With over two hundred works filling four galleries, in States of America: Photography from the Civil Rights Movement to the Reagan Era–the first show at Nottingham Contemporary to be dedicated solely to photography–the action of storytelling is acutely preserved through the lens of Hasselblads and Leicas, peeling away the skin of society to reveal everything from a homeless child’s struggle for basic survival to the banality of suburban living. The opening display is given over to Mark Cohen, who spent most of his life documenting the goings-on around his native Pennsylvania, with an obtrusive style of shooting that employed a wide-angle lens and a flash unit–a stark contrast to the clandestine approach taken by the likes of Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand, both of whom are also featured in this show. This invasive method meant that many of his subjects looked straight through the image with a performative, knowing presence or conversely attempted to shield their face from view.

Cohen’s work also represents the revolutionary moment when documentary photographers began to shoot in colour. Despite the availability of Kodachrome as early as the 1930s it took another three decades for the material to transgress the markets of fashion and advertising and be perceived as a viable “high art” medium. This sudden pigment explosion is presented alongside Cohen’s monochrome projects, and while the subject matter remains the same, the closer, cropped style in his later studies allows one to enjoy the majesty of a filthy yellow shirt or a child’s tanned leg in a way that could never be conveyed through tones of black and grey.

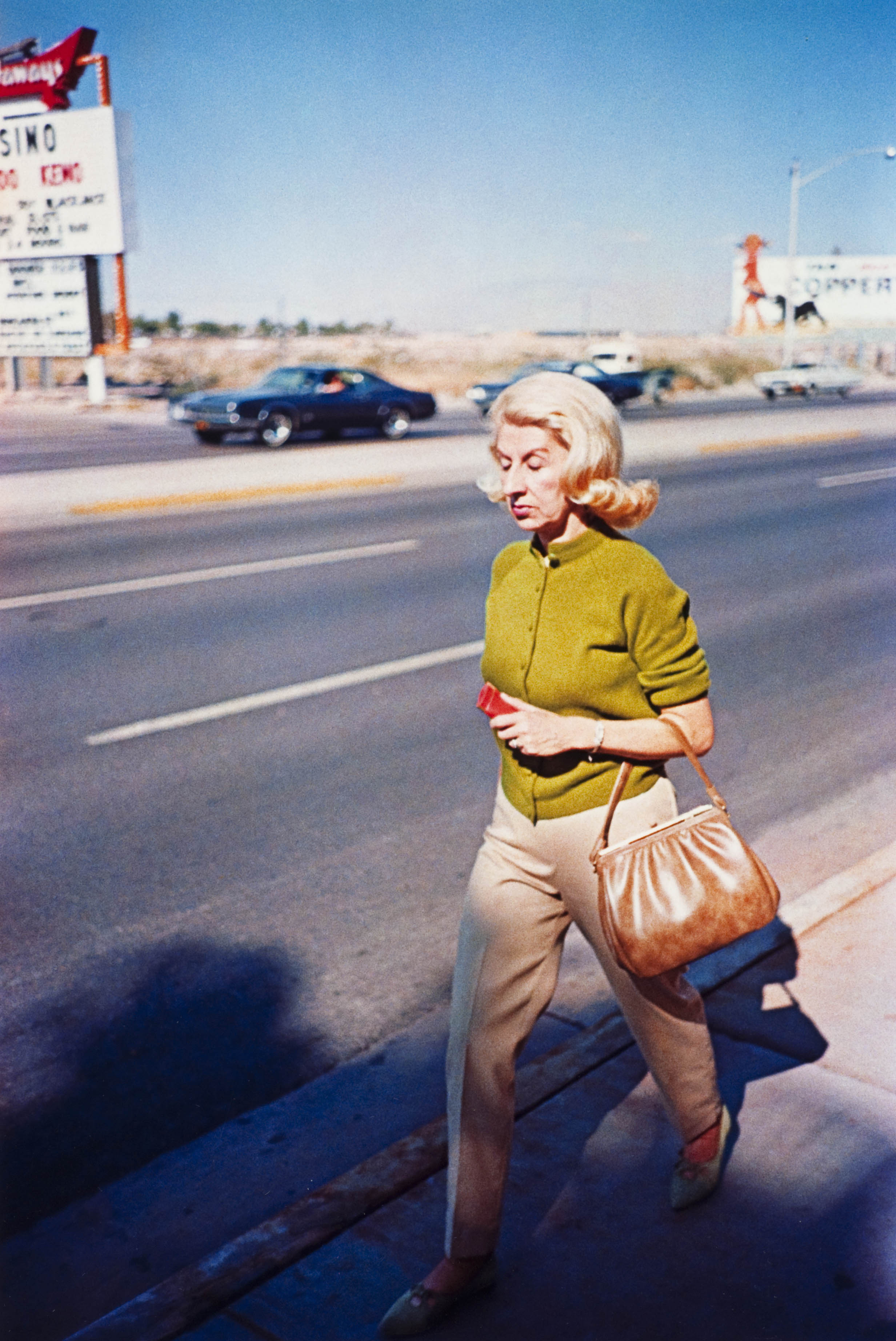

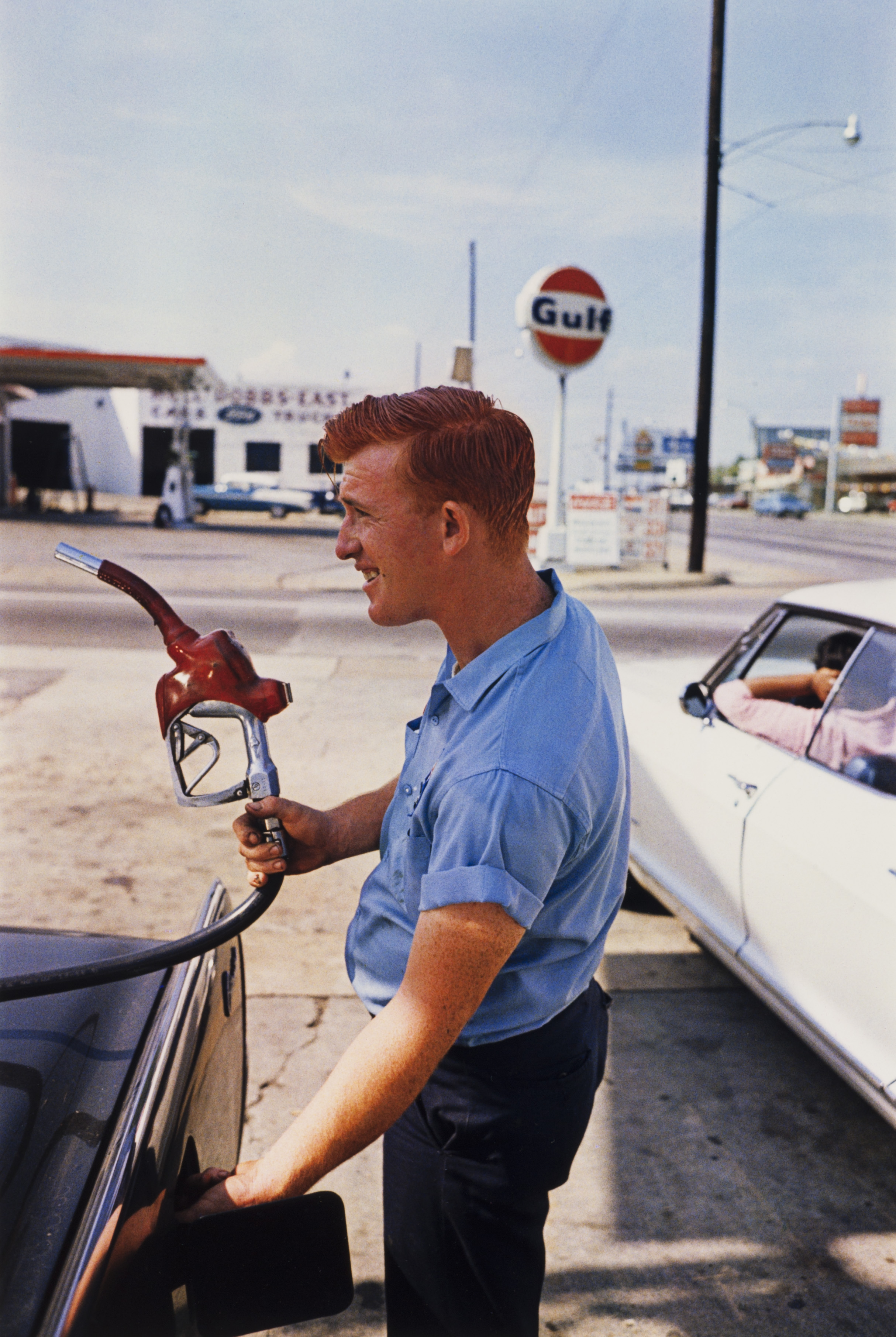

