When you think of the material of choice for sculptors—whether bronze, clay or marble—polystyrene is unlikely to be the first to spring to mind. But a growing number of artists are turning their backs on more traditional tools to make use of a material better known for its use in takeaway boxes, packaging and insulation. Lightweight and brittle, polystyrene offers a welcome alternative to the heavier (in every sense of the word) properties and luxury associations of stone and metal. Cheap, accessible and increasingly ubiquitous, it is quite literally throwaway, allowing for a freer and more relaxed relationship with the sculpting process.

The growing prevalence of polystyrene is hardly surprising, given that we live in an age of hyper-convenience. Home delivery services will bring meals, laundry and almost any product you can think of direct to your door, as online shopping and one-click purchases continue to boom. Convenient they may be, but rarely addressed is the packaging that inevitably cocoons these shipments. Even as the conversation around recycling has gained traction in recent years—the UK has announced a ban on all single-use plastics from April 2020—postal packaging remains firmly resistant to the eco debate. Polystyrene is currently one of the most widely used plastics worldwide, with millions of tonnes produced each year.

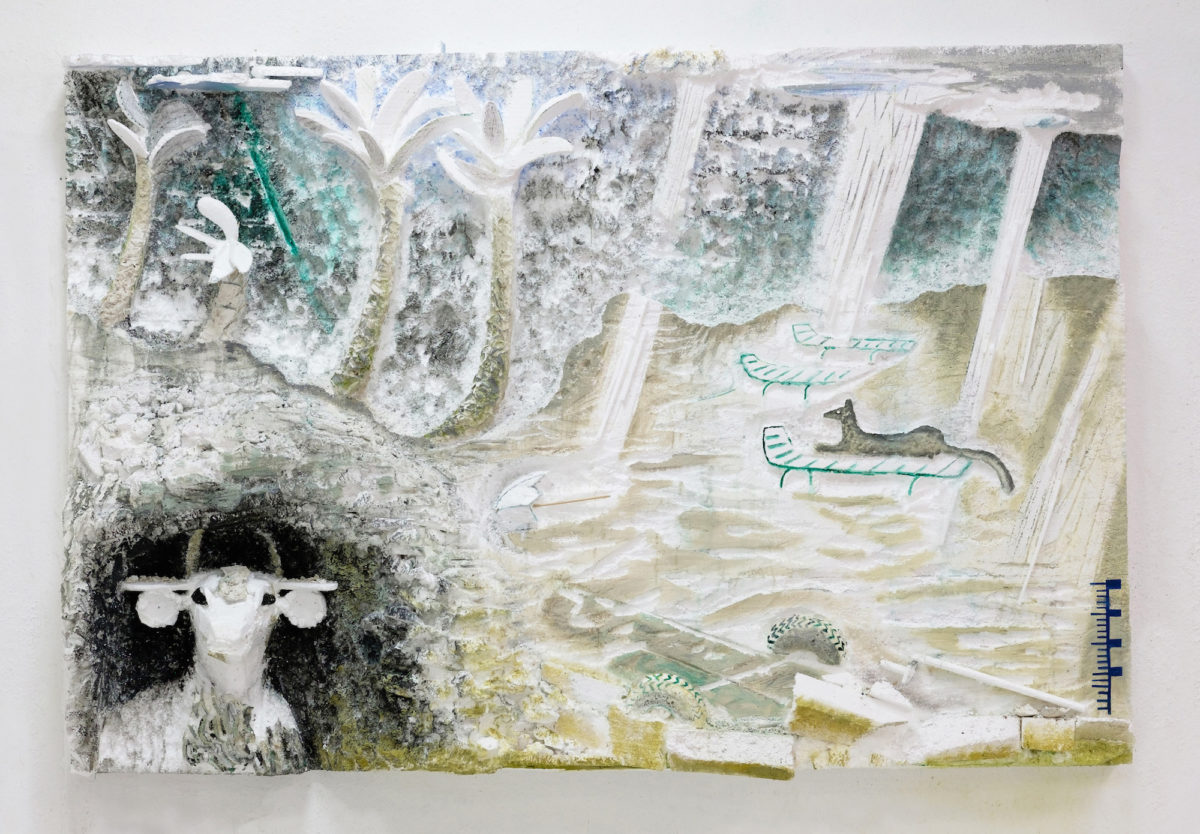

It raises the question of just what to do with all this plastic waste, often left littered around the house following a particularly enthusiastic unboxing. For German-Iraqi artist Lin May Saeed, polystyrene becomes the basis for her “un-monumental” carvings and sculptures, which take on a provisional, naive quality. Wall-mounted reliefs depict delicate scenes of men, women and animals at rest and at play, carved from thick polystyrene blocks. The familiar foamy texture of the material is emphasized in these miniature stage sets, with the stark white of the polystyrene left to show through the daubed paint. Saeed does not seek to elevate the material; rather, she celebrates it for just what it is—lumps, imperfections and all.

