Veronica Stigger reflects on the enduring legacy and complexity of the Brazilian artist’s work.

In an interview published in the 21 December 1968 issue of Manchete, the famous writer and columnist Clarice Lispector asked Maria Martins whether she saw her sculptures “as figurative or abstract.” Martins replied: “I am anti-isms. Some say that I am surrealist.” What stands out most in the artist’s response is not just how she sidesteps the question — refusing any self-definition that would confine her to a particular category or collective style — but rather how she introduces such a classification herself, like “surrealist.” Most striking is that Martins presents this label as coming from the way other people perceive her work: “some say.”

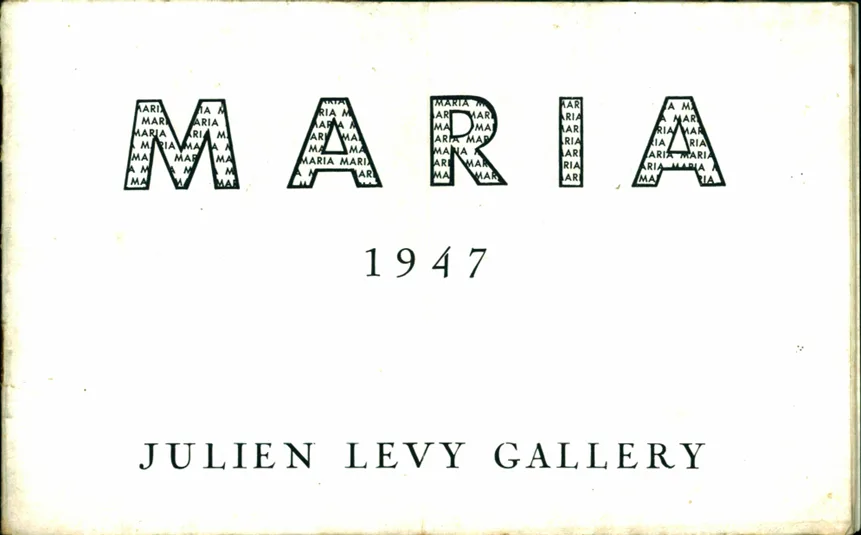

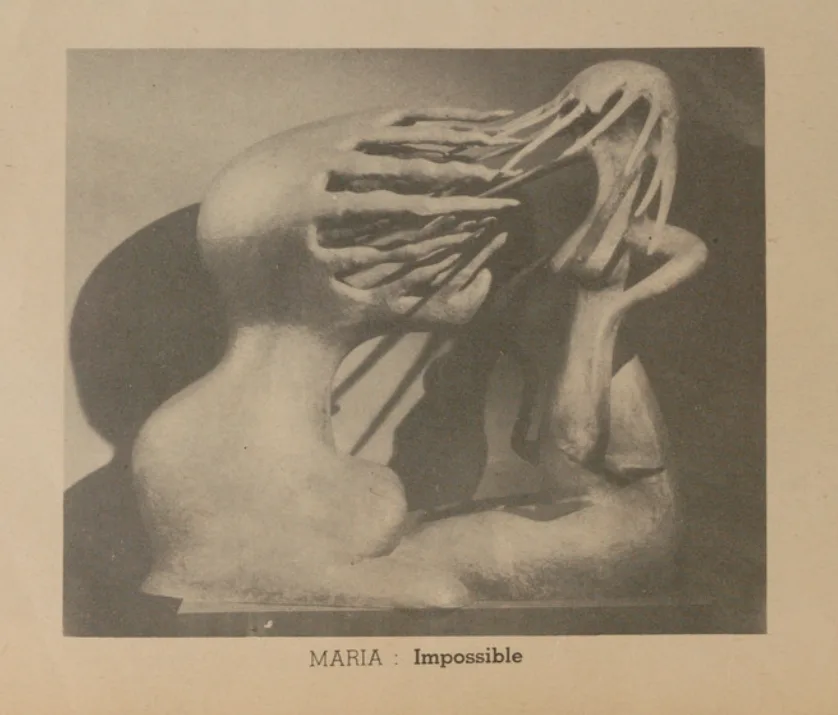

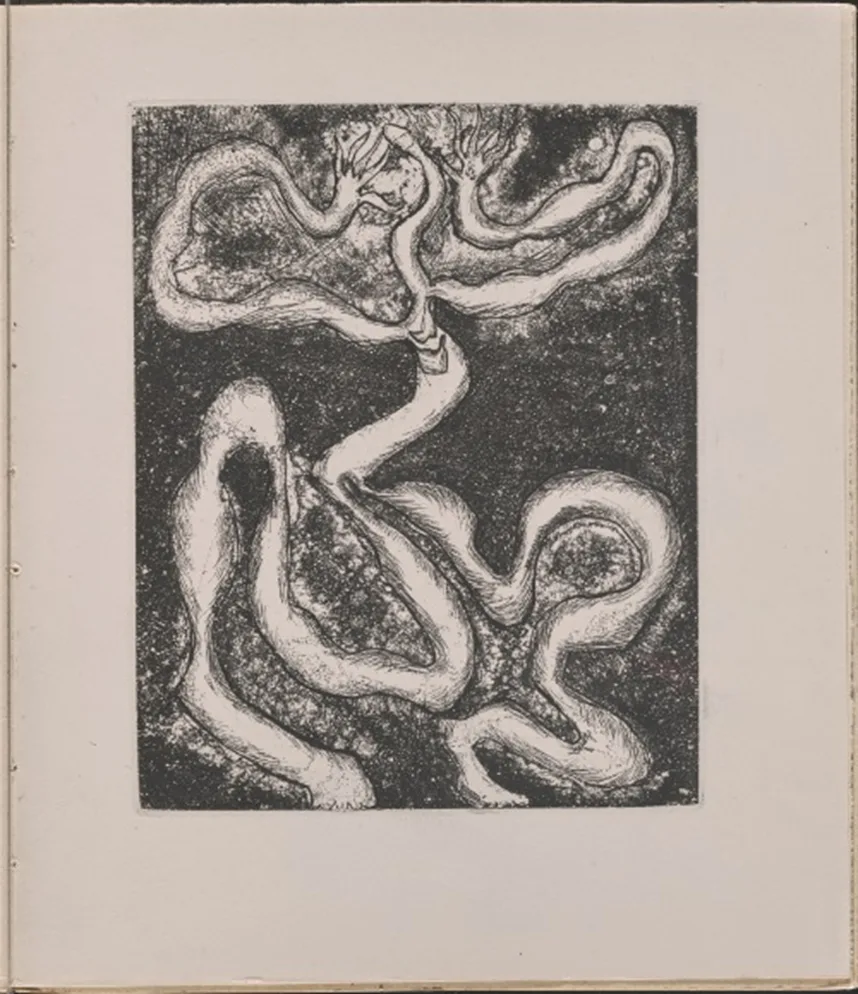

Who says? A lot of people. To begin the list: none other than André Breton, author of the Manifesto of Surrealism — first published in 1924 as a preface to the poems in his book Soluble Fish — and of the subsequent manifestos of the movement. Breton wrote the presentation for the artist’s solo exhibition, Maria: Recent Sculptures, held at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York in 1947. That same year, he and Marcel Duchamp invited Martins to participate in the international group exhibition Le Surrèalisme en 1947 at Galerie Maeght, Paris. On that occasion, the sculptures L’Impossible (1944) and Le chemin; l’ombre; trop longs, trop étroits (1946) were presented. The original edition of the exhibition catalogue, limited to 999 copies (49 of which were signed by Breton and Duchamp), contained 24 original hors-texte prints: twelve black-and-white lithographs, five in colour, two woodcuts, and five etchings. Among the latter was Comme une liane (1946) by Martins, which was given the same prominence as works by historical surrealists such as Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, Jean Arp, and Joan Miró.

