Tyson Reeder likes his paint thin. His works are often so diaphanous that they appear to glow from within. “Thin painting,” he says over Zoom, “is kind of a high-wire act. There’s no concealment. It’s a vulnerable surface.”

Reeder’s 2019 landscape Autobahn is a case in point. Dainty, satin-toned motorbikes wend along a winding road. Phosphorescent palms in pink, green and leopard print obscure a turquoise sea. The white of the canvas shines through the meagrely applied paint. Reeder’s psychedelic dreamscape defies the rigidity of its title. Despite appearances, there is an order to the Chicago-based artist’s works. “Most of my paintings build on a landscape armature, these very simple, dumb horizon lines, anchored in a kind of location,” he explains. “Then you can plug in anything.”

- Tyson Reeder, Autobahn, 2019. Courtesy the artist

Recurring plugged-in elements include palm trees, bikes, cars, elevated highways and block-like buildings. Sometimes, Reeder cribs from sources both high and low. Autobahn owes its composition to a Milton Avery landscape. The leopard-spotted trees were taken from a textile, while the motorcycles came from a magazine. Reeder stitches these elements into something new, like a Matisse cut-out without the scissors.

“I was in this rural situation, just painting, distancing, not seeing anybody. The last thing I was thinking about was an international collaboration”

Autobahn has now itself been borrowed, courtesy of Celine and its creative director Hedi Slimane. For the Parisian couture house’s spring/summer 2021 menswear collection, The Dancing Kid, Slimane drew inspiration from youth culture during the past year: a time of casual home dressing, viral TikTok crazes and hope for a post-lockdown future. As part of that collection, Celine has released a suite of lightweight pieces (a windbreaker, a coach jacket, a hooded sweatshirt, a Haitian shirt, a T-shirt, a pair of shorts and a bucket hat) adorned with Reeder’s painting.

Few have bridged art and fashion as adroitly as Slimane, himself a photographer and curator. Since taking the helm at Celine in 2018, he has brought contemporary art into the brand’s garments and boutiques. In 2019, he set up the Celine Art Project, which drafts in contemporary artists to exhibit site-specific works in Celine stores.

The same year, he began a series of collaborations, the first wave of which included wallets and rucksacks printed with an enigmatic eye-and-lips motif by American painter Anneli Sanaye Henriksson, while 2020’s four projects included jackets and shoes emblazoned with texts by the Brooklyn artist David Kramer. The Dancing Kid has the most expansive collaborations to date: as well as Reeder, it adapts works by Gregory Edwards, Ryan Ford, Jesse Harris, Amy Sillman, and the collective Turpentine.

Reeder’s participation began last summer as Covid-19 raged across the American heartland. He had absconded to an industrial building owned by his brother (and fellow artist) Scott in the Michigan countryside. “I was in this rural situation,” recalls Reeder, “just painting, distancing, not seeing anybody. The last thing I was thinking about was an international collaboration.” Celine got in touch through Canada, Reeder’s New York gallery. “They’d seen my work at the Independent Art Fair in Tribeca a few years back, and were interested in it,” he recalls. The resulting team-up was entirely remote, due to the pandemic. “I couldn’t sit down with Hedi or Celine, but there was a lot of back and forth. I would get these emails showing beautiful things from the atelier in Paris.”

“I started making very small works with fabric dye on index cards. That got me back into my love of painting”

Though artist and designer collaborated from far-flung locations, their work shares an imaginative affinity. With their abundant palm trees, infinite horizons and winding coastal freeways, Reeder’s paintings unmistakably inhabit an imagined California, the most mythologised of American landscapes.

