To understand the Bengal School’s formation in the 20th century, you need to travel back several hundred years. Back to 1613 when the British East India Company set up its first factory and trading post. Back to 1757 when the British took control of Bengal, India’s wealthiest province. And especially back to 1876 when Queen Victoria officially assumed governance of the nation.

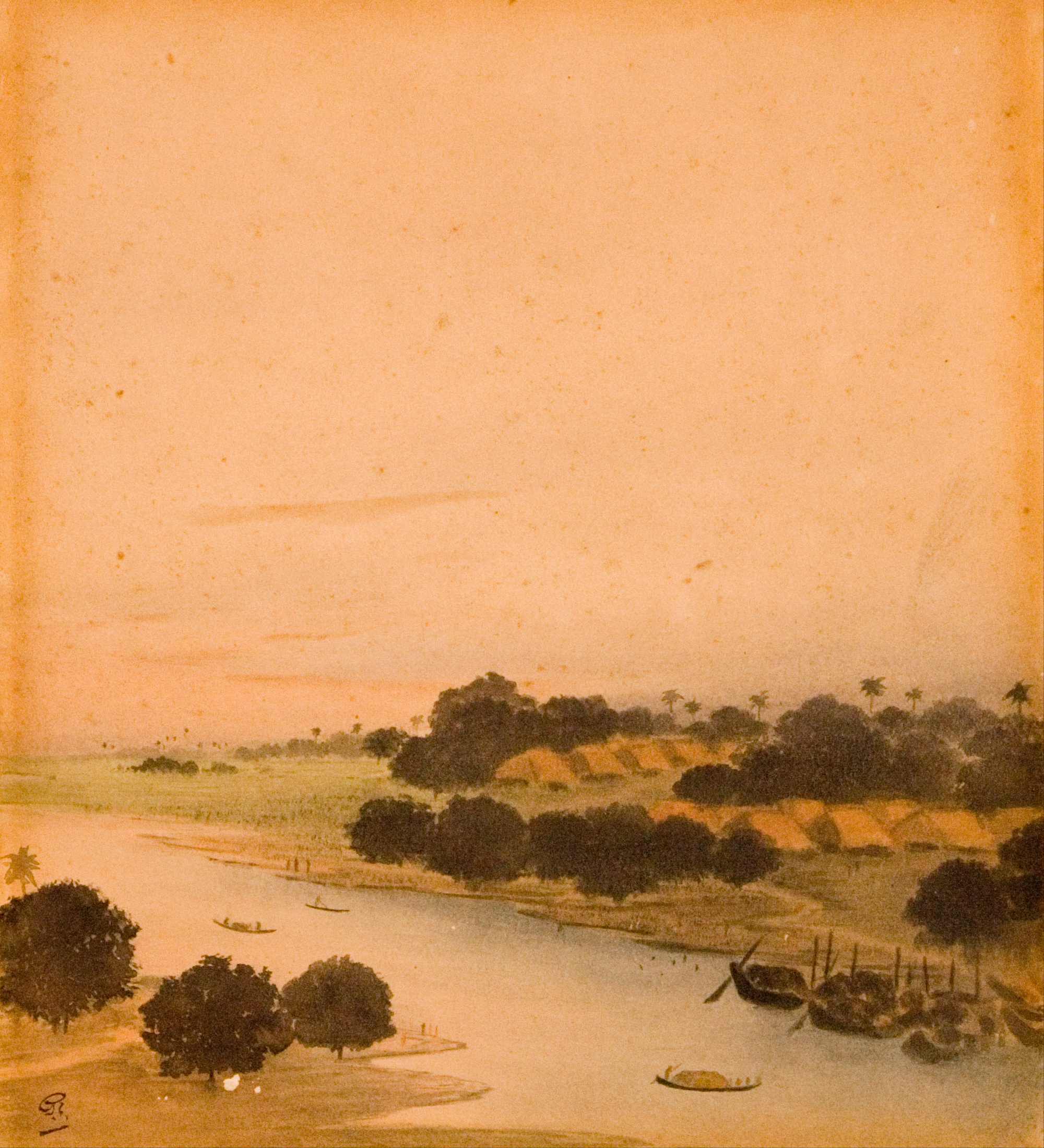

Faced with this colonial control, Indian artists of the day quietly reflected the sociopolitics of the time. Styles echoed British tastes, as seen in the Company Paintings, which appealed specifically to British collectors and embodied a ‘realistic’ style that aimed to document Indian life through a colonial gaze. A far cry from the traditional work which visualised religious epics, drawing heavily on natural pattern and sumptuous colour, Company Paintings mostly manifested as careful watercolours that utilised linear perspective and delicate shading.

