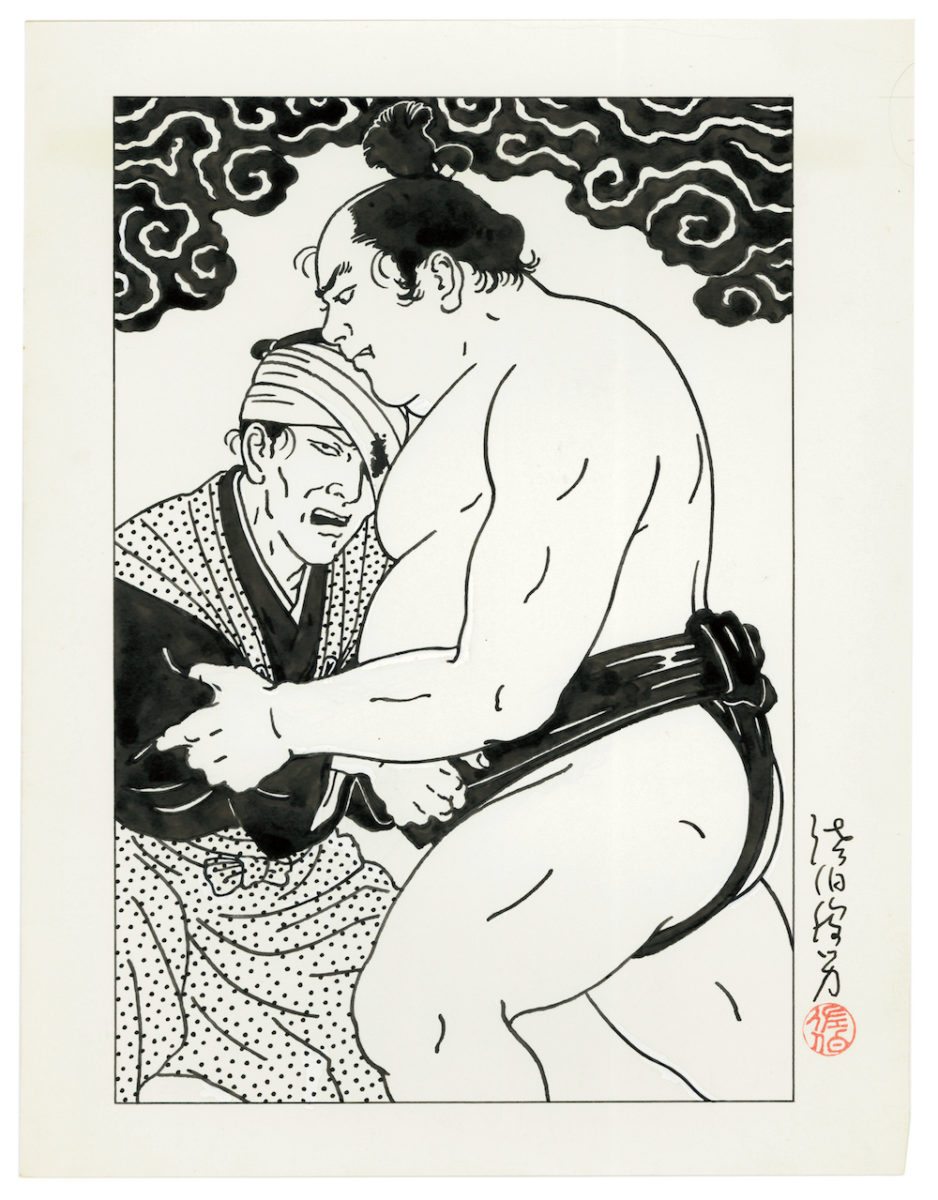

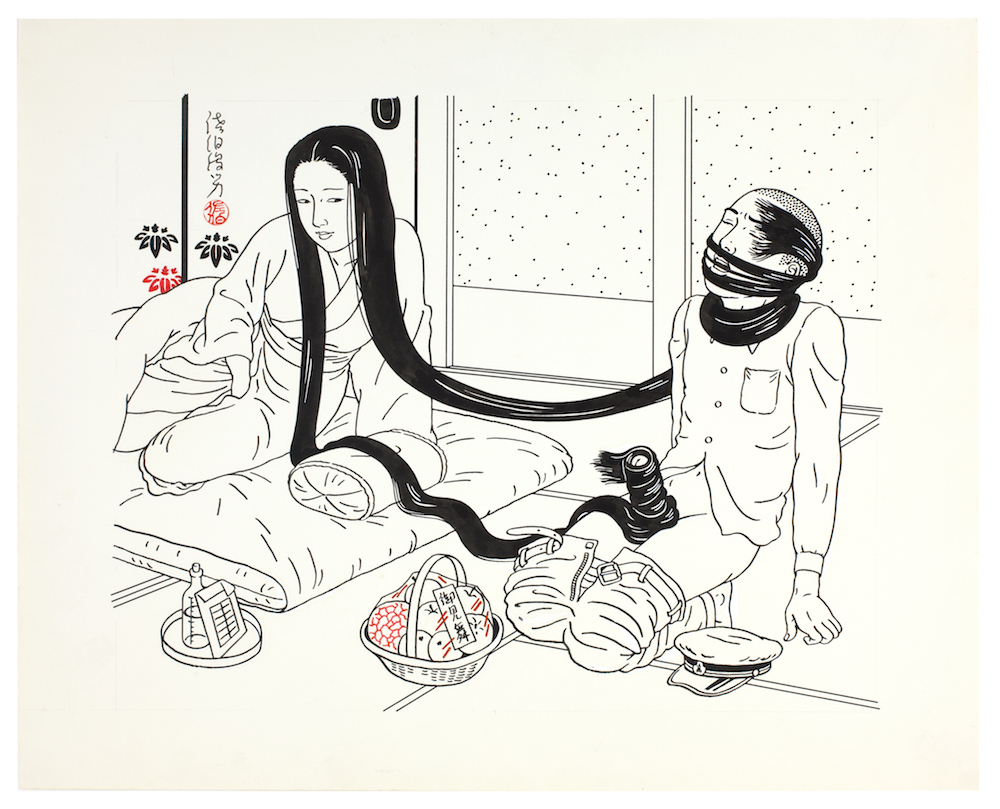

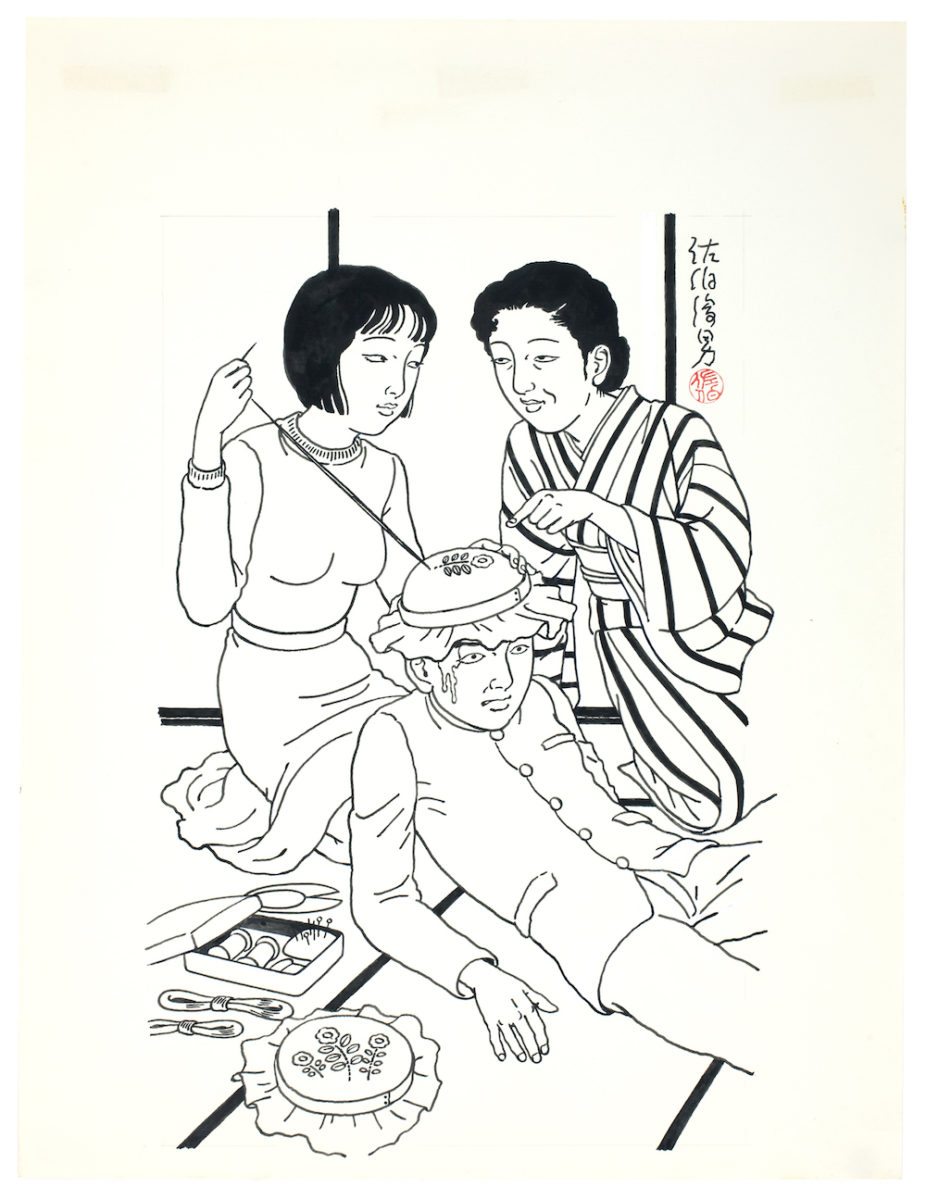

At seventy-something, Toshio Saeki has had plenty of time for sex. As an illustrator for a cult underground BDSM magazine in Japan (as well as a Yakuza gossip rag) in the 1970s and 1980s, Saeki’s sexual imagination has explored almost every kind of sexual dalliance, including