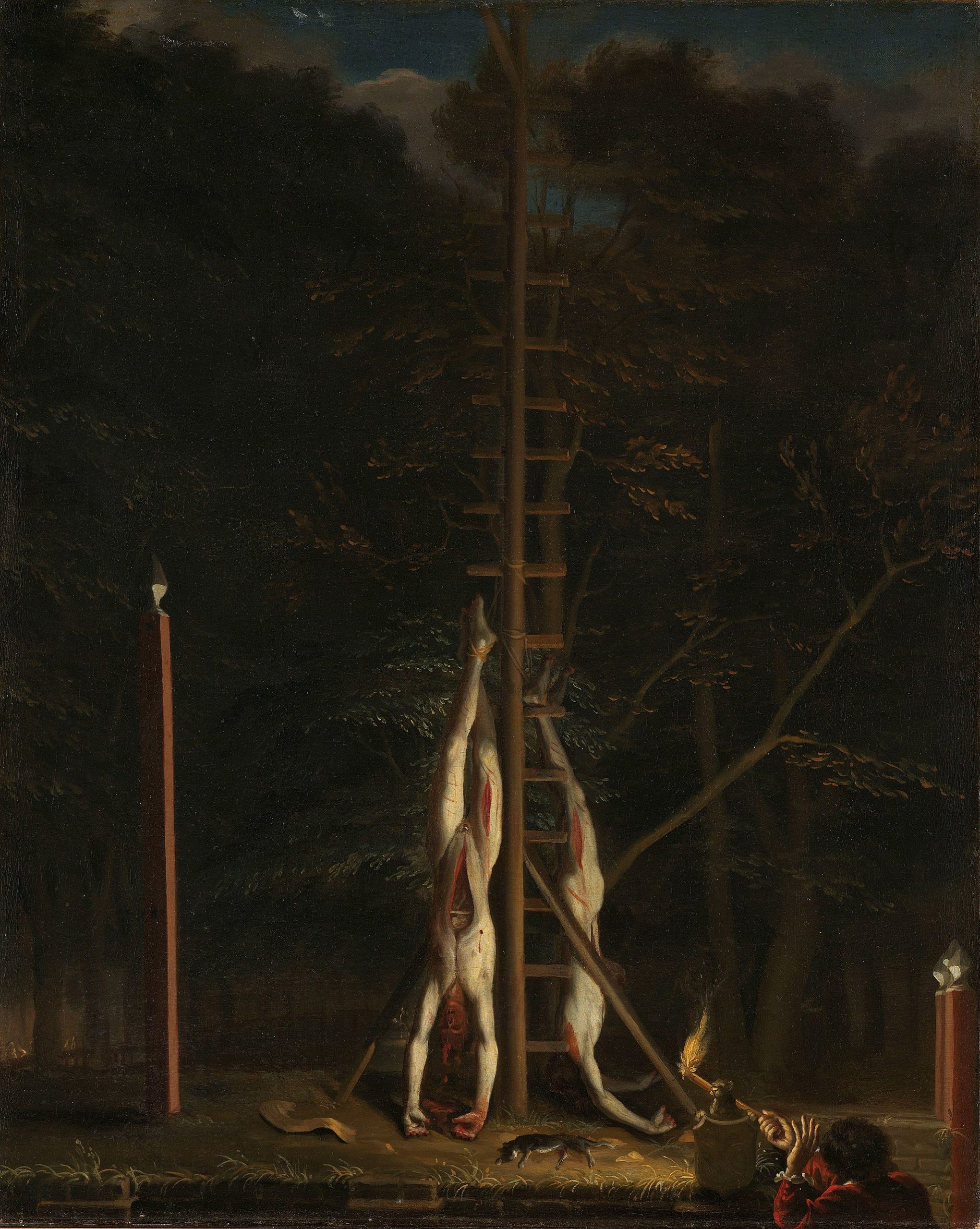

In the Killing Eve episode Desperate Times, Villanelle, our assassin for hire, stands bemused, quietly inspired in front of The Corpses of the De Witt Brothers. Two dead bodies hang, flayed and disembowelled as bodily flesh becomes meat, hung out to dry. The violence of the painting inspires Villanelle’s next kill, which like the painting is bloody, hyperbolic and grotesque. As she suspends her victim in a window in Amsterdam’s Red Light District, she replaces the bodies of sensual, dancing women for that of a dead man’s corpse. A simple economy of desire.

When I first began reading Virginie Despentes’ King Kong Theory, I thought a lot about Jan de Baen’s meaty, fleshy dead bodies. In this moment in Killing Eve, violence becomes entwined with sensuality—and the slippery boundaries between desire, pain, bodies, meat, skin and flesh.

Despentes’ collection of essays (originally published in 2006, and now translated by Frank Wynne for Fitzcarraldo Editions) is the literary version of a pickleback shot—vinegary, sharp, satisfying, short-lived. It is a proposition of gender outside of the misogynist binds of capitalism and toxic masculinity. The book emerges from a set of radical punk feminist tenets; it covers sensitive topics, from rape to sex work to pornography.

In one essay, Despentes writes: “I finally came to a conclusion: womanhood is whoredom. The art of arse-licking. You can dress it up as seduction, tart it up as glamour. It’s not exactly a sport that requires great skill. For the most part, it just means behaving like you’re inferior.” Her conclusions are always vitriolic, unexpected and divisive, her prose a cantering horse that suddenly bolts.