The power of the kaleidoscopic was also enthralling for Stephen Shore and William Eggleston, who pioneered the use of new technologies including dye-transfer and c-type printing. Both photographers found beauty in America’s open roads and took to studying dilapidated storefronts or people going about quotidian activities such as grocery shopping and pumping gas. At the time their work was met with derision by some, with New York Times critic Hilton Kramer referring to Eggleston’s first MoMA show in 1976 as “a case [of], if not the blind leading the blind, at least the banal leading the banal.” Such an assessment seems unfathomable now. These mesmerizing views of a lost all-American society are nothing short of iconic and have rightly gained their makers global recognition and acclaim.

Beyond the celebration of the everyday, other photographers chose to pursue more hardline sociopolitical concerns in their work. Mary Ellen Mark focused on documenting what she called “the unfamous”; those who lived on the fringes of society. This led to a thirty-year project following the life of a prostitute named Tiny, who Mark met on the streets of Seattle when she was only thirteen years old. These intimate portraits vary from close-ups of Tiny’s sullen face to broader glimpses into her chaotic home life, revealing the cyclical nature of poverty she and many others endured.

These images share a commonality with the wider known work of Diane Arbus, who also sought to shine a light on marginalized communities. However, this was by no means her only focus. The images presented in this show demonstrate her interest in the intimacy found within couples and families, as well as one striking shot of the foreboding aristocrat Mrs T Charlton Henry, which recalls Arbus’s roots in fashion photography.

