This article first appeared in Elephant Issue #38

Tracey Emin does not suffer fools. The infamous artist, who managed the rare feat of crossing over—or smashing into—the mainstream public consciousness as one of the shining stars of the Young British Artists movement, has had more than her fair share of run-ins with the media. As a result, she wastes no time in informing me that basic questions she is sick of answering simply won’t do. It’s an impassioned yet benevolent warning that keeps us on track to discuss her (since concluded) exhibition at White Cube Bermondsey, which brings together an incredible selection of work on a museum survey scale.

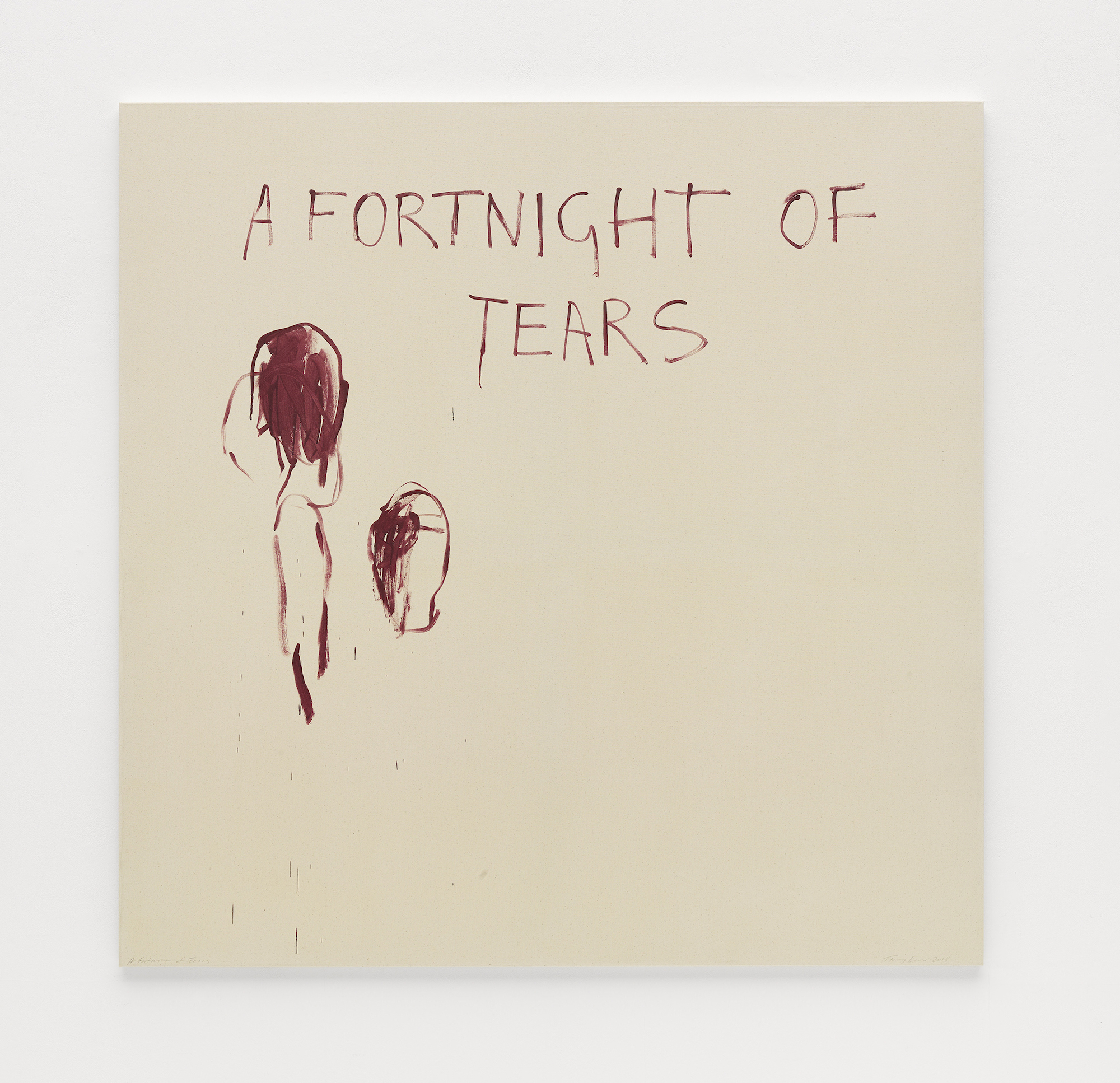

“The show is called a Fortnight of Tears,” she explains. “I wanted to show the beginning and the end of something. So, you’ve got me being pregnant, and then you’ve got my mum dying, and everything in between. When my mum died it was as if part of the world died too. It’s strange how I perceive the world now, it’s different, and that’s partly what the show is about.”

Does the duration, a whole fortnight, hold significance, I wonder? “How long have you cried for before?” she counters. Probably not as long as fourteen days, I’ll admit. “You can’t, you just don’t have enough tears left. You just stop,” she explains. “Then suddenly a big surge of tears come back again. A few times in my life I’ve really cried, uncontrollably, when you go to sleep and wake up crying. That sort of crying is in another league.”

“When my mum died it was as if part of the world died too. It’s strange how I perceive the world now, it’s different”

This kind of intense, raw emotion has always typified Emin’s practice. Her art is defined by her own experience, and she has never shied away from broaching subjects that many would consider taboo. A prime example is How It Feels (1996), a film that covers her experience of abortion in a heartbreakingly candid manner. “That work is twenty-three years old now. It has always been presented on a showreel, but this time it is being presented on its own.” It is a significant choice, not least because Emin has recently seen her forthright interrogations of female sexuality, abuse and mental health reappraised by her critics, in light of the #MeToo era.