“Despentes’ collection of essays is the literary version of a pickleback shot—vinegary, sharp, satisfying, short-lived”

Despentes’ discussion of rape is frank, original and, like the rest of her essays, concerned with how to write these nascent violences into the world. Despentes argues that she never saw rape written or represented by women, that rape has no place in “symbolism”. So, in turn, she writes into rape, in order to get over her own.

In doing so, she references Camille Paglia, who was “validating the ability to get over it instead of meekly lying down amid a treasury of trauma”. This aversion to all that is submissive and meek is specific to the tonal cadence of King Kong Theory. As such, Despentes’ references to Paglia turned me off. When Emma Sulkowicz, then a student at Columbia university, New York, began their Mattress Performance in 2014 to protest that their alleged rapist was still allowed on campus, Paglia discussed Sulkowicz’s work in an interview with Salon, accusing them of parodying a specific kind of “grievance-orientated feminism,” and lamenting that Sulkowicz continued to “perpetually lug” their trauma around.

There isn’t always a direct correlation between an event, like rape, and how it manifests and affects the trajectory of one’s life—just because you appear to be “meekly lying down amid a treasury of trauma”, as Despentes suggests, doesn’t necessarily mean you aren’t also in the process of “getting over it”. Instead, she advocates for retaliation of some kind: “a wise up!”, get over it, learn how to defend yourself, don’t play by the rules, fuck you, hurry up and move on kind of feminism.

Jala Wahid, Dancing the Halparkeh, 2019. Courtesy the artist. Photo by Andy Keate

But implicitly, the “moving on” that Despentes advocates for doesn’t necessarily align with the affective fallout of her sexual assault, as it is described in the essays in this collection. At one point, she writes: “I constantly imagine that one day I will be able to be done with it. Eliminate the event, drain it, exhaust it. Impossible. It is a foundation stone. Of who I am as a writer, as a woman who is no longer quite a woman. It is what simultaneously disfigures me and makes me whole.” Ultimately, Despentes reveals the impossibility of skipping over her trauma.

You have to take Despentes with a pinch of salt: her writing is often ambiguous and, in places, she is purposefully difficult, misleading and incongruous. This is also the book’s strength. She is restless, keen to move forward, and in doing so her prose is scatty, brilliant and unflinching. Throughout, she teeters on a tightrope that explores the variegations of women’s physical vulnerability in its many forms. In her eyes, women too conspire in making themselves receptacles for the desires of men, bartering away their power in the process.

While Despentes argues that she writes “from the realms of the ugly, for the ugly, the old, the bull dykes, the frigid, the unfucked, the unfuckable, the hysterics, the freaks, all those excluded from the great meat market of female flesh,” the collection also seems to reveal the ways women collude and participate willing and unwillingly in the commerce of female flesh, whether we like it or not. To be excluded from the meat market, it would seem, is both impossible, and something that Despentes treats with ambivalence and fascination.

“She seems to reveal the ways women collude and participate willing and unwillingly in the commerce of female flesh”

The early sculptures of Jala Wahid also play upon the sexual politics of meat and animal flesh. Works likeCaramel Highlights (2015) appear like fleshy pink quartz entrails, or distended swollen organs. In Hard Blush (2014), Wahid’s gelatinous, bulbous tongue materialises the human form as apportioned, distended, split, torn, never whole. Bodies compromised—ruined—by violence, love, intimacy, civil unrest and pleasure. Images like Mallow (2015) pool and drip, sticky, visceral folds and pendulous orbs, served on platters like open, bruising, gutted papaya.

Like Despentes’ writing, I find Wahid’s work hard to look at sometimes; her Instagram serves as a platform in and of itself, and I often find myself squinting in discomfort and delight at the works (and works-in-progress) displayed there. They are reminders of the cruelty and pleasure of being a body. The experience of reading King Kong Theory is similar, and sometimes it’s hard to carry on; Despentes’ trades in bad politics, and her thoughts on gender, sexuality, feminism, aesthetics, are fleshy, ugly and coarse.

In The Sexual Politics of Meat (1990), Carol J. Adams aligns meatiness with manliness—strength, masculinity, dominance, whereas “women, second-class citizens, are more likely to eat what are considered to be second-class foods in patriarchal culture: vegetables, fruits, and grains, rather than meat.” It is interesting then, that in King Kong Theory, Despentes seems to advocate for reclaiming this meatiness, female “manliness,” by a recuperation of our ugly, subjugated, unfuckable flesh.

I have always felt squishy and uncomfortable in my body, a pulsing mesh of organs, hot, sweaty, clumsy. I have a skin condition where my skin is often itchy, and I am always conscious of how I hold myself. To be meat is to be undesirable, monstrous, marginalised. Despentes also hints at something even more complex: where do women find agency—strength, power, satisfaction, pleasure—in wanting to be reduced to meat? And how do we ensure that such a desire doesn’t belittle us, or make us vulnerable to the inexorable violences of the capitalist and misogynist systems in which we are inevitably enmeshed?

Come As Softly is a book column by Bryony White on intimacy, desire and sex.

Virginie Despentes, King Kong Theory

Translated by Frank Wynne

Published by Fitzcarraldo Editions August 2020

VISIT WEBSITE