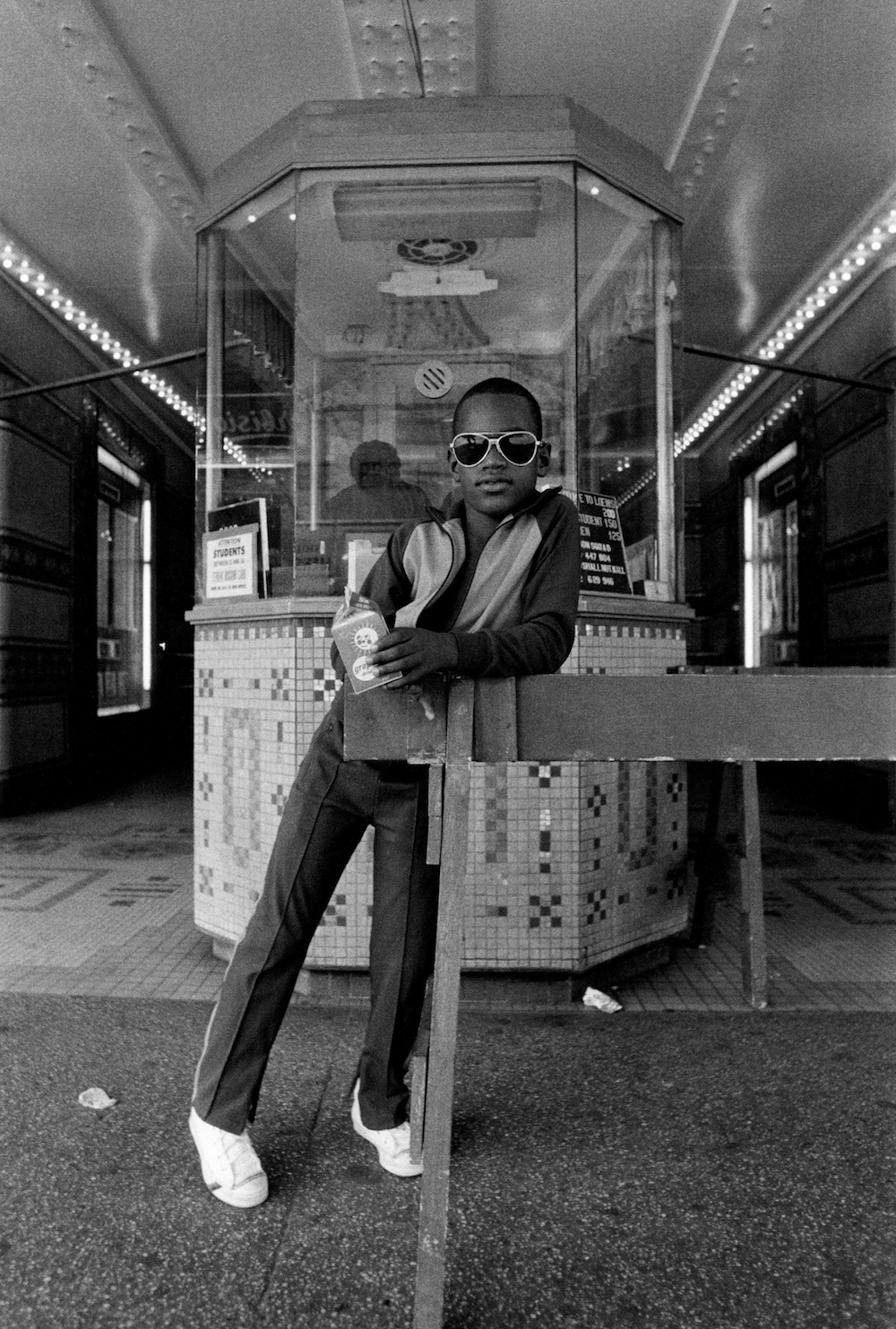

Dawoud Bey, A Boy in Front of the Loew’s 125th Street Movie Theater, 1976, gelatin-silver print. © Dawoud Bey, courtesy of Stephen Daiter Gallery

Jim Goldberg went even further in documenting the chasms of the American class system in his decade-long series Rich and Poor

. Using both photographs and handwritten testimony from his sitters he created something of a social census, juxtaposing the woes of the one percent with those of the welfare state. By shooting his subjects in their homes the evidence of mass disparity is compounded. A wealthy housewife laments the burden of instructing staff while languishing in her apartment, whereas a poverty-stricken youth declares he only has ten dollars to his name and despises seeking shelter in a “stinky hotel”.

“In the dying light of the day Davidson captured an enormous cross-section of the population, as people from all walks of life made their daily commute on graffiti-strewn carriages.”

These heart-breaking accounts are one of the most arresting elements of the exhibition. Ironically, through the power of the written word Goldberg’s photographs transcend the elements of nostalgia that often become tangled in images of Cadillacs, shop fronts and shady street corners. In a way these texts ignite the deeper readings infused throughout every photograph on show, demonstrating how painfully pervasive themes of poverty, alienation and political upheaval remain to this day.

