“How do you engage someone in the process of reading history and poetry at the same time? Can you bridge policy and poetry?” Tammy Nguyen questions. We are speaking before the opening of the artist’s latest exhibition, A Comedy for Mortals: Purgatorio, at Lehmann Maupin in Cromwell Place, London. Spanning two floors of the gallery space, the exhibition features new paintings, works on paper, and a sculptural art book exploring the complexities of existence. Drawing inspiration from literature, mythology, ecology and history, in this show, Nguyen draws most prominently from Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, which she refers to as a metaphor for the geopolitics of Southeast Asia during the Cold War. The work simultaneously offers a contemporary perspective on life, death, the intersections between geopolitics, and everything in between.

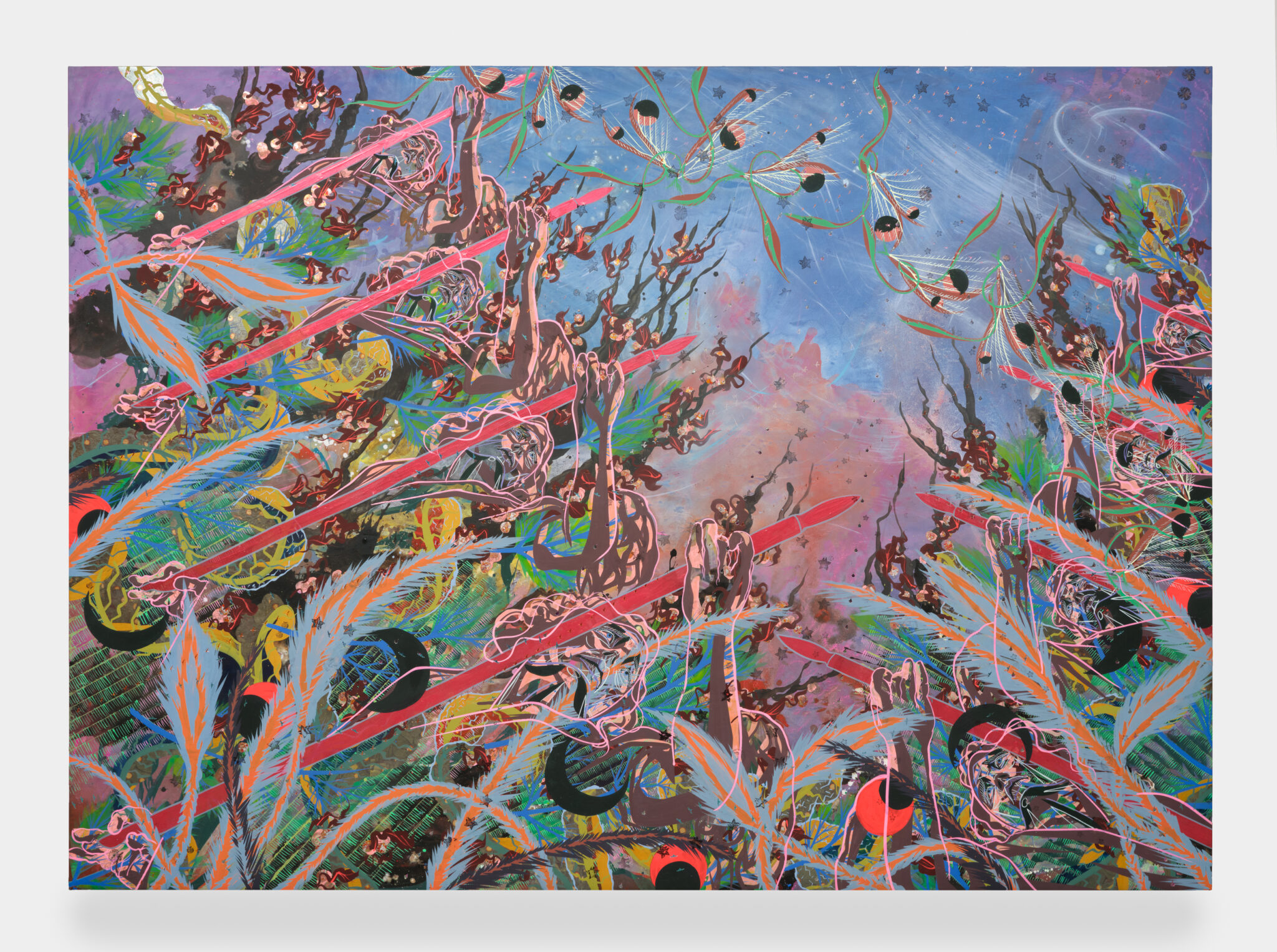

Looking at Nguyen’s work, it is clear that her intention is to collapse spans of scale. I can’t help but think about a quote from The Order of Time by physicist Carlo Rovelli: “In the elementary grammar of things, there is no distinction between ‘cause’ and ‘effect’. The world appears to be cut into pieces, but it is not. The cutting is our own invention.” Cutting and splicing moments from histories and time is Nguyen’s starting point for her work. Using a range of references from her personal history to global events, from Gianlorenzo Bernini’s angels to prehistoric dinosaurs to President Sukarno from the 1955 Bandung Conference in Indonesia, Nguyen explains that she reflects on the turbulent events of recent history. “Before I start working, in the conceptualisation phase, I like to create obstacle courses of different metaphors, and through the process of making, I try to make