The Recent grapples with one of the most urgent and pivotal matters of our era—the climate crisis. Bringing together video, installation, textiles and a daily memorial ceremony to mark wildfires taking place across the world today, the show calls for a radical shift in perception and priorities. Curating past exhibitions on the Anthropocene and nuclear waste burial, Talbot Rice Gallery Director Tessa Giblin recognises the transformative power that artists hold in reshaping perspectives on critical issues. “It does seem to me to be the way in which we as a cultural community and democracies can develop to be able to make the decisions that we need for the future,” she tells me. In ‘The Recent’, artists Eglė Budvytytė, Helen Cammock, Dorothy Cross, Regina de Miguel, Mikala Dwyer, Nicholas Mangan, Angelica Mesiti, Otobong Nkanga, Katie Paterson, Micol Roubini and Simon Starling collectively assert a stance on the environmental crisis, advocating for collaborative efforts to halt the destruction of our planet.

The geologist Charles Lyell and his various texts and journals recently acquired by the University of Edinburgh Collections were the starting point for The Recent, Giblin explains. “There was a moment in which he started calling a period in which we could see human activity and the geology of the planet ‘The Recent’, and it just was absolutely stunning to me.” The destructive impact that mankind has made in our relatively brief time here is significant: “We are beginning to recognise the consequences of our actions on the planet over the past two decades. However, geologists such as him and many other geologists assert that awareness of these issues has existed for an extensive period. The evidence has long been available. This understanding predates the coining of the term “Anthropocene” by Paul Crutzen in 2000. Contemplating this extensive awareness prompts me to consider how long we’ve been cognisant of these issues. It becomes a thought-provoking exercise to curate an exhibition that empowers artists to stretch the human imagination, not only into the deep recesses of the past but also forward into the future. The objective is to encourage contemplation that sparks more profound and intense considerations regarding the impact we are poised to make on the future of every living entity on this planet.”

Entering the exhibition, Angelica Mesiti’s ‘The Rain That Fell in the Faint Light of the Young Sun’ (2022) series of clay prints are first on display. The clay has pockmarks resembling raindrops that date back millions of years, aiding scientists in decoding atmospheric conditions and revealing geological insights into Earth’s history. A sound mimicking rainfall crescendo throughout the space from Mesiti’s video, Future Perfect Continuous (2022), in which performers recreate a rainstorm soundscape, symbolising the enduring power of ideas through time, rooted in the reimagining of ancient rain prints. Here, the enduring potential of play is evident. Unlike materials such as concrete or stone, which erode and undergo changes, and languages that may become unreadable over time, play and art offer ways to communicate through time, providing a lasting avenue for the transmission of ideas across generations.

Drawing inspiration from geological writers and individuals contemplating the shift in our perspective towards the future, Giblin speaks about a notable influence in the philosopher William MacAskill’s book, “What We Owe the Future,” which emphasises the importance of making decisions that extend beyond the well-being of our immediate descendants to encompass all individuals from the present onward. This includes acknowledging the role of future generations in our contemporary democracies. It is their voices that should be considered in the decisions we make today. Acknowledgement and emphasis on the past and our active engagement with ancestors are equally explored in Helen Cammock’s text derived from her broader project in New Orleans. Printed on a sky blue background, a single poetic sentence encapsulates the essence of her work: “If you take everything you like just because you like it just because you want it, the ghosts will have no place to play and the children no place to rest.” Her in-depth exploration of the city, with a focus on the experiences of black artists and individuals amid racism and post-Hurricane Katrina challenges, connects to the past, recognising the living presence of ancestors incorporating indigenous concepts of ongoing ancestral influence. A sprawling tapestry by Otobong Nkanga intricately intertwines the processes of the natural world. In the depths of the sea, bed lie entombed bodies and histories, serving as a reflection on the unequal impact of progress, underscoring how societal advancements have failed to benefit all communities equally.