transgressive and illegal acts, in ink on paper. There are scenes that even the deep internet couldn’t come up with. (You’ll have to buy one of his books to access those.)

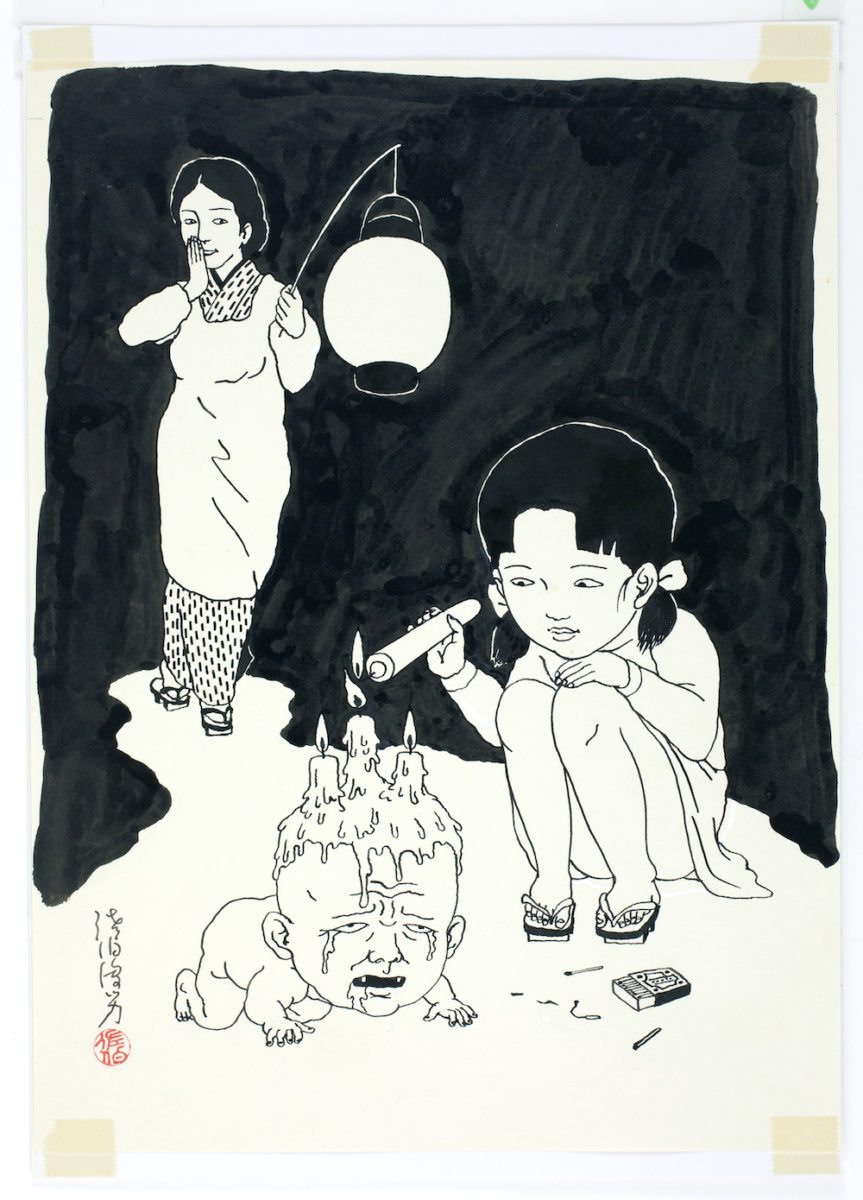

The Japanese artist made a rare public appearance in Tokyo last month at the opening of his new exhibition of old works (at Nanzuka gallery, until 3 March). Murals of some