Life-sized sculptures of animals are carved from polystyrene by Saeed too, with the details of shaggy manes and matted fur adroitly rendered in stiff white plastic. In her solo exhibition, staged at Studio Voltaire in London last year, these wild creatures were placed on slender crates that recall those often used for the transportation of artworks. A nod to the many unseen processes that go on behind the scenes for the staging of any exhibition, the gesture also roots Saeed’s frequent use of polystyrene in the context of the global circulation of postage and packaging. Her work draws a parallel between the rapid cycle of commerce and trade in modern-day life, and the longer life cycle of ancient mythologies and the ebb and flow of migration throughout history.

“Polystyrene is currently one of the most widely used plastics worldwide, with millions of tonnes produced each year”

- Linneaus in Tenebris, 2017. Photo by Alban Gilbert

Guatemala-born Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa also explores folklore, mythology and displacement, in a varied practice that spans drawing, performance, sculpture, and video. Polystyrene is a material that he returns to again and again. Lightweight and cheap, it makes the ideal choice for performances in which it is worn or gradually destroyed by dancers. In Linnæus in Tenebris, a site-specific installation and performance staged at CAPC in Bordeaux, the scientific botanical expeditions taken in the eighteenth century in the wake of western colonization are explored. Violent hybrids—such as an arm protruding from a bunch of bananas—are carved from polystyrene, questioning the cultural hierarchies of the time and shedding light on the exploitation of the native workers.

There is an absurdist thread that runs throughout Ramírez-Figueroa’s work, bringing together everything from conspiracy theories to magic and mischief. Faux-relics are rendered in painted polystyrene, poking fun at the elevation of certain stories and materials over time—and asking questions about how and why history is shaped. Perfect plants, fruit and flowers are carved out too, ripe with the irony of the polluting effect of polystyrene on the environment, in an allusion to the historic impact of colonialism on nature previously left untouched.