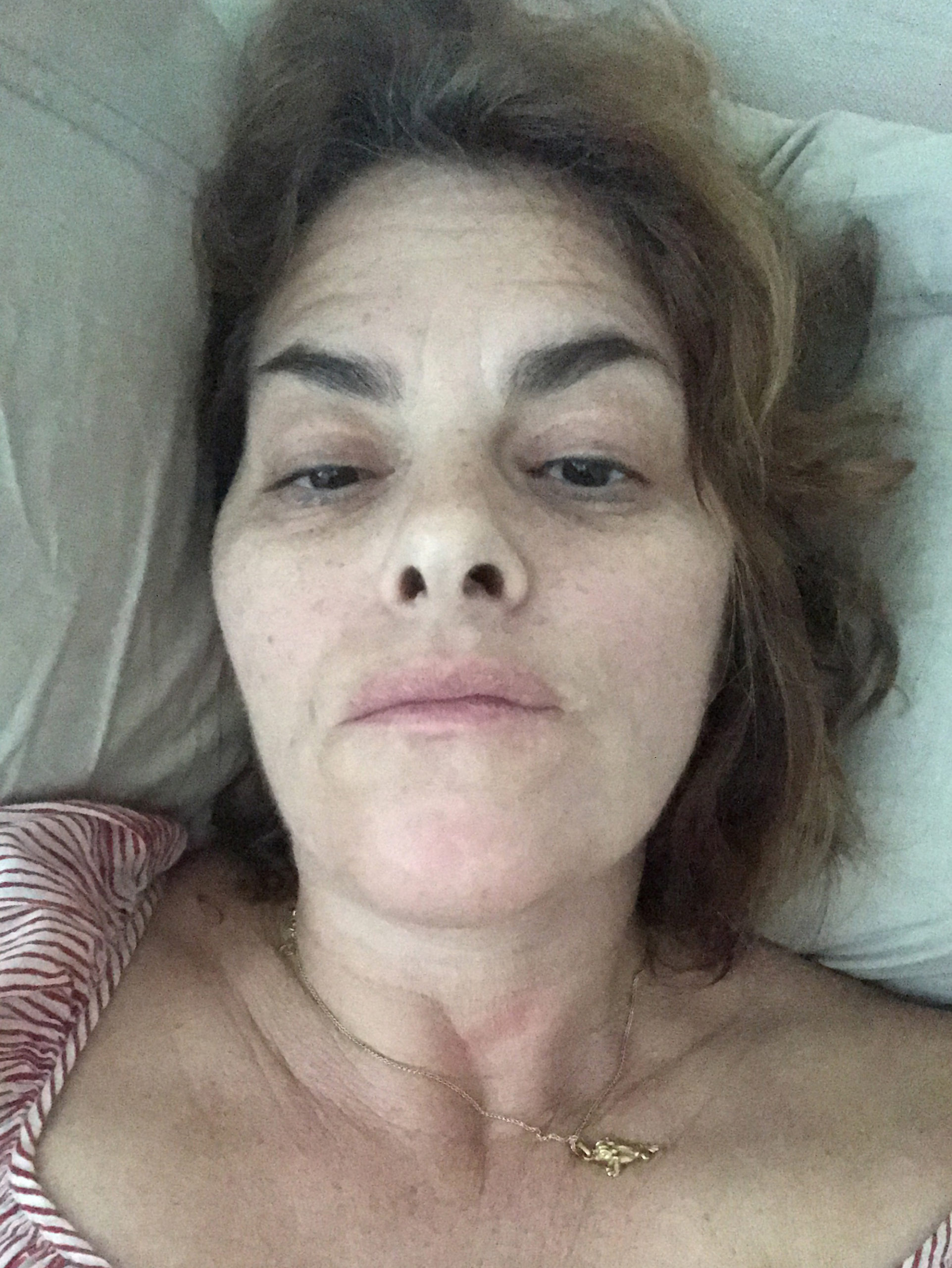

Other forms of intimate introspection take form in a new series of iPhone portraits called Insomnia, which is taken from thousands of images Emin has snapped during sleep-deprived nights. “It’s about looking at myself in my weakest, lowest, physical and mental ebb. I’m looking at myself when I’m too tired to think, and too tired to work, too tired to read, too tired to get up, to run or swim. I’m trapped inside my body, in this cocoon state in bed, and yet I can’t sleep. Anyone who has insomnia knows what I’m talking about.”

“It’s about looking at myself in my weakest, lowest, physical and mental ebb. I’m looking at myself when I’m too tired to think”

While this body of work is based on intense, solitary moments, Emin is also presenting three bronzes, the biggest she has made to date, which naturally involve some element of collaboration in terms of creating “blow-ups” (a full-scale mock-up) and casting the final forms. However, both mediums are rooted in a practice that is informed by following and harnessing emotional instinct. As if to exemplify the point, Emin leads me over to a table covered in a small collection of clay “dolls”, and as we talk she begins to rework a figure, following her intuition to create entirely new forms. “This is me doodling. It’s all tactile. It’s just like painting, you see. This is my hand doing it. That’s what makes it feel good.”