During the early 20th century, the revered Bengali poet and intellectual Rabindranath Tagore (who was involved in the Indian nationalist movement led by Gandhi) championed the notion that that creativity could be synonymous with national identity. Tagore’s nephew, Abanindranath, helped to form The Bengal School of Art alongside a British teacher at the Calcutta School of Art, Ernest Binfield Havell, who had originally arrived in the country in 1884 to report to the colonial government on the arts industry.

“They eschewed the British realist constraints and sought to reclaim an Indian audience”

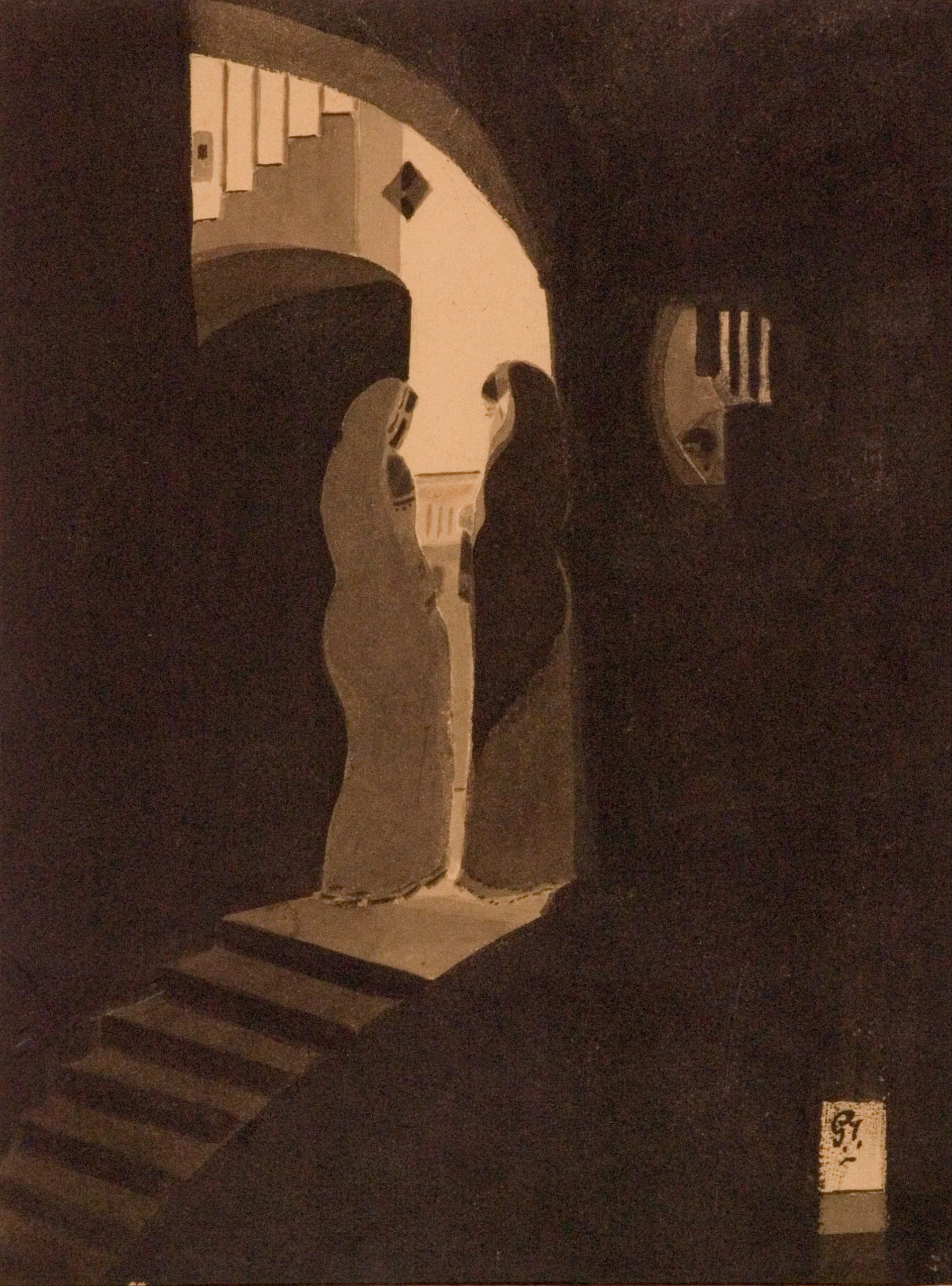

Havell grew tired of the British traditions imposed on Indian arts education and (despite the protests of his peers) encouraged the study of Mughal Art, instilling pride in the South Asian heritage of the students. Derived from the Persian miniature painting tradition, and combined with Hindu, Buddhist and Jain influences, this style flourished in the courts of the Mughal Emperors from the 1500s onward.

Born in Jorasanko, a Bengali town, and inspired by his uncle, Abanindranath Tagore channelled his love for the country into the visual arts. After enrolling at the Calcutta School of Art in 1890, he (alongside his brother, Gaganendranath) pioneered the Indian Society of Oriental Art in 1907. It was heavily influenced by the Swadeshi movement, sparked by the government’s decision to partition Bengal, and described by Gandhi as the soul of self-rule.

Autonomy was central to the Tagores’ philosophy, and they began to exhibit artists from their new movement. Sponsored by a group of Europeans, including senior British Army Officer Lord Kitchener and judges from the Calcutta High Court, the Society also played an important role in furthering research into indigenous art. They also solicited the artists Nandalal Bose and Asit Kumar Haldar to explore the famed Ajanta caves and document the murals there.