The ultimate example of this lies in Bruce Davidson’s huge portfolio, which has been given sizeable due in this exhibition. He is perhaps best known for his grainy black-and-white action shots of Brooklyn greasers taken in the late fifties, but it is his colour images taken two decades later, chronicling the world of the above-ground sections of the New York subway system, that are truly formidable. In the dying light of the day Davidson captured an enormous cross-section of the population, as people from all walks of life made their daily commute on graffiti-strewn carriages, well before the citywide clean-up in the late eighties. Warm, honeyed tones fall on the faces of businessmen, church-goers and young punks alike, in what appears to be a romantic vision of a somewhat egalitarian space.

However, this notion is quickly shattered by a final image of a man cowering by the subway doors–a gun pulled to his head. This shocking, violent vision is a powerful reminder of the disparity and tension that so many of these photographers seek to convey in their work. Even when the subject is banality, these images speak to the dangerous nostalgia that permeates much of present-day American politics, which often removes these shots from their original context or any wider form of critique. Whether it is through the beauty of a run-down store, the horror of widespread poverty or the disenfranchisement of youth, these photographs embody an underlying hostility and disaffection that continues to permeate every strata of American society to this day.

“States of America: Photography from the Civil Rights Movement to the Reagan Era” shows at Nottingham Contemporary until 26 November