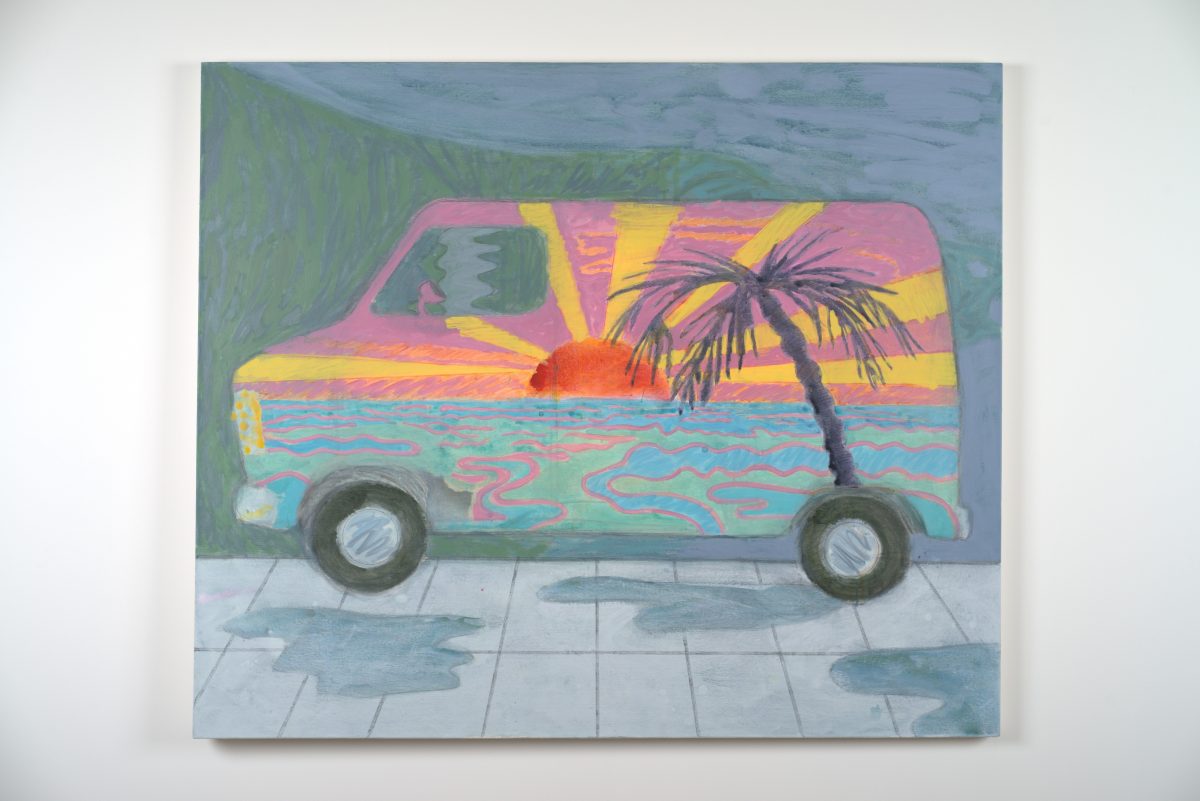

- Tyson Reeder, Sunset Van, 2014. Courtesy the artist

In Sunset Van (2014), we see a truck on a damp road, which has been decorated with a perfect Pacific idyll. “I’m interested in the mediated vision of this tropical stuff: the idyllic, tropical sunset on a van in Chicago, rather than the tropical sunset itself,” says Reeder. Slimane has long been concerned with the West Coast mythos. In 2011, the designer curated California Dreamin (a group show exploring the mythos of LA) at Galerie Almine Rech’s Parisian outpost. A year later, while appointed director of Saint Laurent, he uprooted the brand to the City of Angels.

The Dancing Kid is not Reeder’s first brush with fashion. “When I was younger, I loved the Vivienne Westwood clothes with Keith Haring,” he says, “and they still look great to me.” Dick Hebdige’s classic volume Subculture: The Meaning of Style (1979), about punk and its contemporaries, was an early influence. Reeder has even tried his own hand at design: when he first started exhibiting in New York in the early 2000s, he would wear his own sneakers. “I made them out old tennis shoes,” he remembers, “and drew lions on them. They would fall apart.”

Collaborations both inside and outside art have been a cornerstone of Reeder’s activities from the start. After studies at ArtCenter College of Design in the LA satellite Pasadena, he moved to Milwaukee, an industrial city in the Midwest. “I had a bit of the post-graduate ‘fuck art’ type of thing, where I wasn’t excited about what was going on,” he admits. There, he worked with the filmmaker Chris Smith, best known for his documentaries American Movie (1999) and Fyre (2019), to produce online videos. “We made all sorts of content,” recalls Reeder. “We had this soap opera called Milwaukee… It was before YouTube, so we were a little too early. Someone should have made a reality TV show about a bunch of artists with these huge clunky computers, composing vides.”

“A lot of curating is based on canonising or tidying up. I like it when it’s the beginning of an experiment”

After that project “hit a wall”, Reeder returned to painting. He initially used materials from the local drugstore. “I started making very small works with fabric dye on index cards,” he explains. Reeder sent his paintings to a friend’s apartment gallery in New York, stuffed into envelopes: the subsequent exhibition launched his career as an artist. “That got me back into my love of painting,” he tells me. “Then I found my little peer group of artists.”

One of these peers is his brother Scott, with whom Reeder has worked on various curatorial projects, often with an anarchic, absurdist bent. They ran a gallery named General Store for three years. The Dark Fair, held in Milwaukee and Cologne, saw artists exhibit works that could be seen in pitch darkness; the infamous group show Drunk vs Stoned at Gavin Brown’s Passerby in New York included work that reflected either state. “We had another show,” Reeder recounts, “with these cheap four-colour Bic pens, and you had to draw something with them.” He is currently running Bubbles: a miniature gallery hosted within his studio aquarium, featuring waterproof work submitted by artists. “A lot of curating is based on canonising or tidying up,” he explains. “I like it when it’s the beginning of an experiment.”

Working with Celine has been an experiment too. And for Reeder, it has been a rewarding one. “It’s been so fun that I want to work with fabric, to make a dress,” he says, “and it has already changed how I want to paint: it makes me want to simplify my imagery even more.” Although he has not yet seen the garments in person, he has in photograph and film. “Some of the simpler forms really pop on these jackets, like the yellow palm trees,” he says. Transplanted onto lightweight material and worn by moving bodies, Autobahn’s landscape is abstracted further, into shimmering, kinetic patterns. “It was amazing to see how the colours translate.” One test remains: would Reeder wear the garments covered in his own work? “I would love that,” he tells me. “I have no shame about that.”