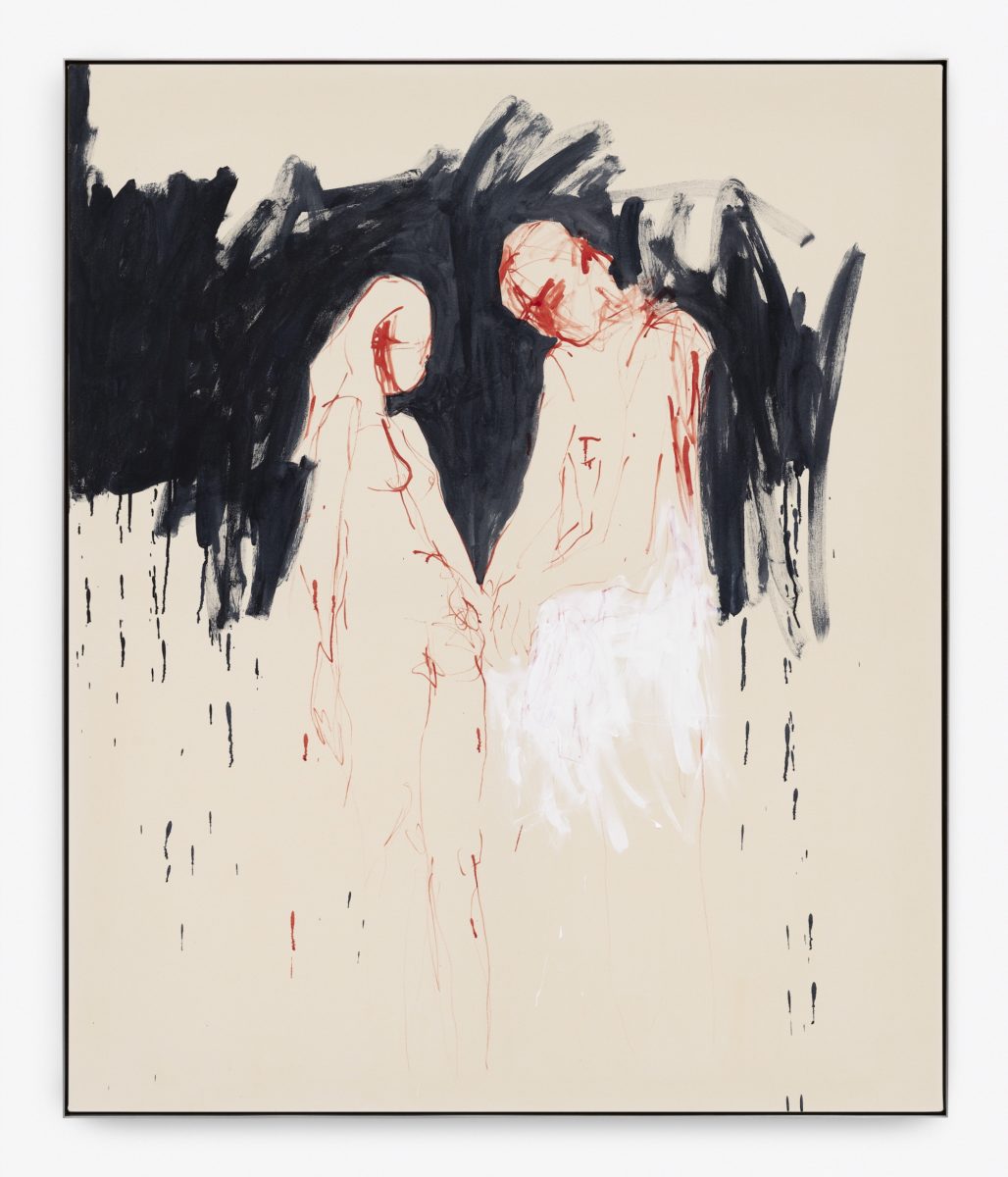

- Left: In The Dead of night I wanted you, 2018. © Tracey Emin. Courtesy White Cube

- Centre: Sometimes There is No Reason, 2018. © Tracey Emin. Courtesy White Cube

- Right: We said Goodbye, 2018. © Tracey Emin. Courtesy White Cube

Emin explains her impulses even more keenly when we discuss painting. She has several canvases hung on the walls, and a much greater quantity have already been packed ready for consideration for the show (she never premeditates the hang, preferring to make decisions once she is in the gallery). As she gestures to various works in progress, she barrels through the physicality and mental fortitude required to produce each piece, as well as the different forms a work might have gone through to reach its current state. While examining one piece she describes the process of drawing, redrawing, overpainting and circling back, as she searches for the meaning, which centres around a female figure in this case: “One minute she looks like she’s been sexually vivacious, then she looks like she’s angry, then like she’s curled up and crying. As I’m drawing, I’m changing it.”

“Even though I really liked it, I thought, does that painting need to exist? It probably doesn’t”

Emin’s fluid—and occasionally frenetic—lines bely her impulsive process, but her practice is often far from rapid. She might overwork, repaint and return to a canvas for days, months or even years, until the piece finally satisfies her. “I’ve always said that if the painting doesn’t tell me something I didn’t know, it’s not very good.” She gestures towards a canvas that has recently been painted white. “That was a blue painting and I really loved it. I just went a bit crazy and kept painting over it, and I shouldn’t have done. But actually, what it was telling me I already knew. So even though I really liked it, I thought, does that painting need to exist? It probably doesn’t.”

