“We knocked on the front door of the art world. We rang the doorbell. Ding-dong! They looked through the peephole, they saw who we were and they pretended they weren’t home.” Tim Rollins is speaking with distinctive animation on the final day of Art Basel when I meet with him and K.O.S. (Kids of Survival) members Angel Abreu, Rick Savinon and Logan Swedick in the group’s shared apartment just a street from the fair. “But,” he continues, “we’re smart. So what we did is just go to the back of the building. The door was open and unlocked so we went on in and sat down. And everyone went: ‘Oh, these guys are OK.’ It was very Trojan horse.”

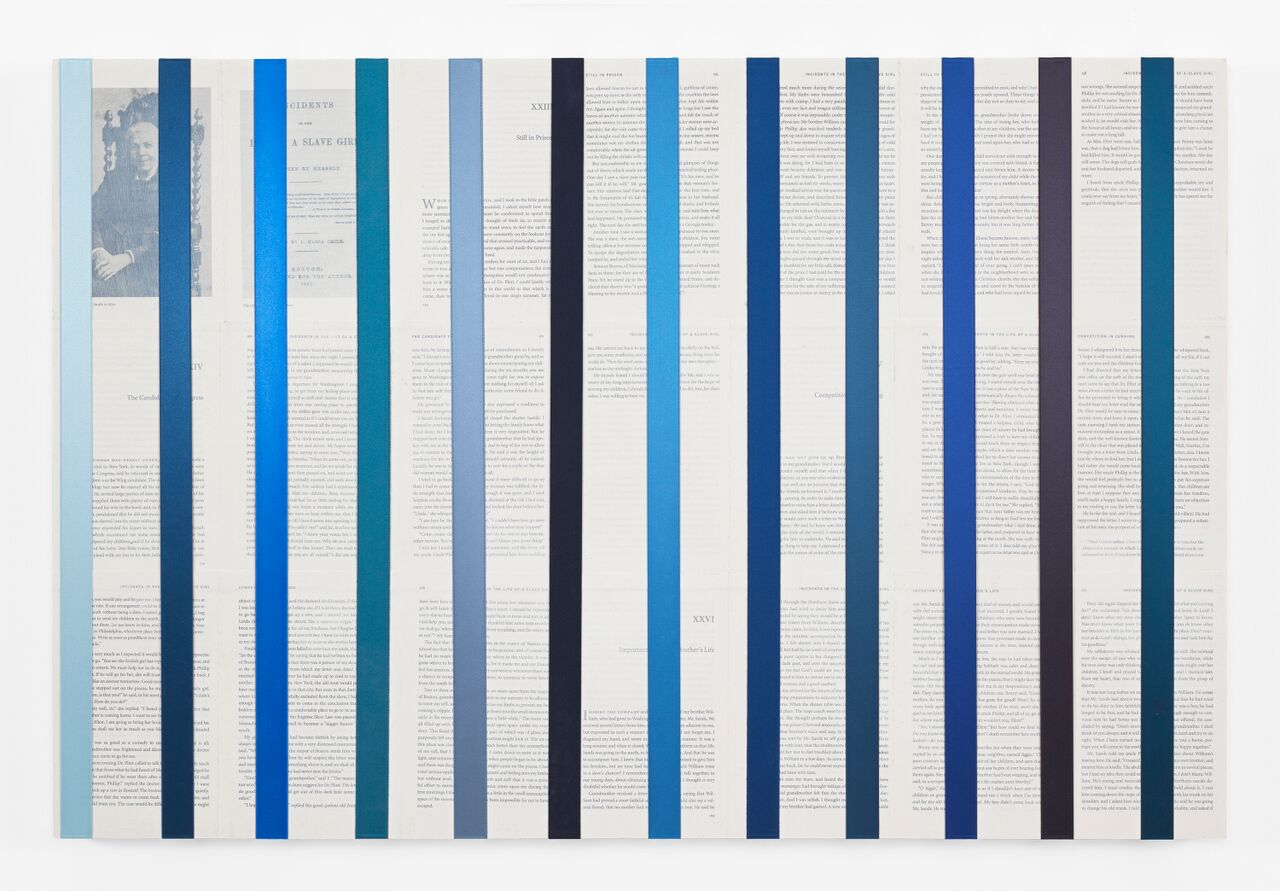

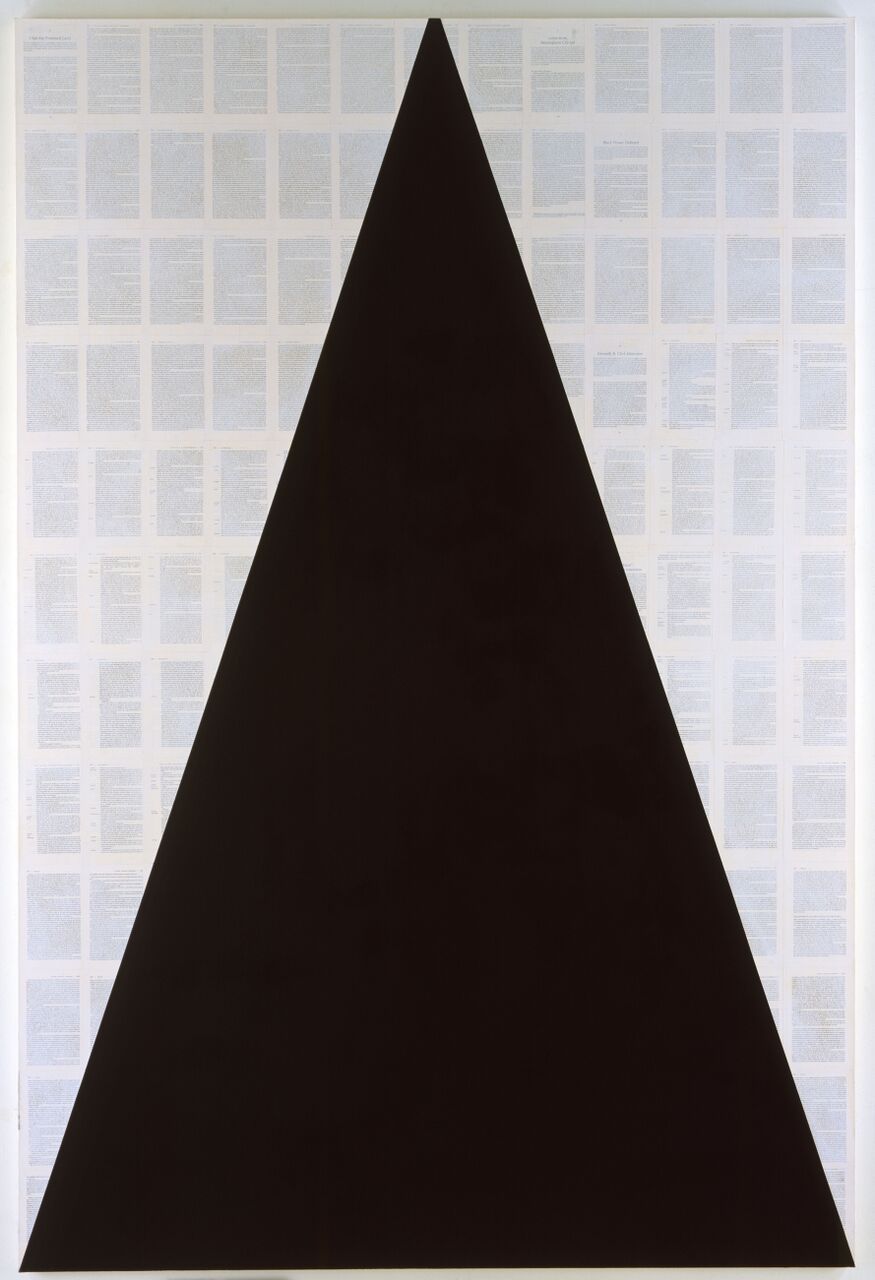

First formed in the early eighties, when Rollins recruited teenage students of the South Bronx school at which he was a temporary teacher, the collective have certainly won artworld acceptance since. Indeed, when we speak they are basking in the inclusion of their Darkwater VI (after W.E.B. Du Bois)—formed using pages of Du Bois’s 1920 book Darkwater: Voices from within the Veil—in Basel’s prestigious and suitably pioneering Unlimited strand. Their work can be found in over 120 public collections including those of MoMA and the Tate. All the same, the journey to acceptance was seen as a little nuts to begin with.

“It was a means to survive: psychologically, emotionally, physically.”