Bose was later invited by Gandhi to produce political work. Inspired by the Ajanta murals, he also preserved the 1930 Dandi March in the nation’s memory with a series of sketches of the political leader in heroic compositions. Haldar, meanwhile, used his Ajanta studies to fuse Buddhist art with Indian history, and was later celebrated as the first Indian to be elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, London.

The Bengal School emerged out of this work as a movement that encapsulated a national artistic aesthetic. It embodied the values that Havell and the Tagores espoused, embracing Indian history and reclaiming control of the country’s culture. Using indigenous materials and a warm, muted colour palette, these artists eschewed the realist constraints that the British had introduced and sought to reclaim an Indian audience.

- Portrait of Sunayani Devi, author unknown, photograph taken before 1924 (left). Sunayani Devi, Untitled (Krishna), circa 1920s (right)

“The Bengal School was heavily influenced by the Swadeshi movement, described by Gandhi as the soul of self-rule”

The Tagores’ sister, Sunayani Devi, was best known for emulating a primitivist style, inspired by Indian folk art, and used this visual language to depict mythological scenes. Her work bridged indigenous styles and modernism, synthesising cultural identity and contemporary experimentation. One could imagine that the Hungarian-Indian artist Amrita Sher-Gil had seen Devi’s work and evolved the style further into the modernist realm. Sher-Gil in fact thought the school retrograde, and suggested that it played a part in inhibiting the progression of Indian art. This criticism was shared by the postcolonial Bombay Progressives: assembled shortly after the British exit from India, they were intent on evolving South Asian Modernism beyond what they saw as the overly-indigenous style of the Bengal School.

However, it’s likely that without the influence of the Tagores, the mid-century work of FN Souza and MF Husain (which transformed the Indian art scene) could not have come into being. The Indian Society of Oriental Art still has headquarters in what is now known as Kolkata, and the government College of Art and Craft train students “in traditional styles of tempera and wash painting”. The Bengal School’s influence remains an instrumental part of South Asian history.