the metaphors which are embedded with contradiction and things that don’t seem like they should belong together, as harmonious as possible through painting and artist’s books.” In Nguyen’s words, war machines appear as insects, Prehistoric dinosaurs reminiscent of Godzilla, symbolise the continued threat of atomic warfare and serve as a vehicle for addressing past traumas, and Bernini’s angels outside of the Vatican represent the West. Drawing connections between seemingly disparate references serves as a lens through which Nguyen can examine themes of identity, power, and resistance. In turn, through contextualising historical events within a contemporary artistic framework, Nguyen invites viewers to engage with complex geopolitical issues and reflect on the enduring legacies of colonialism and imperialism.

Describing her making process as a process of “ungrounding”, Nguyen works with the panel on the floor in the studio. Her panels are often reversed and rotated during the painting process: the sky ends up at the bottom of the panel below the subjects. Fluorescent paint lines intersect the perspective, ultimately anchoring the subjects onto the canvas surface. Mount Purgatory is aptly located in an in-between space, between night and day, and throughout this exhibition, we see a multitude of different kinds of locations, from sunsets and sunrises to moments when the sun is falling into night. In Natural Love is Always Inerrant, Jesus Christ is arriving by boat to the shores of purgatory, framed by sunset and sunrise. Lunar moths appear as a representation of anti-gravity, described by Nguyen as “the perfect insect to think about purgatory.” They evoke deeper contemplations about the concept of purgatory, the transitional state between earthly life and the afterlife.

