Eloise Hendy reviews ‘Nature Painting Nature’ at Pilar Corrias. The show, curated by Lydia Yee, takes Frank O’Hara’s 1954 essay ‘Nature and New Painting’ as a starting point. In O’Hara’s essay, he writes about what he describes as ‘the siren-call of nature to young painters.’ At Pilar Corrias, it is clear that the contemporary artists on display have been lured in and beguiled by it.

When I was a kid, my family would go on summer holidays in Cornwall. Each year, we’d stay a few miles from Penzance, in an annexed apartment, which had platform beds for my younger brother and I to sleep in, and a sprawling garden that backed onto woodland where we’d forage for stray paintballs. One summer, when I was about ten, we climbed a hill earby that was covered in gorse. At some point on the way back down we lost track of the path and got stuck. The whole descent probably only took twenty minutes or so, but in my memory we were scrambling through gorse bushes in the midday heat for hours. Now, whenever I see gorse – or even the yellow of its flowers – I can sense thorny scratches on my shins, sunburn flushing on my neck and, more distantly, the smell of paintballs.

It was this cluster of sensations that hit me as I was standing in front of Jane Freilicher’s painting The Season (2005), which is currently being shown as part of Pilar Corrias’ new exhibition Nature Painting Nature. In the foreground of Freilicher’s work, a tree is bent at an almost impossible angle, its branches jutting up from a trunk that seems to snake along the ground. This surreal tree, grasping like a skeletal hand, stands in a wash of yellow – pastel smooth in places, but elsewhere tangled with scribbly strokes, as if alive. A field of wheat perhaps, but, to me, the scratching and grasping of gorse bushes, with a distant blur of blue water acting as a taunting vision of serenity; of escape.

I doubt anyone else will feel phantom abrasions looking at Freilicher’s painting, but the prickling of personal memory felt apt for this group exhibition, which brings works by Jane Freilicher and Grace Hartigan together with that of contemporary artists, to explore how different generations of painters both approach nature as a conduit for sensation, memory and self-expression. This is “nature painting” at its loosest, where personal experience is the true subject. Rather than traditional “landscapes”, these are landscapes of the soul.

Curator Lydia Yee takes Frank O’Hara’s essay, ‘Nature and New Painting’ (1954) as a starting point. Here, the pre-eminent poet of New York City, Coca Cola and instant coffee focuses on a generation of New York School painters who filtered their experience through natural subject matter. “There is a kind of painting, which looks to be about nature but is lacking in perceptions of it,” O’Hara writes. “Here the painter utilises his visual experience for subject matter, but his experience is the subject, nature is not.”

