Textiles have been trivialised too often, limited to the domestic sphere in their narration. Textiles are not quiet, timid, or indifferent to their rich cultural histories. They are sewn, weaved, and woven with a loaded potential, a history that witnesses international and intergenerational exchange. History is a cloth, specifically a patchwork of multiple narrators who start their work at different times, locals, and societies, responding to the topical forms of its creator’s individualised narratives. While these fluctuations in the historical narrative create uncertainty about their honesty, there is an innate truth to textiles that dictates that whichever way they are strung, knotted, warped, or weft, textiles cannot falsely fabricate their cultural weight.

Unravel has been a long time coming, with textiles often being written out of the art historical narrative despite their persistent cultural and political relevancy. Arranged in a series of thematic dialogues, the exhibition examines works from the 1960s to the present day. These themes are ‘Subversive Stitch,’ ‘Fabric of Everyday Life,’ ‘Borderlands,’ ‘Bearing Witness,’ ‘Wound and Repair,’ and ‘Ancestral Threads.’ The term “Subversive Stitch” is borrowed from the title of art historian Rozsika Parker’s 1984 text in which she analyses how textiles have a legacy in the Western Canon of being limited to the feminised spheres of ‘craft’ versus that of ‘fine art,’ and thus dismissed as women’s work. The stitches of Unravel are subversive in that they rebel against their preconceived notions and ideals. Textiles are sites of material history, which record as they are bound in unconventional ways. Just because it doesn’t spell out its intent or witness via written language does not mean it reserves the ability to communicate. Much like fashion, when gendered, textiles are put in tight arenas, bound to only a certain level of social or political agency.

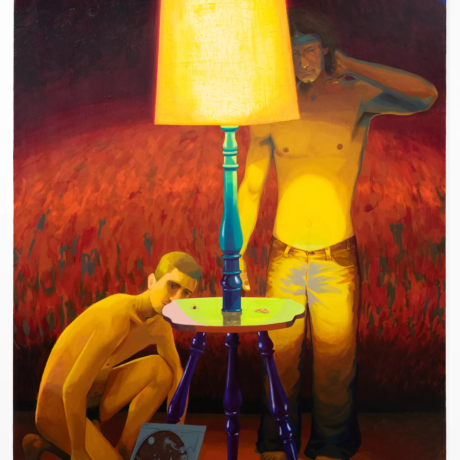

Elephant’s Editor in Chief, Harlem-born Tschabalala Self’s work Koko at the Bodega (2017) features in the ‘Fabric of Everyday Life’ section. The focus of Self’s work is on those who are too often excluded from the art historical canon, much as the medium of the textile has been. In Koko, the Bodega is depicted as the ‘architectural glue, holding together a street corner or an entire block,’ themselves becoming sites for communal exchange. Another line of inquiry in Self’s work is her interrogation of ‘how a body is consumed, how a body is experienced and how a body is inhabited.’ The body depicted is distorted in Self’s presentation as part of this inquiry into the experience of living in a Black woman’s body. Much like the architecture of the Bodega, Black female bodies have been treated as sites encompassed by societies in various ways to further colonial economic progression. Recently, Rhea Dillon exhibited An Alterable Terrain (2023) at the Tate Britain, which followed a similar discourse but from the perspective of the Black British diaspora, being herself British Caribbean. Juxtaposing man-made and natural materials, Dillon’s sculptures act as a conceptual fragmentation of the geographies of a Black woman’s body and the malleable displacement it has undergone through her work. Speaking to Tate Etc, issue 58, 2023, she cites that she aims to “give location’s reins to a black woman, from her body, and with her own hold on her visibility/invisibility”.