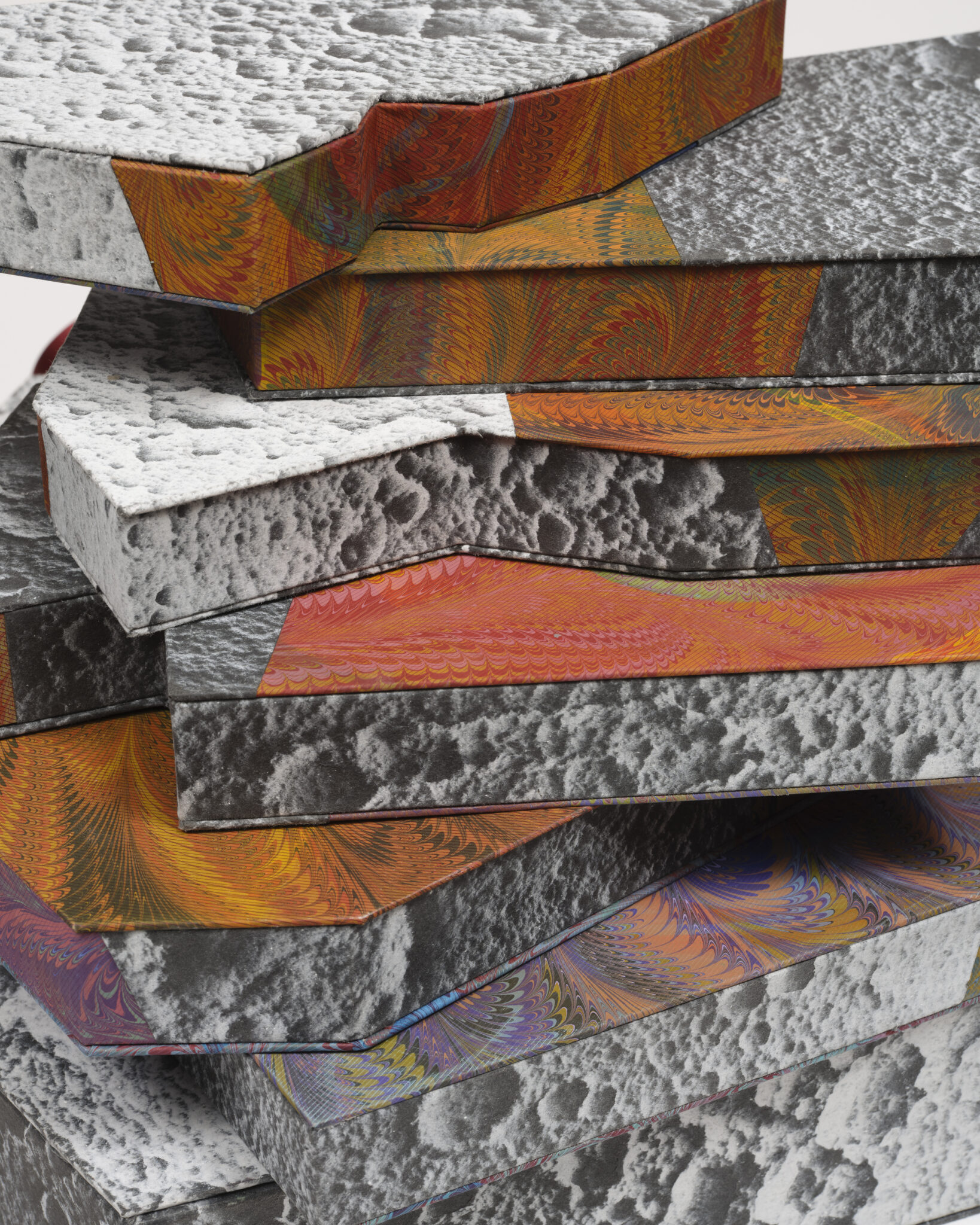

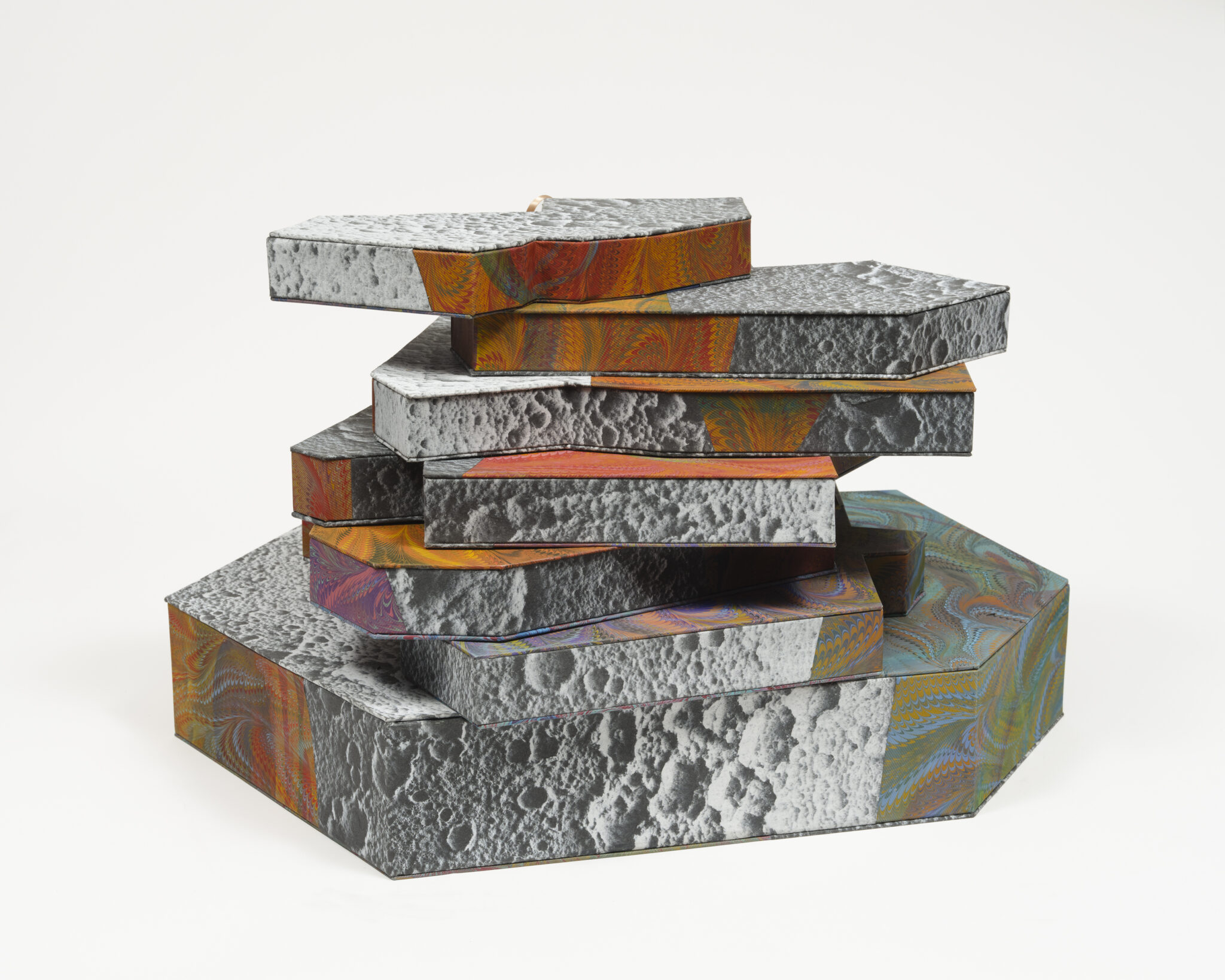

Prior to painting, Nguyen begins with collage. Made up of watercolour, vinyl paint, pastels, screen printing, rubber stamps and gilding, the collages are then scaled up into paintings or referenced in her artist books. Working from different source materials and references, she also works directly from observation with drawings from nature, Angels Carrying Crosses on Mount Purgatory features angels ascending the canvas against a backdrop of luna moths, seashells, and ancient fern fronds: “I like to collect objects and then draw from observation and then through the process of observation, I come up with mark making devices and shapes.” Tammy Nguyen studied printmaking and painting at Cooper Union in New York City and is known for her work in various printmaking techniques, including woodcut, etching, lithography, and screen printing. Working between these different mediums, Nguyen explores diverse perspectives and modes of communication, enriching her practice with new insights and approaches. Through painting, she delves into the tactile exploration of colour, texture, and form, while collage allows for the layering and juxtaposition of images to create complex narratives. In her artist books, Nguyen experiments with order and sequencing, challenging conventional ways of understanding and inviting viewers to engage with her work.

