Cartoonish sperm sculptures, anthropomorphic assemblages, and, of course, a choreographed maze of stanchions: the young New Yorker has the art world lining up to step into his office.

“The foul lump in my throat,” Louis Osmosis calls out to a bespectacled man with a shock of white hair who is slowly walking out the door of Walker’s, the art-world watering hole in Tribeca. The man looks up with slight surprise at being recognized, then curiosity. He is the acclaimed postmodern poet John Yau. Who is this young man quoting his prose from 1989, he inquires.

“If you see the show and think American dream, that sounds like a you problem.”

Osmosis is an artist who operates in dualities or, better yet, trialities. “The third time’s the charm,” he tells me on a rainy afternoon at Kapp Kapp, where his solo show “Queues” runs until March 9. His found, manufactured, and bespoke assemblages shift between impenetrable and playful. Like Yau—whose narrator in the aforementioned poem is ventriloquised by said lump—Osmosis is interested in the charged possibilities that arise when objects are estranged from their formal definitions. More simply put: he is drawn to the spot where sculpture and poetry converge.

The artist lays down underneath a maze of stanchions as I crouch across the room with my camera. Sequestered from the readymade pathway, various assemblages are lined up against the wall, all made this year. Fabric spills out from industrial-looking boxes (labelled Content Houses), a riot shield levitates over a clear acrylic tube next to a vintage high chair with a steel stove pipe erected through the centre.

His stanchions overtake any preexisting agency that the viewer might have. In America, bureaucracy is packaged as a collective purpose: lines and paperwork are behind every corner, in hospitals, schools, airports, amusement parks, and government institutions.

If you can’t stay in formation, you won’t make it to the front. “This fucked up infrastructure actually works to possess people in a way,” says Osmosis. “It’s very self-aware, and it’s very self-sufficient.”