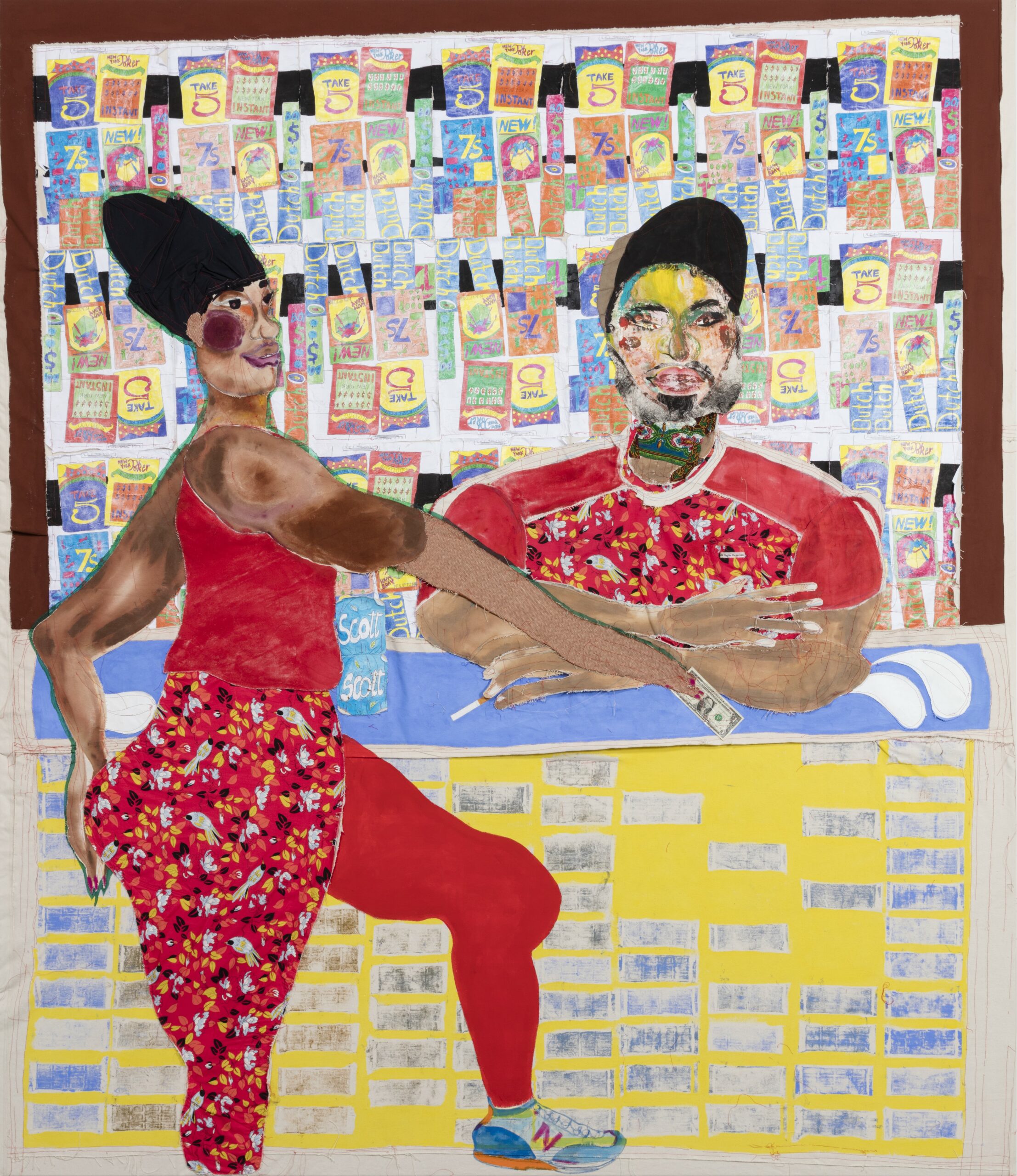

Sites and geographies are intrinsic to the textile narrative, for the textile itself acts as a site, as a location. In Unravel, this shows in the literal display of textile’d geographical maps such as in the work of Filipino artist Cian Dayritt in Yuta Nagi Panaad (Promised Land), 2018 and Valley of Dispossession, 2021, which illustrates the effects of colonisation on the geography of the Philippines. Maps are presented as ‘highly subjective instruments’ to enforce the logic of colonialism.’ Dayritt’s works were informed by workshops held with local communities on the Philippine Island of Mindanao, where the communities have experienced such displacement. Furthermore, Valley of Dispossession reveals how communities and land have been destroyed in Central Luzon through colonial extraction, incorporating QR codes into the material work to display videos, reports and data gathered by human rights groups working in the locale.