Upstairs, an installation plays ‘The Magic Mountain’ (2022) by Italian filmmaker Micol Roubini. The work explores Europe’s largest asbestos quarry in Balangero, Italy. The toxic legacy of asbestos left the area desolate, contrasting its ancient magical and fire-resistant properties. Roubini gains access to the community around the mine, interviewing descendants of the miners to uncover collective dreams. Despite the toxicity, the inhabitants view their surroundings as a beautiful landscape. Katie Paterson’s ‘Evergreen’ (2022) displays 351 extinct plants intricately embroidered with silk thread on linen. The delicate tapestry serves as a commemorative gesture to lost plant species, inviting viewers to reflect on biodiversity loss and the interconnectedness of the natural world.

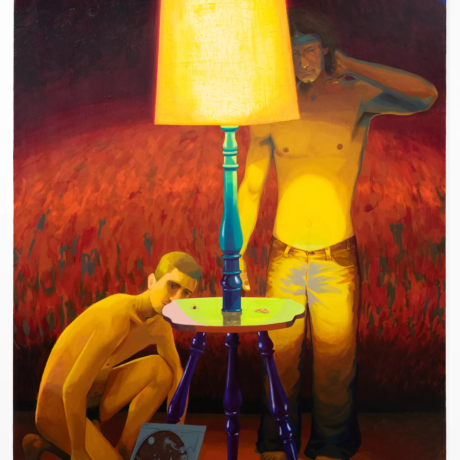

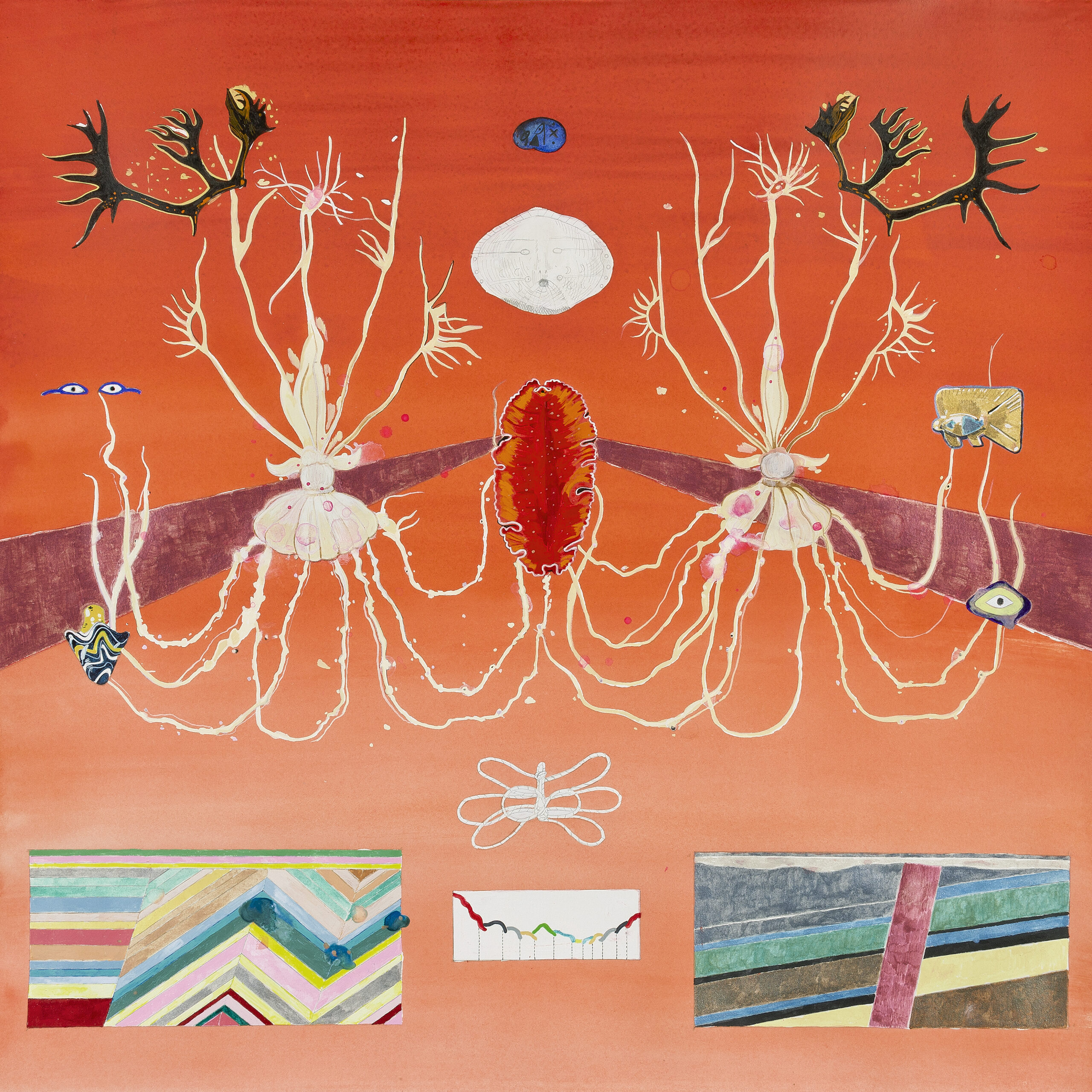

Continuing through the Georgian galleries, Regina de Miguel’s ‘Exvoto / Arrecife’ series is displayed for the first time. Watercolour, gouache, and pencil works on paper. The series resembles futuristic hieroglyphics, prompting fantastical decoding and raising questions about the connections between natural elements, spiritual artefacts, and the merging of science, art, and ritual. This collection explores how individuals across different times and worlds perceive their cosmic place, unravelling complex and interrelated ecological systems, leading to entangled, unresolvable questions.

Descending to the lower level, a projection by Nicolas Mangan presents a mass of particles drifting through a black void, intentionally keeping scale and context ambiguous—it is unclear whether the particles are enlarged dust flecks or a meteor shower. Unfolding at a deliberately slow pace, the work has a singular quality that mimics the unhurried movement of something drifting through the air at an extraordinarily slow pace. In ‘A World Undone’ (2012), Mangan extracts zircon crystals, the oldest mineral of our planet and residues from Earth’s early formation dating back around 4.4 billion years. Originating from Erawondoo Hill in Western Australia, the rock is crushed into microscopic fragments and filmed airborne against a black backdrop with a high-speed camera, capturing 2500 frames per second. With a fixed camera and slow movement, the imagery evokes both scientific and surreal aspects akin to outer space documentaries. The world, once in a state of constant formation, has shifted into a phase of gradual disintegration. This transformation marks a