It is not surprising that Maria Martins caught Breton’s attention. After all, as the wife of a diplomat (the Ambassador of Brazil in Washington during World War II), she had built her entire career abroad; Martins left Brazil in 1926 and only returned to her homeland in 1950. She held her first solo exhibitions in the United States, where artists like Piet Mondrian, Breton, Duchamp, and Ernst had taken refuge during the war. It was during her third exhibition — a dual show with Mondrian held between March 22 and April 10, 1943, at the Valentine Gallery — that Breton and other artists exiled in America first encountered her work.

In a letter to his friend Benjamin Péret, dated April 19, 1943, Breton wrote, “I recently met again with Maria Martins, the wife of the Brazilian ambassador, who is exhibiting beautiful sculptures of a ‘tropical’ spirit in New York.” He was referring to the artist’s third solo exhibition where, in a turning point in her career, she turned entirely not only toward Brazil but also to a specific region of her homeland — the Amazon. She presented eight sculptures, each based on a character from the region’s mythology: Aioká, Amazonia, Boto, Boiuna, Cobra grande, Iacy, Iemenjá, and Yara. In the same letter, Breton extended his interest to Maria herself, describing her as “an extremely lively and attractive person.” He believed he would certainly have the opportunity to see her again, adding a parenthetical remark that suggested a curious coincidence: “Look at that, she’s calling me. So I was right.”[1]

Besides Breton, at least two other surrealists wrote about the Maria Martins’ work: Péret himself — another member of the movement who participated in the 1947 International Surrealism Exhibition — and the poet Murilo Mendes, one of the leading figures of Brazilian Surrealism, alongside Jorge de Lima. Péret and Murilo contributed texts to the catalogue for Maria Martins’ final solo exhibitions during her lifetime, held at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro in 1956.