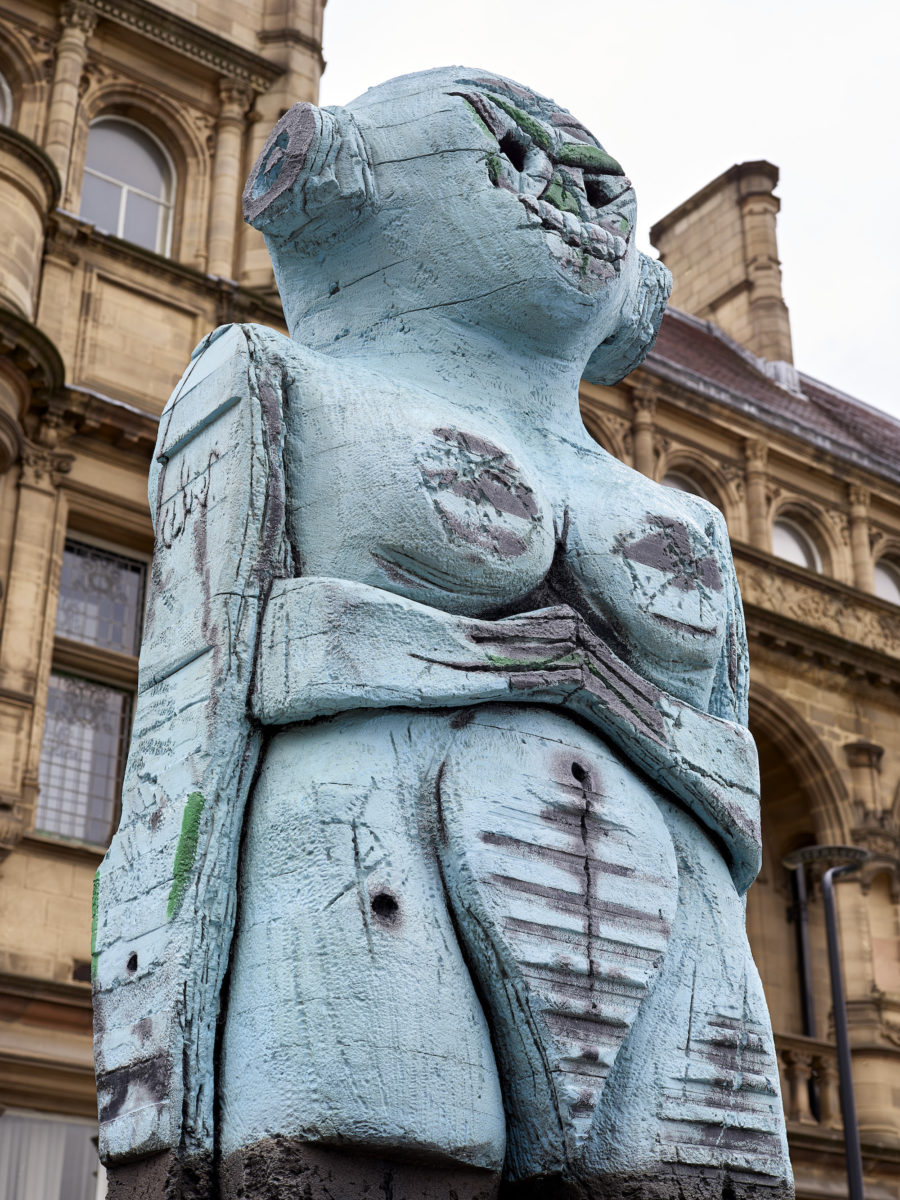

- Huma Bhabha, Receiver, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94 New York. Photo by Prudence Cuming

Meanwhile, the imposing presence of Huma Bhabha’s totemic figures belies their humble make-up, with the American-Pakistani artist frequently incorporating such materials as styrofoam, construction scraps and wire mesh. They make reference to everything from African masks to science fiction, recycling found objects and processes more typically associated with “craft” pursuits—such as papier-mâché. Viewed close-up, their scrappy, hand-made quality can be clearly seen; it is a far-cry from the smooth, polished finishes of more traditional sculptures. “I like the fact you see the sculptures here as original,” she explained in 2018. “While you understand the historical and contemporary influences that guide me, I’m pleased you can see this is my hand.”

“Their scrappy, hand-made quality can be clearly seen; it is a far-cry from the smooth, polished finishes of more traditional sculptures”

Of course, not all artists who incorporate polystyrene into their work choose to embrace its unpretentious qualities. Cheap and disposable it might be, but Nicolas Deshayes finds beauty in the precision of this man-made material. In Soho Fats (2012), he carves undulating waves into large panels of polystyrene, before mounting them on floor-to-ceiling handrails. With their bold simplicity, they echo the quiet beauty of Donald Judd’s own monoliths. Deshayes explores the divide between the messiness of everyday life and the cold sterility of synthetic packing materials, designed to neatly contain and transport the goods and ephemera that we choose to surround ourselves with.

The boxes that we pack and unpack over the course of our lives are conjured by Eva Rothschild in her current installation at the Irish Pavilion, presented as part of the fifty-eighth Venice Biennale. Great outsize blocks, sprayed in pastel colours, are stacked in the post-industrial setting at the Venetian Arsenale. Together, they nod to the historic architecture of the building—a former shipyard where cargo would have been loaded and unloaded on a near-daily basis. Although not made from polystyrene, the distinctive texture and colour of Rothschild’s sculptures are suggestive of it—a contemporary nod to the ever-growing mountain of stuff that populates our reality. Titled The Shrinking Universe, it points to the finite nature of our ecosystem and environment; just how much can we accumulate, destroy and discard before there is nothing left?

As the conversation continues to build around the endangered future of our planet, it is fitting that these artists are moving beyond the traditional preserves of sculpture. The art world is an industry that will often pay lip-service to environmental concerns, but it is rarer to see artists or galleries directly addressing the waste and energy expended in the constant creation, shipping and packing of artworks for exhibition. By making use of this most ubiquitous of packaging materials, they highlight an overlooked issue in how and why we consume, in both the cultural realm and beyond.