- Left: I Wanted To Feel Safe With You, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels

- Centre: I was too young to be carrying your Ashes, 2017-8. © Tracey Emin. Courtesy White Cube

- The Memory of tears, 2018. Courtesy the artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels

I ask if she feels she has lost that painting, or whether its ghost lives on in whatever comes after? “That’s how the history of the painting is made,” she assures me. “But the worst thing is when the stage before was infinitely better than the finished result. If that happens I usually paint over it again.” The emotional fortitude involved in that struggle is occasionally compounded by an innate fear of revealing something too dark to fully explore. “It’s like there’s this weird dialogue going on. Sometimes I paint and draw things and think ‘Fucking hell, that’s heavy,’ and I have to get rid of it. I think ‘Oh my god’, that’s just too much, but it’s still living underneath there.” One has to wonder what these things could possibly be, considering Emin professes that a lot of her new paintings are “really hardcore”, with titles such as Abortion Waiting Room, and many featuring a unifying palette of “bloody, veiny colours.”

“It’s about having an understanding and respect of nature, and knowing that it’s much bigger than yourself”

Considering the intensity of this process, anything that keeps the artist from working would surely be a source of frustration, and I wonder if the hum of activity in her multi-story studio, as well as the streets of East London beyond, are something of a disruption. Unsurprisingly, she views her other studio in rural France as a refuge. “I don’t have any distractions there. I don’t have anything else to do apart from work. I have breakfast, go for a walk, then go to the studio and work non-stop, and everything is good.”

“I rarely paint over things there, and when I do I enjoy it,” she continues. “When I’m here [in London] and I paint over something it’s like I suffer. In France, I might wake up in the middle of the night and think ‘I’ve got to go and paint over that painting, because what if I die or get swallowed up by a hole, and it’s still existing?’ From painting over it I get this tremendous sense of empowerment. That’s the difference. I feel empowered by what I’m doing there because it’s just me in this giant landscape, in this tiny studio.”

“At school we all knew there was this painter called Turner. We heard the stories of him tying himself to a mast and painting a storm—of course he didn’t really—but it was so romantic”

That connection with nature is vital to Emin’s wellbeing. “It’s about having an understanding and respect of nature, and knowing that it’s much bigger than yourself,” she says. “I have to link with that, and if I don’t I tend to feel really low and pretty depressed. I feel like my life isn’t worth living, really.” The sea has also played a crucial role, not only because it was a source of excitement as a child living in Margate, where storms invoked wonder as opposed to fear, but because of its relation to JMW Turner, whose ferocious seascapes depicting that specific coastline irrevocably tied him to the town. “At school we all knew there was this painter called Turner,” Emin explains. “We heard the stories of him tying himself to a mast and painting a storm—of course he didn’t really—but it was so romantic. To grow up with those ideas meant that to be an artist could be wild.”

Wildness is something that Emin is famed for, but her romance less so, which is bizarre considering that her deeply tender neon texts are some of her best-known works. In Margate, for example, the impassioned, melancholic phrase I Never Stopped Loving You lights up the seafront. It’s a phrase that alludes as much to flesh-and-bone lovers as her relationship to her hometown. Likewise, her recent commission at St Pancras station has just had its run extended by several months. The enormous 20-metre sentence I Want My Time With You is a message to Europe, while also alluding to the many meetings and partings that occur at the station.

“It’s actually made from thousands of LEDs, but it appears the same because I know how neon looks and how it should work,” she says. The same obsession with materiality and physicality that is evident in her drawing, painting and sculpting has obviously served her well, because she has taken the time to learn the nuances of this craft, to great effect. “So many people are writing and using text neons these days,” she adds. “But you can’t read a lot of them because they don’t know how to make them properly.”

While Emin takes no issue with people utilising the medium, the string of copy-cats who emulate her handwriting are another thing entirely. “I have so many people ripping me off now, in fact, some makers refuse to take on work that is obviously a copy. They say, ‘We love Tracey Emin, she changed the world of neon!’ At one point it was a really dying industry, but now it is having something of a renaissance. It’s a beautiful material. It makes people happy.”

This article first appeared in Elephant Issue #38

VISIT WEBSITE