departure from the dynamic processes that shaped the Earth over millennia. This shift challenges conventional notions of stability and signals a new era where the forces of disintegration reshape the fabric of our planet. It prompts contemplation on the implications of this transition, questioning how we navigate a reality characterised by dissolution rather than construction.

Moving around, a tall screen plays Dorothy Cross Stalactite (2010). The film sees a young boy beneath an ancient half-million-year-old stalactite in the west of Ireland. He sings beneath the limestone, his high pitch echoing around the gallery space. Cross has explored communication through time by asking the boy to create sounds mimicking a bird, emphasising the challenge of conveying meaning across generations. Simon Starling’s billboard project ‘Autoxylopyrocycloboros’ (2006), known to many in Scotland, involved burning his own boat across Loch Long as a metaphor for our unproductive progress, sacrificing our means of survival. The final piece by Katie Paterson, titled ‘To Burn Forest Fire’ is a ceremonial artwork involving two sticks of incense representing the first and last forests. The ceremony is triggered by daily alerts of wildfires, memorialising the destruction occurring globally. With each passing day, a new sheet is added to the wall, visually chronicling the relentless impact of these wildfires on our planet. The piece not only captures the immediacy of environmental crises but also compels viewers to reckon with the ongoing devastation and the urgent need for collective action. In its solemnity, ‘To Burn Forest Fire’ resonates as a powerful testament to the fragility of our ecosystems and the imperative to address the environmental challenges confronting our world.

In a city defined by geological features, ‘The Recent’ stands as a collective call to action, tackling life’s complexities, the weight of our choices, and the imperative of human responsibility. Each artist recognises that the challenges of our era demand a unified response. The collaboration with Fruitmarket: Deep Time Festival, Project Paradise, and the University’s Centre for Research Collection’s exhibition ‘Time Traveller: Charles Lyell at Work’ amplifies this collective endeavour. As I navigate the exhibition, I can’t escape the urgency: when will the collective punishment on our planet cease, and what will be the catalyst for change? It’s a powerful challenge echoing through the landscape of ‘The Recent’.

Words by: Sofia Hallström