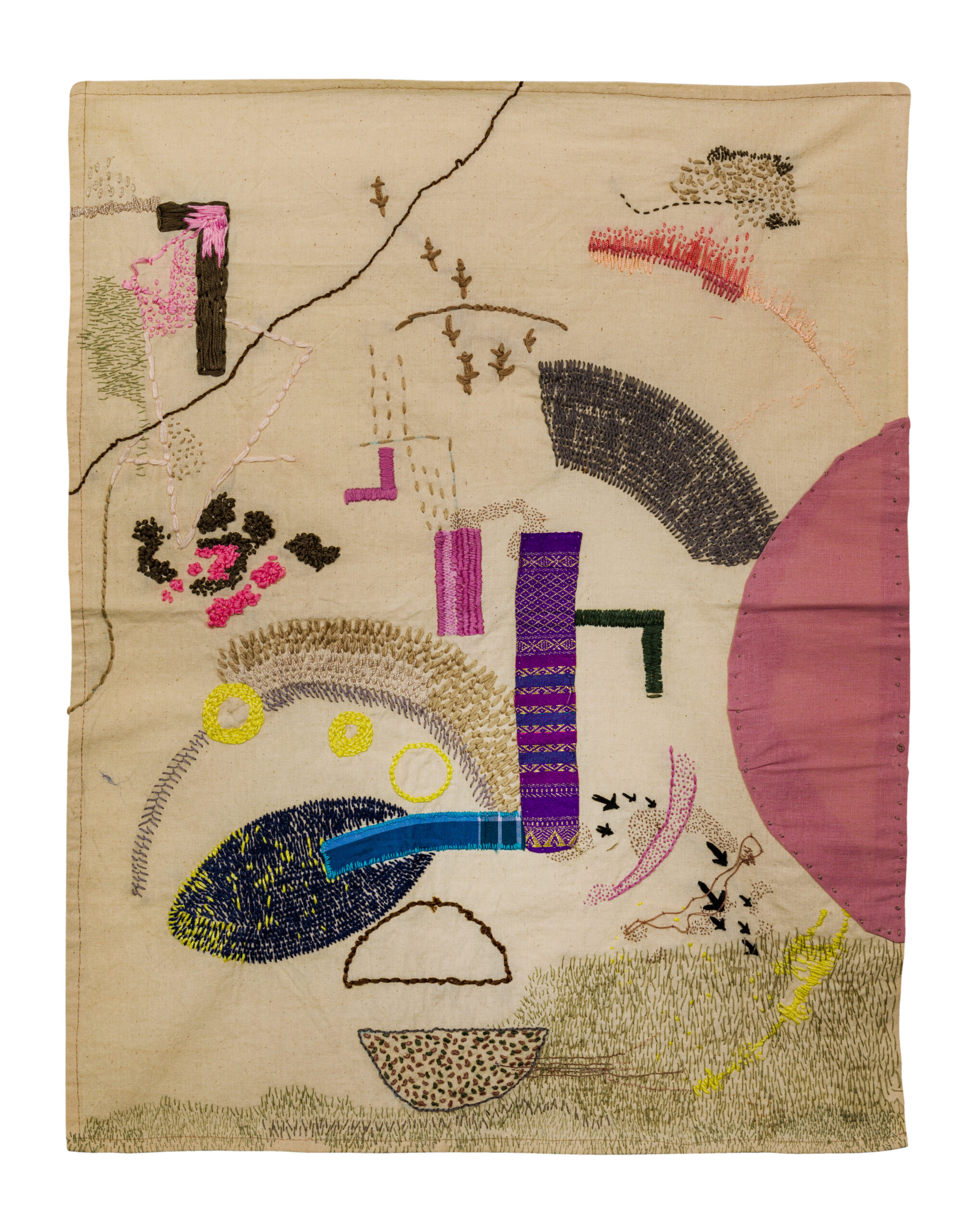

Similarly, T.Vinoja’s Bunker & border, 2021 work embodies an abstracted geography in his handstitched areal landscapes inspired by testimonies of the Sri Lankan Civil War (1983-2009). An all too recent history, the Sri Lankan Civil War has been described as a hidden massacre, claiming over 100,000 people, of which, according to the UN, at least 40,000 were Tamil civilians. The ‘Borderlands’ section in which these works sit borrows from the idea of American scholar Gloria E Anzaldúa. Anzaldúa describes the borderland as a “vague and undetermined place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary.” In this, we can see that the works materialise the artist’s emotions and trauma.

The material weight of heritage is inseparable from textiles, which, in an essentialist way, separates it from fashion. Though fashion can be cut from the same cloth, also having a heavily anthropological, social and cultural dimension, the differentiation lies in that fashion can separate itself from these narratives through its commodification. Textiles cannot. So, when we see someone fashioned in a textile, there is always a message to be unravelled.

Pierre-Antoine Vettorello, a research fellow from the University of Antwerp who specialises in using textiles and garments as a foundation for his artistic narrative, spoke on Louis Vuitton’s appropriation of the Ghanaian Kente cloth, integrating the company’s logo into its design for their January 2021 Menswear show. In his writing, Vettorello highlights that the brand adversities its “savoir-faire” (know-how) when referring to the expertise of its Western atelier yet failed to work with the communities to whom this cloth is local, damaging their profits. When this narrative is unravelled, it reveals that the luxuriation of cultural fabrics can directly damage its communities.

Though the fashioning of a cultural textile can often have this effect, conjuring the question of cultural appropriation versus appreciation, today in London, more than ever, you see the Palestinian’ Keffiyeh’ (كوفية) worn across all bodies. Evan Renfro writes in Stitched Together, Torn Apart: The Keffiyeh as cultural guide, 2017, that “While the keffiyeh began as a mainly utilitarian accessory, good for keeping the sun and dust off one’s face while tending to an olive grove, it soon came to symbolise Palestinian rights.” Since the 1930s, it has fluctuated in its presentation in the West, which at one point saw itself becoming a fashion accessory and at another a symbol of violence against Westerners. Now, it is unmistakably a symbol of Palestinian solidarity.

Unravel is truly important in shedding light on conflicts that have gained nowhere near as much political attention as they should’ve in the West, showcasing chilling histories via the textile medium —loss of life with the absence of bodies. Whilst we cannot always rely on the narrators of history to speak an unprejudiced truth, we can rely on textiles to continually be recording rich histories of peoples, communities and cultures through their fibres.

Written by Lucy Broome