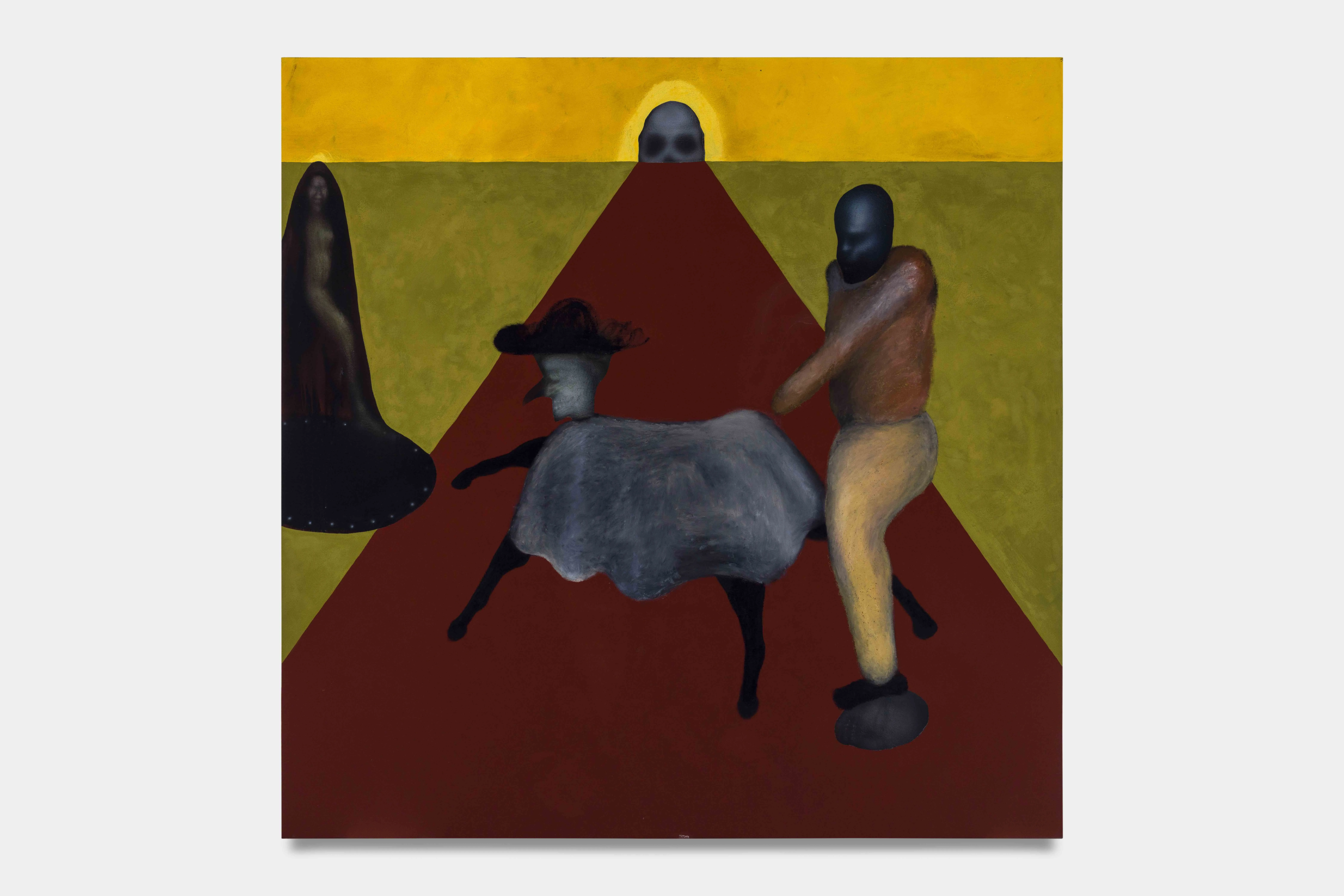

A painting exemplary of this is Perfumed dress and goat clogs (2025), in which a body straddles an ambiguous beast, gazed upon by another, hooded figure, shrouded in black fabric. A red-hued runway stretches towards a golden sky, culminating in the presence of skull-like entity casting its judgement over the scene. The implied narrative is one of pursuit – a relentless chase that underscores a central theme in Pol’s work. “The hunt of bodies – human chasing human, human chasing animals,” he reflects, is present in the exhibition’s accompanying soundscape. The blare of fanfare-like trumpets heralds this vicious circle of predator and prey, the inevitability of death contained in a harmony that “is never going somewhere,” that is “just kind of falling apart, in a way.”

Shown alongside the paintings are pages from Pol’s notebooks – scrawls and sketches housed in four glass-topped tables, displayed for the first time. The smudged charcoal and raw, ripped margins of the drawings find contradiction with the precise angularity of both the Pabéllon, as well as the sharply-edged forms and use of colour that characterise Pol’s paintings. Constituting an exhibition within the exhibition, the drawings are augmented by sheets of concrete-esque poetry; the block capitals printed in both English and French speak to the fluidity – the straddling of distinct worlds – that is a constant presence within Pol’s work.

The exhibition is at once a culmination of and a departure from Pol’s practice: there are the hybridised figures we have come to love and know within his riotous panoply of subjects – some with stumps in lieu of digits, others with additional appendages; some floating in space, others lampooned, abridged, and amputated – as well as new protagonists with a more pensive sensibility. Man and beast as distinct terms are treated with playful indifference; signifiers such as gender, age, and species are relegated in service of communicating the work’s essential feeling. The remarkable nature of the paintings is furthered by their scale – striking, the subjects are made larger than life. The legacy of surrealism and colour field painting inherent to Pol’s distinct artistic language endow the works with a palpable, Rothko-esque sublimity. The primary takeaway from the exhibition is the importance of openness – the willingness to perceive the world in its entirety, with all the good and bad that defines perceptible planes, as well as the multiple universes in between. Perhaps it is best summarised by the Pol himself, an artist who wants “to paint all of it.”

Words by Katrina Nzegwu