From skyscrapers to space rockets to historic monuments, phallic symbols dominate our visual landscape. But for a society seemingly so obsessed with the penis, sartorial enhancements to the appendage itself are surprisingly rare. While the humble bulge might draw attention in the vice grip of a particularly tight pair of jeans, its sexual allure lies in the power of suggestion rather than the big reveal.

Not so when it comes to the codpiece, a curious phenomenon of sixteenth-century fashion that left little to the imagination. A triangular flap of linen at first, the codpiece was intended to cover the drafty and revealing gap between the two separate pieces of men’s stockings. “Little by little, the codpiece expanded in size, snarl and just-look-at-me ambition,” Michael Glover explains in his potted and informal history of the garment.

Catchily named Thrust: A Spasmodic Pictorial History of the Codpiece in Art, this little gem of a book explores the unique place of the codpiece in visual culture. “Sadly for its admirers, the codpiece was fashionable for a mere half century or so, starting around 1540,” Glover states. From its origins as a gesture of modesty and means of concealing the genitals, it quickly grew into a garment that drew attention and aggrandized them to a ridiculous degree. No longer just a piece of clothing, the codpiece went high fashion.

Easily individualized and decorated with the finest of fabrics, “complete with ribbons and bibbons and other bits of nonsense”, the codpiece was a tool for powerful men to make a statement of their virility and sexual prowess. Glover compares it to the powdered wig and Cuban heel that came later, all equally absurd in their performance of male braggadocio. The codpiece could come in handy, though, doubling for some as a pocket or purse; in one case, a nobleman suspended his spectacles from it when they weren’t in use.

A rich array of paintings by the likes of Titian, Parmigianino and Hans Holbein the Younger are showcased. When displayed together, they are revealed in a startling new light. Frequently eye-popping, with the codpiece as their focus, they bring a welcome sense of light relief and humour to the all-too familiar formal portraits of art history. The fallibility of human ambition and self-presentation is laid bare, like the particularly loud revving of a shiny new sports car.

“The fallibility of human ambition and self-presentation is laid bare, like the particularly loud revving of a shiny new sports car”

A study for a portrait of Henry VIII by Hans Holbein the Younger (the final work was tragically destroyed in a fire) shows him with legs astride and codpiece jutting out. “Solid, steady, sturdy, purposeful, he shows off his magnificent organ of generation in all its cloth-pampered semirotundity,” Glover writes, tongue firmly in cheek. “Above it all there hovers a pretty, nattily tied bow of yielding fabric, as if the king’s genitals were a gift to the fortunate.”