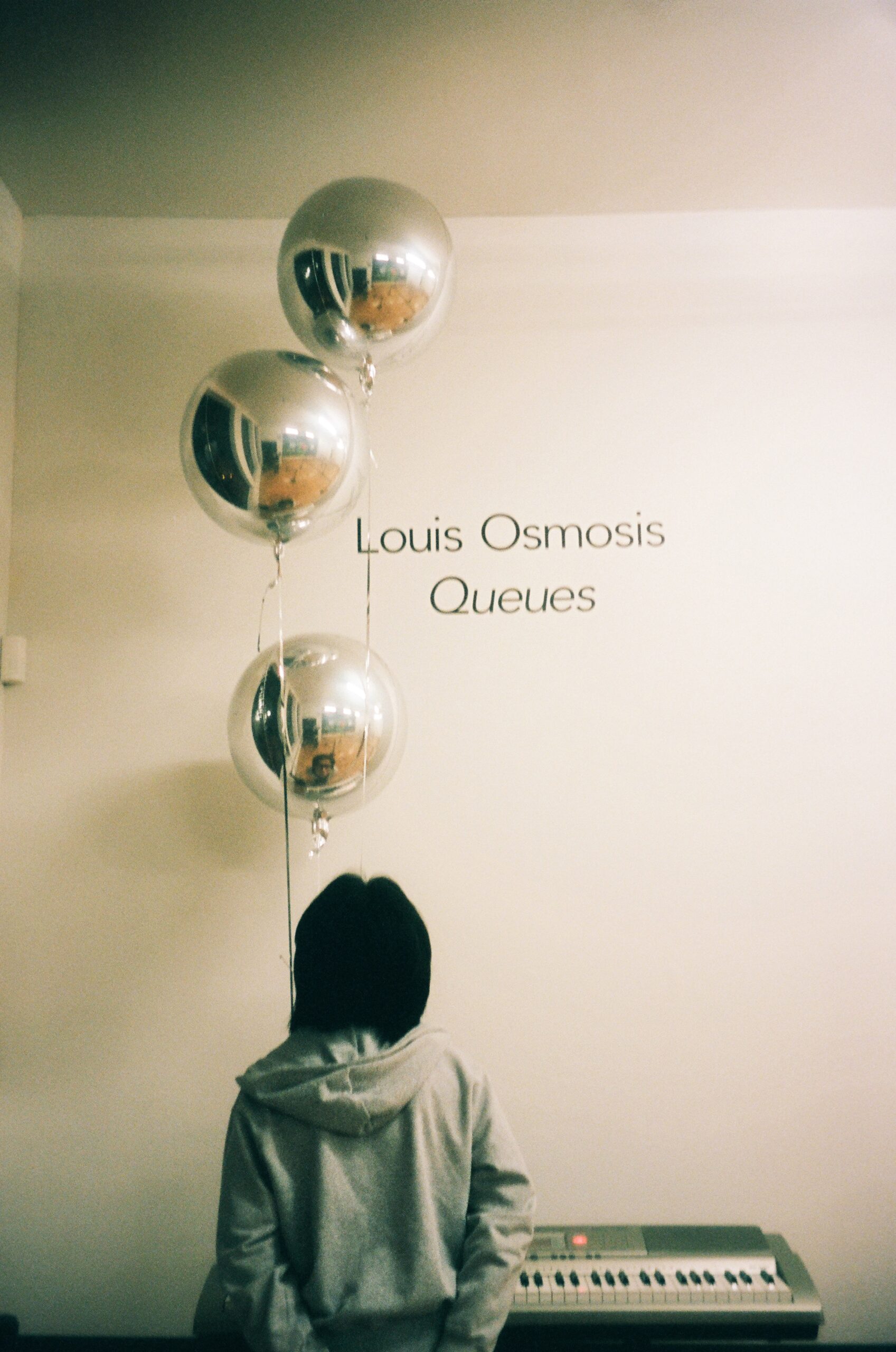

A few days earlier, when I first visited the gallery, I exited the elevator and was greeted by Score, for Ellipsis & Roundtable, in which three silver balloons hover above a piano keyboard with an AM radio resting on it. A discussion about the American dream reverberated from the transmitter’s small speaker. I gingerly stepped into the orderly line of guests, packed like sardines, making their way across the room. At one point, an angry visitor approached a stanchion to berate a young woman in line over how long she spent in the bathroom; it was a scene straight out of DMV purgatory.

When I recount the evening with Osmosis, he laughs recalling the way the line seemed to both animate and subdue viewers. He shakes his head no when I ask him if the audio was pre-recorded. It just plays whatever is on the program for that day, he says. “If you see the show and think American dream, that sounds like a you problem,” he adds with his New York inflection: “I’ve never heard of her.” If you’re second guessing what it is you’re looking at, that’s the point.

“What does it mean and what is implicated when you produce a cultural object?”

Yet “Queues” is not not about that heavy and cliched phrase, either. Rather, the subtext gives the exhibition something to sink its teeth in. Afterall, stanchions are mass-produced harbingers of order, dispersers of the other, invisible conductors, synonymous with neoliberalism. Reinforcers of a look-but-don’t-touch policy, they keep us all in line for better or worse. (It’s worth noting that at the opening, I saw nary a soul attempt to hop over or under the dividers). In a sense, waiting in an orderly fashion is an intrinsically American habit. Look to various cultures, and you’ll find this is not par for the course everywhere.

Osmosis recalls an epiphany he had while waiting in a long, accordion-like TSA row at an international airport in Italy. His vantage point synced up with shelves that displayed replicas of various contraband: a Supreme x Louis Vuitton bag, an ivory tusk made of plastic, fake versions of the real things. “I noticed the inherent poetics within them,” he says, “the effort to, essentially, create something that should negate itself, to name something you shouldn’t have with you.”

In his practice, the artist stretches this idea until it is almost translucent. “What if I took my liberty with Liberty?” and “How can I make the most wall-y wall?” he asks. “Put up bad wallpaper, and make these hyper-fabricated facsimiles,” he gestures to the blown-up Statue of Liberty-by-way-of-Getty-Images print that envelopes one wall of the gallery, dotted with three red, silver, and grey paper-mache sculptures that look like plastic props of boarded up windows.

Off to the side of the wall, a giant, shiny white paper-mache sperm sculpture stands in an animated stance. Big Mascot (Ragamuffin), is trailed by a neat row of 3-D printed miniatures, displayed single-file on a table. Each Small Mascot wears a character-imbuing, hand-made cap. There is Butter-Face (sporting a greasy paper bag), Co-Pilot (a rainbow propeller), Weekend Warrior (viking helmet), Orient (a conical, rice hat), Bridezilla (a veil), and Slippery Bastard (a banana peel). Here, rarity is as simple as putting on an accessory.