“Confusion is my North Star,” she explains. When I ask her about the repeating of some of the world crises that are taking place in the world right now, Nguyen explains that she has “been humbled by a lot of historical events that have happened locally and globally… I’m just so struck and just totally confused in some ways.” This sense of confusion and introspection is palpable throughout the exhibition, inviting viewers to confront their own uncertainties and existential dilemmas. A painterly method of finding order amongst the chaos is her form of repetition and symbolism. Nguyen explains, “An icon repeated over and over again can mean something different, when it’s a different colour, when it takes on mass, or when it’s used as an element of another thing.” This repetition serves as a metaphor for the cyclical nature of existence, where patterns and symbols take on new meanings as they evolve and transform.

The use of simple shapes and symbols is another prominent theme in Nguyen’s work. She elaborates, “The circle begins as an opening, the circle is a passageway, it’s also a kind of multiplicity that collapses into a single shape.” Through these simple yet impactful forms, Nguyen explores world-building and the interconnectedness of all things.

By juxtaposing imagery from The Bandung Conference, which brought together twenty-nine African-Asian nations in 1955, denouncing colonialism and an aspiration for a new world order, with elements from Dante’s Divine Comedy and other sources, Nguyen creates a rich tapestry of meaning that speaks to the universal human experience. “Already, the imagery of Dante and Virgil arriving on the shore speaks to ideas of migration and refugees in the case of my own personal history. This becomes like the starting point for me to kind of expand and build this world or just my version of purgatory.” Nguyen’s parents immigrated to the United States as refugees following the withdrawal of the American military from Vietnam in 1975. “In thinking about purgatory, I wanted to compare Mount Purgatory, which is what Dante imagines, so I’m something else in history that is related to my diasporic story, things that I nd that are urgent today. Today, I’ve gravitated towards a lot of historical events during the Cold War.” In Nguyen’s work, history often serves as a touchstone of the past, grounding her exploration of identity, memory, and collective experience. Reimagining and interrogating historical narratives illuminates their relevance to contemporary society and individual lives. By incorporating excerpts from The Bandung Conference speeches and referencing its ideals of solidarity and independence, Nguyen explores the ways in which language shapes identity and history. She poses questions about the possibility of bridging policy and poetry, diplomacy and art, inviting viewers to contemplate the intertwined nature of political and cultural narratives. Moreover, the Bandung Conference represents a broader theme of global interconnectedness and the struggle for self-determination. In this respect, the work explores the complexities of cultural exchange, migration, and diaspora, reflecting on her own personal history and the experiences of marginalised communities.

In Dante’s Purgatorio, Dante and his guide Virgil ascend Mount Purgatory. The journey unfolds across seven terraces, each dedicated to a specific deadly sin, where souls undergo penance related to their transgressions. “Something that I was really excited to think about was to question: what if the idea that Purgatory and mountains are formations that come to us in the present, but they arrived to us from an ancient time that is very difficult to understand.” Nguyen explains, “For instance, when you go to a museum, and you see an artefact, and it says, from 200 million years ago, this is so abstract, right? I wanted to really bring that type of abstraction into this, considering the context of the show.” Positioned at the base of the book, a golden cast of a dinosaur’s footprint anchors the narrative in a primordial past, inviting contemplation of the passage of time and the enduring legacy of prehistoric creatures. Its placement at the foundation of the book metaphorically suggests a grounding force, perhaps indicating a connection to the earth and the cyclical nature of existence.

Throughout the exhibition, Nguyen references the anxieties of the Cold War era, including the looming threat of conflict and the struggle for sovereignty in Southeast Asian countries. As viewers navigate through A Comedy for Mortals: Purgatorio, they are confronted with questions of mortality, morality, and the nature of existence itself. Nguyen prompts us to consider our place in the world and our responsibilities as global citizens in an ever-changing geopolitical landscape.

Written by Sofia Hallström

A Comedy for Mortals: Purgatorio at Lehmann Maupin, London runs until 20 April. The final part three of her Divine Comedy series will be presented at Lehmann Maupin New York in Spring/Summer 2025. Tammy Nguyen will have an exhibition at the Sarasota Museum of Art in Florida, 2024.