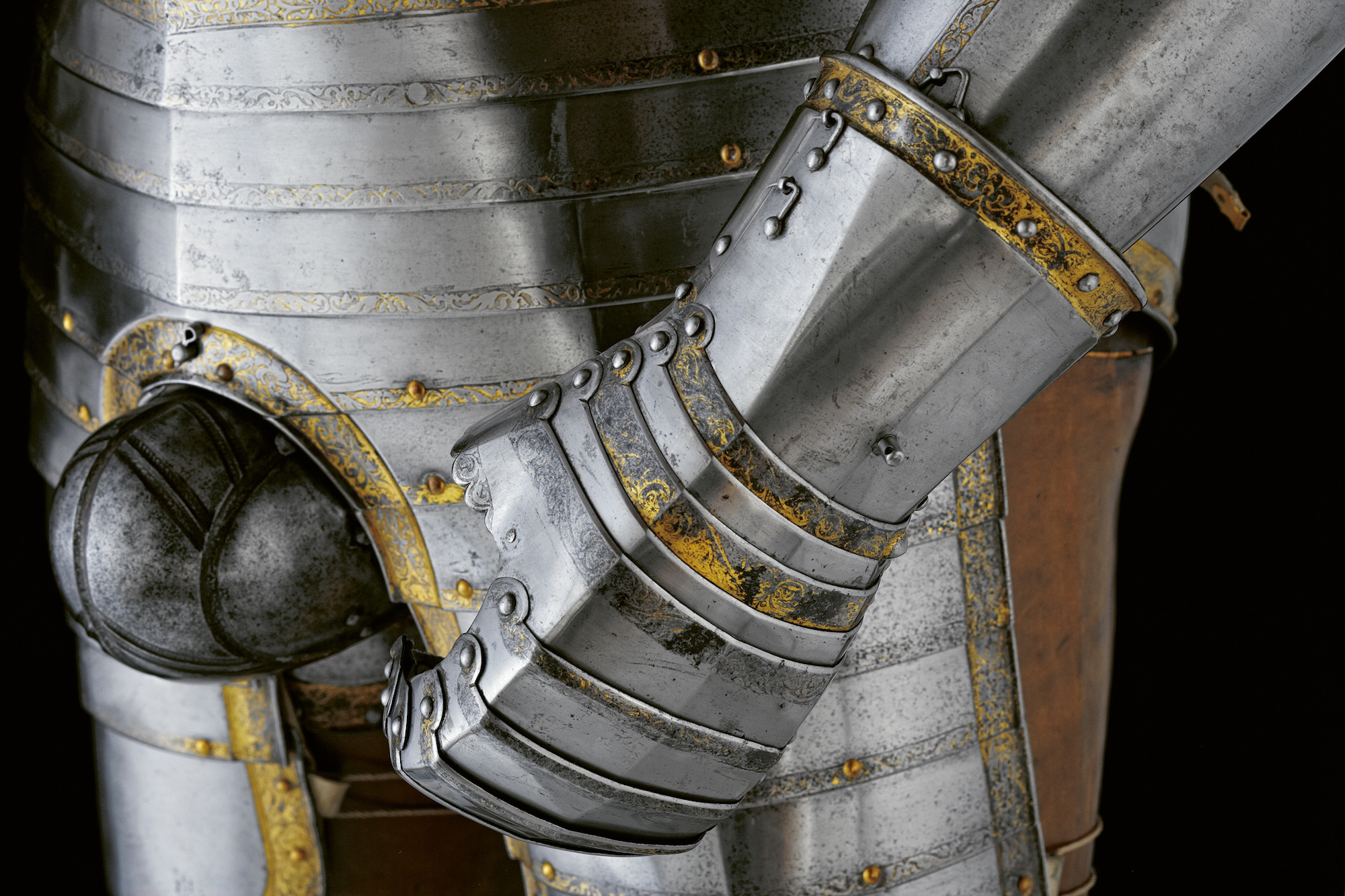

In a raucous painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, a scene far removed from the royal court or privy chamber is shown in full swing. Peasants dance in revelry at a wedding, the codpieces on each male guest unmistakably in view. In another image, a detail of a suit of armour reveals a sizeable bulge. Glover explains that armoured codpieces would have been a familiar sight on the battlefields; this particular specimen belonged to Henry VIII himself, and remains on view at the Tower of London. “As with all other fashionable codpieces of the moment, these metal iterations were exaggerated in size and pugnacious in attitude.”

The codpiece might have sunk from favour almost as quickly as it was embraced by polite society, but its legacy undeniably lives on. Take “crooners and thrusters” like David Bowie, Michael Jackson and Alice Cooper, who have all taken advantage of a well-stuffed crotch. “This time around, it serves to enhance the virile appeal of other kinds of mightily eye-catching men, all equally glitzy in their own fields,” Glover muses.

Malcolm McDowell in A Clockwork Orange is another notable example of the continued relevance of the codpiece in recent popular culture, while Darth Vader and the Stormtroopers in Star Wars surely took style notes from the well-endowed armoury of Henry VIII. Pompous, aggrandising and endlessly erect, the codpiece encapsulates an enduring obsession with the mighty phallus.

Thrust: A Spasmodic Pictorial History of the Codpiece in Art

Published by David Zwirner Books, out now

BUY NOW