As we take in the Mascots, Osmosis discusses art theory in the same vein as Mucinex commercials from the early aughts; the ones where a giant, cartoon booger is the mascot for cold-and-flu medicine. These sperm sculptures are the perfect mascot for the artist, he offers. “I thought it would be cool if it could formally look like a descendant of modernist sculpture—think Brâncuși, Henry Moore, Louise Bourgeois—with this sort of belaboured smoothness, this 360-type of sheen,” he says, adding, “It is also the greatest equaliser. Everyone is a sperm at some point.” These cartoonish figures encapsulate Osmosis’ fascination with art-making as family-making, where artistic reproduction begets progeny.

“I don’t want to fall into the trap of being a factory of my own work.”

The concept of lineage as an archetype-generator pervades the gallery. Seemingly incongruent assemblages form a sort of nuclear family made up of various stereotypes, from highfalutin to pop-populist. There is the dead-beat dad, a tiger mom, a tom-girl named Leslie, Osmosis rattles off the various personalities of the works. Chair with Pipe is a bastard son, “a three-year-old who refuses to eat and is constantly throwing temper tantrums, maybe not being loved because the father has yet to admit that he’s an illegitimate child, or something…”

The traits from each work culminate at the end of the queue: A small, rectangular slit in the wall invites a closer look. “You are spit out at this hole in the storage room, at what I will call the I.C.U. unit for art objects, where they go when they haven’t sold,” the artist tells me, adding that this is also where the aforementioned traits end up. “They are preserved here, but in that ossification, they also rupture,” he shares, referencing the pulsing strobe light he placed in the room.

At the heart of “Queues” lies the question of artistic production. “What does it mean and what is implicated when you produce a cultural object?” Osmosis asks. For the artist, who is an avid student of art history, lineage—both macro and micro—is rich material.

The artist’s understanding of the artifice of the everyday, that everything can and should be up for revision, began at an early age. He adopted his moniker, Osmosis, when he was 12 years old, after hearing the term on an episode of “Good Eats with Alton Brown.”

Born in South Brooklyn in 1996—a year after his parents immigrated to America as Hong Kong underwent a contentious transition from British to Chinese rule—Osmosis has called New York his home his entire life. And while his work isn’t autobiographical, it is easy to see how his sense of humour, personal style, and do-it-yourself attitude shapes his practice. His sartorial proclivity (he has a disarming habit of wearing peculiar-coloured contact lenses to his openings, sporting stars and stripes most recently) takes cues from his stylish mother, who owns an eyeglasses boutique and has cropped purple hair and a penchant for Louis Vuitton, Moncler, and Issey Miyake. His construction skills come from his father, a handyman and plumber who can fix anything.

An only child, his foray into art-making was through science experiments: first, the sudsy, toothpaste-and-laundry detergent ones he conducted alone in his childhood bedroom-turned-laboratory. And later, awe-inspiring mechanical displays at science fairs. He went to high school at LaGuardia, and applied to Cooper Union behind his parents’ backs, where he was admitted. There, he fell in with conceptual art, earned a BFA for the Advancement of Science & Art in 2018, and never looked back.

We speak once more, this time on the phone while Osmosis is in London to see his friend, the artist Aria Dean’s show at ICA London and pay his respects to the late Pope.L at the South London Gallery, where the pioneering conceptual and performance artist’s exhibition remained on view for over a month following his passing. “I really respect someone who can produce poetics in an economical way,” Osmosis says of Pope.L, whom he deems the biggest influence on his work. “One of his tenets basically says: It’s funny that people always think about objects as objects, what about their other properties?”

Now, at the tail end of his third solo exhibition, Osmosis is already thinking about what’s next. For the young artist, every exhibition is an allegation to beat: “It’s a cat-and-mouse game, to prevent complacency within my practice,” he says. “I don’t want to fall into the trap of being a factory of my own work.” For his next show, he hints, he is going in a very different direction. What that means, we will have to wait and see.

Written by Meka Boyle