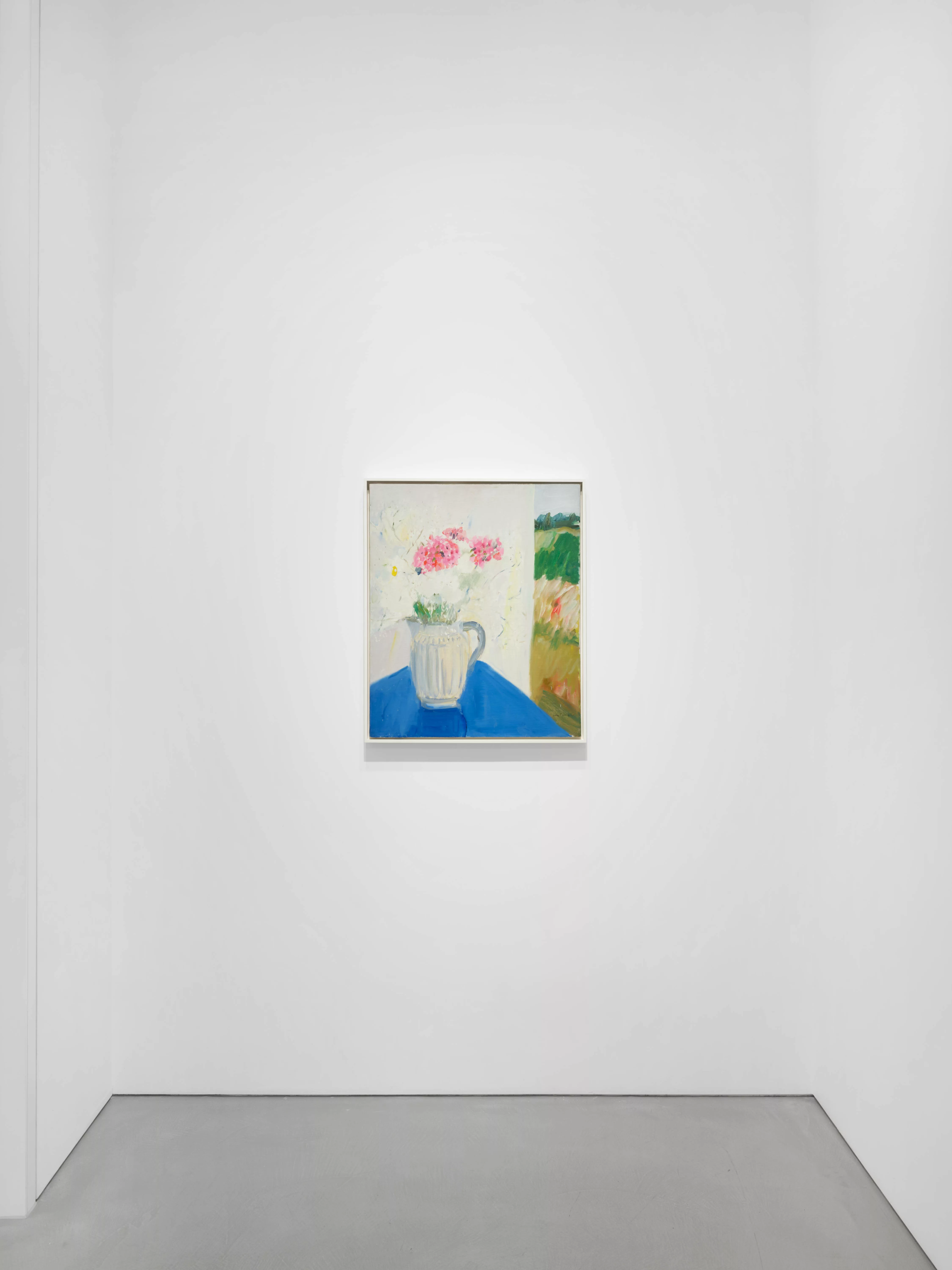

Jane Freilicher and Grace Hartigan are two of the artists O’Hara considers, and in Pilar Corrias’ show their works act as touchstones – points of contrast and uncanny comparison through which to look at the contemporary paintings that surround them. Near The Season, for instance, is an earlier Freilicher painting, Blue Table (1966), which could perhaps be dubbed a “still life”. Yet, despite portraying a typical domestic scene – a vase of flowers on a table – there is a bristling energy to the work, and an element of abstraction that pushes against the representational. A leaning flower looks like a cartoonish fried egg, bright pink blossoms are all brush marks, and white petals seem to wash into translucence. Is that wavering block of light colour on the left side of the painting wall or canvas? And on the right – that thrusting, dynamic slice of outdoors that looks at once like a Bonnard-esque open window, and an abstract expressionist painting in its own right? The longer you look at Blue Table the less it looks like a still life, the more like a dreamscape. “Miss Freilicher’s responsibility seems to be to her perceptions rather than to painting,” O’Hara writes in his ‘54 essay – “the originality of her colour, for instance, comes… from a sensibility liberated from self-consciousness by its intense occupation with what it perceives and means.”

A similar urge is in Grace Hartigan’s Tide Pool (1972), which blends watercolour and collage. “Her paintings are full of nerves and senses,” O’Hara writes of Hartigan: Tide Pool swims with strange, leggy creatures, marine life forms with bumblebee patterning, and bright red water-blooms. A zig zag fracture exposes a slash of blue like a cut waterway, an open wound. There is something faintly childish about it too though – that zig zag – reminiscent of kids’ collages made with safety scissors. But, like the gorse, perhaps that’s just me: by taking personal experience as the true subject, these works invite free, nostalgic, personal associations.

In O’Hara’s essay, he writes about what he describes as “the siren-call of nature to young painters”. At Pilar Corrias, it is clear that the contemporary artists on display have been lured in and beguiled by it. On the adjacent wall to Hartigan’s Tide Pool are three small works by Vivien Zhang. Peer closely into Zhang’s hot floral flushes, peppered with seed pods as darkly lustrous as black pearls, and you can see lines between the works’ different layers. These paintings, which at first appear to have a digital quality to their pristinely blurred out backgrounds, strike up a perfect dialogue with Hartigan’s collage work. There is something undeniably sexy about Zhang’s hot, unfurling petals spilling with seeds too – her paintings don’t so much respond to a siren-call as enact one.

Another highlight greets visitors at the door: Francesca Mollett’s Nacre (2024), which seems to glimmer like a pretty oil slick, a small luminescent pool. Mollett sought to capture “the iridescence of mother-of-pearl,” Yee writes in the exhibition text, “or the shimmering of spindrift”– the spray blown from cresting waves during a gale. Working with oils on linen, Mollett pulls the paint so smooth and thin in places it does indeed look like the glossy inner shell layer of an oyster; elsewhere the colour clusters in deliciously tactile scoops. Nacre strikes me as a distillation of a mood, rather than a single natural subject. As Mollett herself has said, she wanted to create a “shifting feeling in the surface of the painting through colour”.

This “shifting feeling” recurs across other works in Nature Painting Nature – perhaps most notably in Leiko Ikemura’s Trees (2013), and trio of paintings Lake Biwa (2019-20). In Trees, which sits winkingly close to Freilicher’s twisted skeleton hand, two red trees seem to bloom from a wet red seam – the earth’s lifeblood perhaps. At one glance, this painting is a scream; gory forms reaching out of the ground. Then, it seems to shift into a dance, the trees becoming figures moving in harmony with each other. Similarly in Lake Biwa, the canvases swing between cuteness and menace, conjuring images like an ink blot test. Is that an animal in the middle canvas, throwing back its head and howling? Above, a red wash looms — a flower with seeds swallowing the dog whole? A wash of blood, a cloud, a burst of smoke?

Towards the end of his essay, O’Hara considers the work of Wolf Kahn. He suggests Khan “sees impressionistically… He sees millions of collars on each leaf, he sees light breaking over a face like foam, he sees an eye rolling in an abyss of pearly hues, he sees the sun shedding its gold over the landscape like blood”. Looking at Zhang’s black pearl seeds, at Mollett’s shimmering spindrift, or Ikemura’s hazy washes of red that also shed over her landscapes like blood, it’s clear that here too the “paintings are very beautiful and very serious; very rich and very sad; very bright and very heavy”. It is also true that, standing in front of them, “one is not always in command of oneself or of the experience, and as one sees longer it becomes apparent that an unknown quantity of perception is available to one’s flagging powers, as in nature the hidden secret is partially revealed – or else,” O’Hara teases, “this is the mysterious quality of painting itself”. Ultimately, whether the “shifting feeling” these works evoke speaks to the mystery of perception or of “painting itself”, the exhibition certainly calls forth what O’Hara describes as “the prolongation of sensation into the future”: “you see, you absorb, you perceive, you paint, you see anew.”

Words by Eloise Hendy