“I remember vividly,” Rollins says of his decision to get the ball rolling, “because I wasn’t meant to stay in that school, I was meant to be there for two weeks and this voice told me: ‘You must stay.’ I’m sorry, I’m not schizophrenic! I’m eccentric but I’m not schizophrenic. The voice said: ‘You’ve got to do this, nobody else is going to do this…’ The reason why I started is: I’ve got to do something, and I’ll worry about it later. I always tell the members they’ve got to get out of the ‘what if, what if, what if’. It should be ‘why not, why not, why not’. It does take courage.”

“I give Tim a lot of courage,” says Savinon, who joined K.O.S. in 1985 and has, but for a one-year hiatus, been a constant presence ever since, “because I look back and in the 80s in the South Bronx it was really rough.”

“A lot of courage and maybe a little bit of stupidity,” Abreu interjects—casual joshing of Rollins is a recurrent theme with these guys, much to his delight. “Maybe a little bit of naivety.”

“Insanity!,” Rollins one-ups. “It was insane.” As he mentions later: “I had to buy toilet paper for my kids when I was teaching. Pencils. I had to bring my own boombox to play my cassette tapes. But we did it. It was a party every day. In terms of the environment it was hellish, but then you had Afrika Bambaataa, you had Zulu Nation. It was the birth of hip-hop. So there was joy. But it was a means to survive: psychologically, emotionally, physically. For real, you didn’t know if you were going to come home that night.”