of his seductive prints have been painted on the walls, including one of the artist’s oldest works, created in a small room the artist had rented in 1960. In it, a girl holds an umbrella, on top of which a decapitated head is precariously balanced. Darkness is never far away from innocence. When he sketched the image, it was a breakthrough moment for Saeki, then still young and having recently quit his day job in advertising.

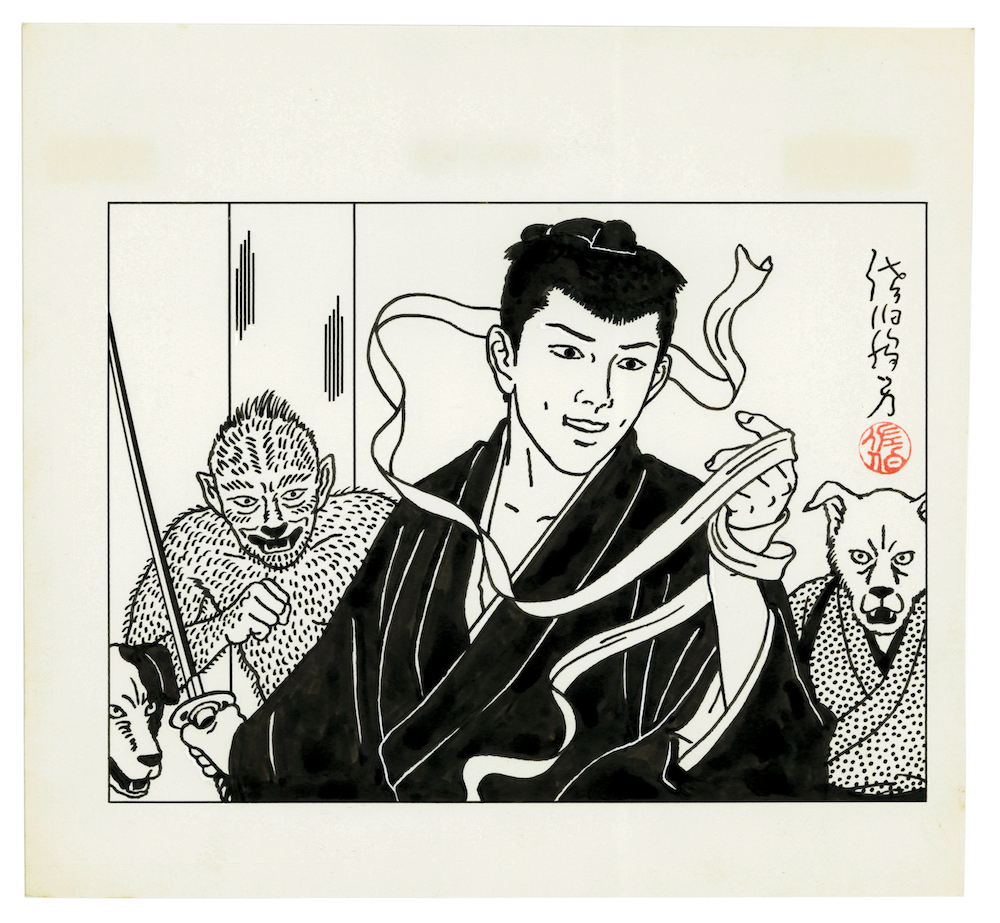

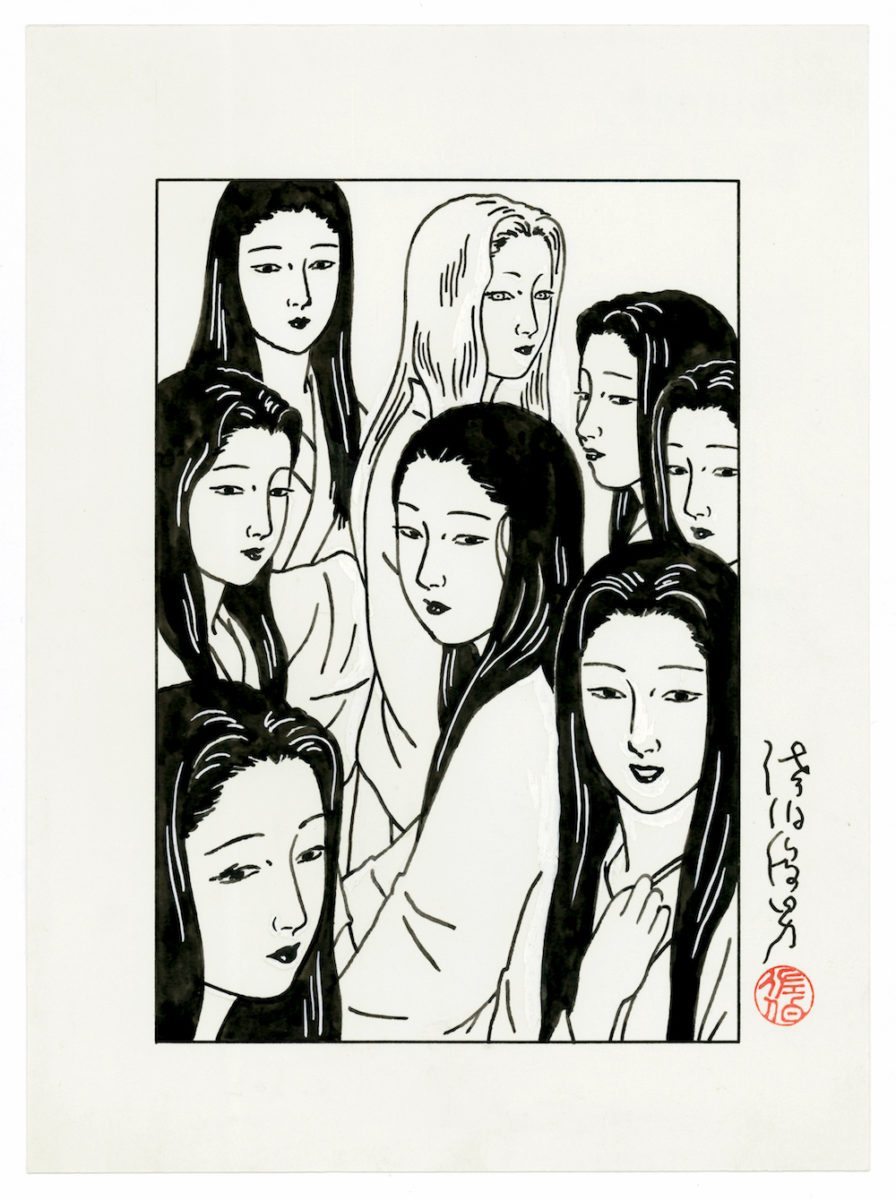

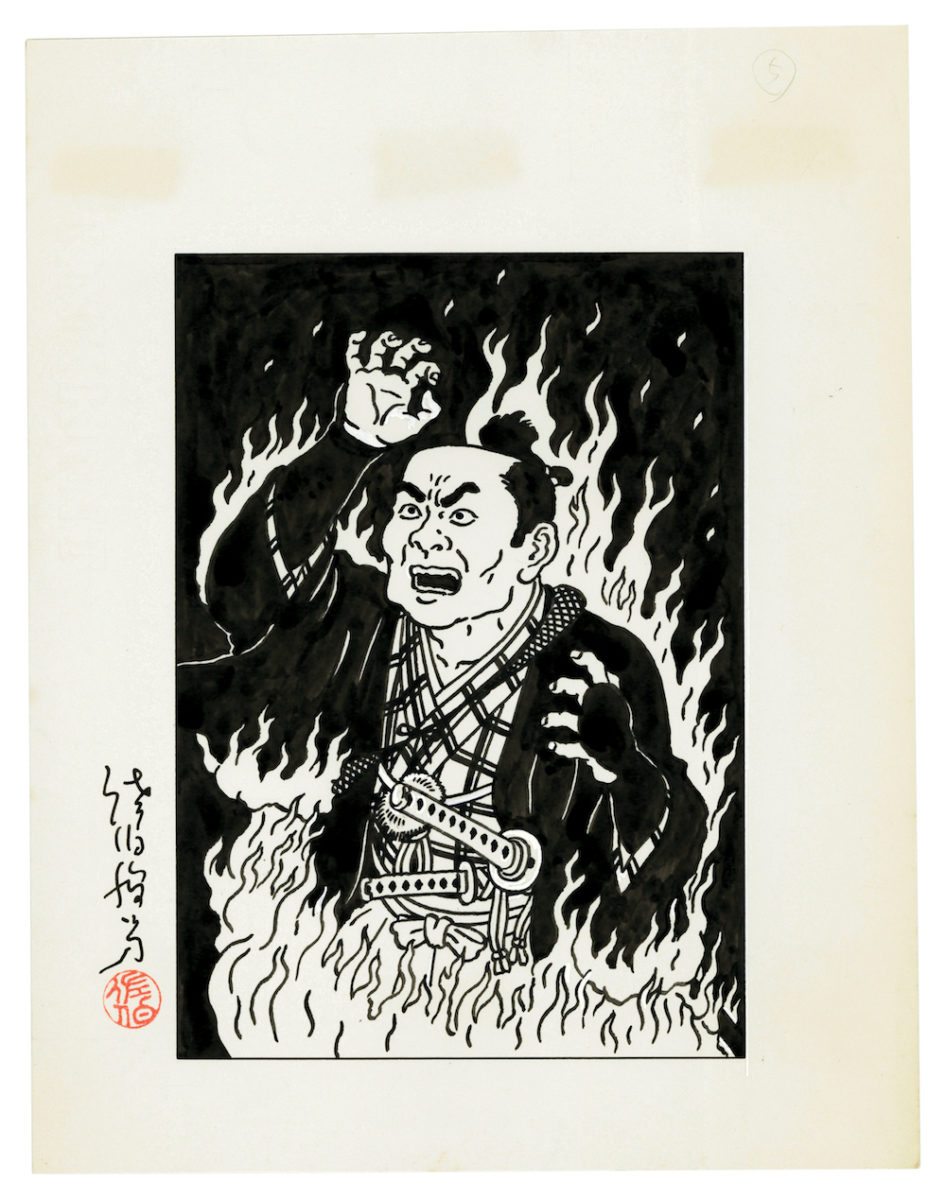

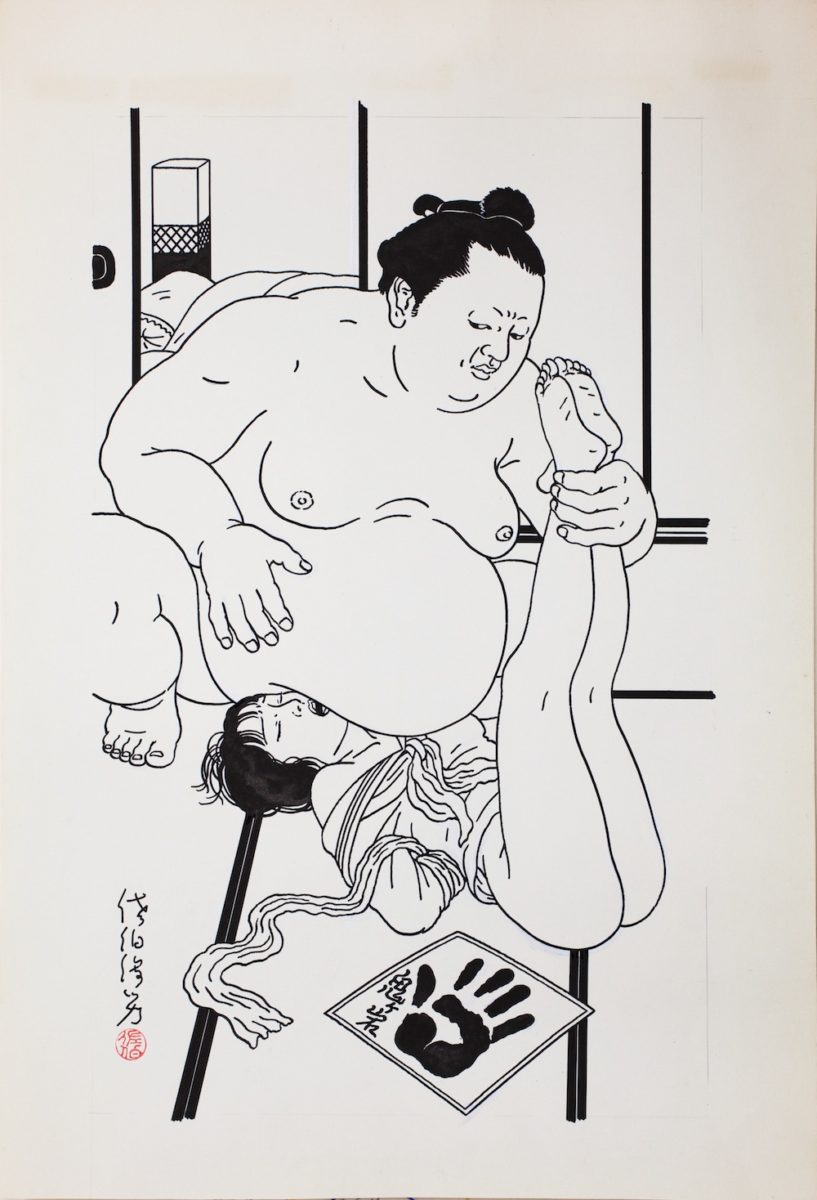

Looking at Saeki’s works—I am currently looking at a sumo wrestler who is forcing his giant mound of belly onto an ecstatic young girl—you could assume many things about where the artist gets his ideas. But there are many surprises when it comes to secretive, shy Saeki. His work isn’t inspired by Shunga, the traditional erotic art of Japan (in fact, he finds it boring). He loves Samurai films; you can see references to various sword-swinging, hirsute characters and the style of movie posters in many of his ink drawings. His work has a fervent feminist following; Yoko Ono is a long-time fan. And perhaps most surprisingly, given the level of depravity in the scenes he depicts, he doesn’t see his works as particularly controversial. I know this because I spent hours sitting on the floor with the artist in his studio, talking about sex. Confronting these works with a western mentality ultimately leads to a dead end.

The other thing is, Saeki doesn’t only draw sex, though, of course, it’s these works that have garnered the most attention and repudiation over the years. Sex represents freedom, fantasy, life and death, and in the realm of fantasy, there are always dark corners full of hidden desires and things you don’t want to see. In truth, it probably doesn’t do much good to probe into Saeki’s subconscious mind—we have enough horrors waiting for us in our own.