If Maria Martins hesitated to identify herself as a Surrealist, the historical Surrealists had no doubt that her work embodied elements aligned with the movement’s vision. But what exactly were these elements? Two stand out in particular. First and foremost is the relationship that Maria Martins established with nature in her work — particularly with the untamed nature of the Amazon jungle. As Breton observed: “It is not difficult to perceive what distinguishes her from all the others, it is the contact with the earth that she fully restores for humanity (a contact that has been lost today, at least for all major human agglomerations), it is the perpetual recourse to the vital sources of nature (of the spirit as well as of the body) that she imposes, it is her constant concern with placing the psychological over the cosmological, opposing the generally predominant tendency that leads humanity down an increasingly dangerous path of sophisms.”[2]

Péret followed the same lines, but went a step further by suggesting that Martins’ struggle with the matter of art would be analogous to that of nature with things (including nature with itself): “Nothing evokes nature’s messages as much as Maria’s work; not because a direct lineage can be imposed between the two, but above all because she acts upon matter somewhat like nature itself.”[3] Murilo Mendes, who was the only one to explicitly mention Surrealism (“the surrealist atmosphere is what interests Maria in fixing”[4]), followed the same direction, highlighting the “magical” nature of her sculptures. “I sought to interpret — though not having seen it in loco — the Amazonian Brazil,” he wrote, “the Brazil of Cobra Norato and certain chorales by Villa-Lobos, where the forces of nature have not yet been dominated by technology, where the flora retains its primitive architectures and the fauna has not yet been tamed, where the magical sense of the land induces man to create signs of hidden understanding.”[5]

Secondly, Breton, Péret, and Mendes saw something visionary in Maria Martins’ work — a foretelling quality that was crucial to Surrealism. On the stairs leading to the upper floor of the exhibition Le Surréalisme en 1947, 21 book covers were arranged to evoke the tarot arcana (excluding The Fool). In his catalogue text, Breton explicated that the intentions behind this new Surrealist collective reflected “a clear desire for anticipation.”[6] For Breton, the Amazon presented by Martins — this part of the “marvellous Brazil,” where “the wing of the unrevealed still hovers” — held “the forces of the future still intact.” He asserted that Brazil, “in the golden eyes and unique vision of Maria, attains the dream of tomorrow in all its enigmas.”[7] For Péret, it was not Brazil, but the world that was at stake: “If antediluvian beings foreshadow today’s fauna, I am not far from thinking that Maria’s sculptures announce a world that does not yet exist — unless it proliferates in other spheres, beyond our sight; but under what skies?”[8]

Murilo, who had published a book of poems in 1941 titled O visionário (The Visionary), also perceived something prophetic in Maria’s sculptures. However — unlike his colleagues, who still preserved a somewhat exotic and optimistic view of Brazil — he saw no hope in them: “The aggressiveness of these forms, projected by the unconscious into a fantastical space often situated beyond Brazil, announces catastrophe, that is, the end of a drama of civilization.”[9] This difference in the perception of the future based on the sculptures (positive for Breton and Péret, negative for Mendes) may be due to the fact that Mendes, like Martins, was Brazilian.

In another passage of that same text, the poet also stated: “We live in a surrealist country. I often say that the borders of logic and psychology end in Brazil. Besides, how else can one decipher, if not through a surrealist code, what has taken place, for example, in recent years in Brazil’s political and economic landscape?” Murilo was writing in 1956, two years after president Getulio Vargas’s suicide, which, to some extent, delayed the military coup by ten years — yet his question, as one would expect from a visionary, remains astonishingly up-to-date.

Written by Veronica Stigger.

[1] André Breton; Benjamin Péret. Correspondance: 1920-1959. Gérard Roche (ed.). Paris: Gallimard, 2017.

[2] André Breton, “Maria”. In: Jean Boghici (org.). Maria Martins. São Paulo: Fundação Luísa e Oscar Americano, 1997, p. 13.

[3] Text by Benjamin Péret for Maria Martins’ exhibition on Museu de Arte Moderna of Rio de Janeiro, in 1956. In: Jean Boghici (org.), Maria Martins cit., p. 31.

[4] Text by Murilo Mendes for Maria Martins’ exhibition on Museu de Arte Moderna of Rio de Janeiro, in 1956. In: Jean Boghici (org.), Maria Martins cit., p. 33.

[5] Text by Murilo Mendes cit., p. 33.

[6] André Breton. “Devant le rideau”. In: Le Surrèalisme en 1947. Paris: Éditions Pierre à Feu, 1947, p. 15.

[7] André Breton, “Maria” cit., p. 13.

[8] Text by Benjamin Péret cit., p. 31.

[9] Text by Murilo Mendes cit., p. 33.