Today, the collective runs workshops with kids, mainly in the Bronx but also in other cities. (Of an event some years ago in London’s Hammersmith Rollins has the following to say: “We did a workshop with a ragtag group of kids and we made a painting with a young man, which is now in the collection at the Tate. And his name is Steve McQueen. Kiss. My. White. Ass! That’s my ammunition.”)

The work produced often takes its cue from revolutionary texts, as with Darkwater VI. “Du Bois is an extraordinary role model for our young people today because he was not essentialist, he did not believe in categories,” Rollins says of the American educator and civil rights activist. Other titles that have served as an inspiration to the group include Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and Franz Kafka’s Amerika, and the group work with rare first editions. The resulting pieces are often weighty and tactile in appearance, dominated by golds, browns and blacks.

“It’s always worked with K.O.S. and our relationship with Tim, but we give respect and we demand respect,” Abreu says of their work with the fifth to eighth graders who created Darkwater VI. “The way we give respect is by demanding excellence. We’re basically allowing the participants, the young artists, to step up.”

“The refusal of invisibility has always been a major subject of every work we’ve ever made.”

It’s not merely inclusion in the collective that offers a voice to the often unheard and socially excluded, it’s the work itself too. A common thread running through the pieces is the exploration of black history and related texts, as is the literal covering of words on the page with paint and other marks. “It’s a metaphor for how many aspects of culture, particularly for people of colour… they’re not whitewashed, they’re just made invisible,” Rollins tells me. “The refusal of invisibility has always been a major subject of every work we’ve ever made.”

Niclaus of Haguenau and Matthias Grünewald”s Isenheim Altarpiece (1512–16) is also a vital inspiration. As Rollins says: “You can’t deconstruct the mystery of the thing. It’s the joy, it’s the drama, it’s the tragedy.” The piece became hugely significant for the group after Rollins stopped a special ed student, Carlos, from being moved to a class for “educationally mentally retarded children”. Rollins used Carlos’s recreation of the Isenheim Altarpiece on a piece of plywood as evidence of his talents and he ended up going to college. Many K.O.S. members have been to visit the piece in Colmar, France, where it is part of the collection of the Underlinden Museum.

Rollins describes the group as an “amoeba”. While he himself was the original brains behind the operation, and does a fair chunk of the talking, Abreu and Savinon have been fully entrenched since pretty much the beginning, alongside other members including Jorge Abreu, Robert Branch and Ala Ebtekar (twenty-one-year-old Swedick is a recent recruit). All maintain their own practices alongside their work with the collective.

“The workshops serve a dual purpose,” notes Abreu. “It’s not only to keep the ethos of what we do going—because people don’t quite understand now we’re not kids any more—but also as a tool for us to be able to recruit.”

“It’s a terrific story,” says Rollins, “and I get this all the time from stupid people. They go: ‘Tim, what are you trying to prove? Why are you still going to these raggedy neighbourhoods? The social work, the missionary work…’ It drives me crazy.”

The early days were difficult from every perspective. “If you weren’t essentially a white male dude making painting or sculpture it wasn’t considered serious,” Rollins mentions. “I came up with Keith Haring, Basquiat and those folk. I was assistant to Joseph Kosuth. So it was: ‘Oh Tim Rollins, this new hot thing.’ And then they find out you’re working with young people of colour and all of a sudden it devolves from a painting to a mural and an after-school project.” He cites their inclusion in Charles Saatchi’s New York Art Now exhibition as a turning point. “It was exciting, and that’s when we hooked up with Maureen Paley,” he says. “And then we did the Hayward [Doubletake: Collective Memory and Current Art in 1992], which was an extraordinary exhibition. We’ve had wonderful support, particularly in London.”

“We’ve been radically inclusive,” confirms Rollins, “and when you’re radically inclusive you become exclusive to the folk who don’t want to be.” The downright eccentricity of the whole vibe and, yes, the position of Rollins in relation to these odds-beating kids has also given rise to suspicion in some quarters. “It’s a family now and people have a hard time, you know… We’re an alternative family. Some people, some very boring, closed-minded people, have a hard time thinking of it like that. How can these folk love each other? People are so fractious now. I’m a gay man. Clinically bisexual, but I’m a gay man. So it’s a white gay man and Latino…,” he trails off.

“When you’re radically inclusive you become exclusive to the folk who don’t want to be.”

Rollins and K.O.S. are both staunchly professional—polite, engaged, thoughtful—and delightfully personal and real. There is indeed an unapologetic sense of emotion and intensity that feels “other” to the typical public front expected of the art world’s top tier.

As someone who has come of age, and lived a fair chunk of his adult life as part of K.O.S., Savinon perhaps sums it up best: “As a young child I would always take things apart and put them back together. I always thought outside the box from my family members and they always thought I was weird. But when I managed to meet Tim I realized he was thinking outside the box as well. Then I met K.O.S. and Angel, and we were all outsiders within our own groups, our own families, and we made an outsider group together.”

“We have accepted that we’ll always be outsiders,” Rollins agrees. “It’s like a great alternative band or something where you’ve got your folk and your fans and that’s all you need. And it’s so exciting because we’ve only just begun.”

Images courtesy Studio K.O.S. and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

This feature originally appeared in issue 29

BUY ISSUE 29