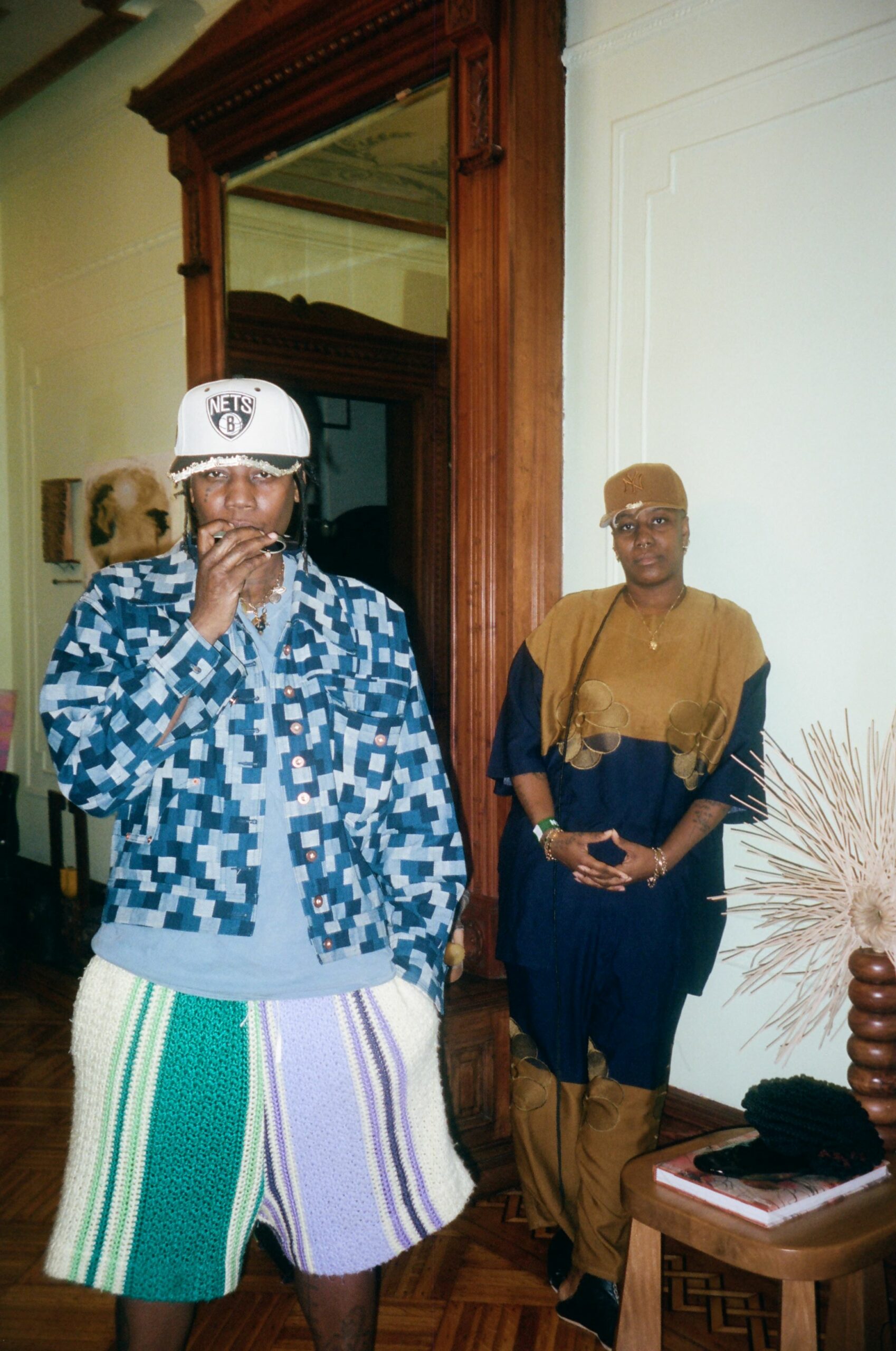

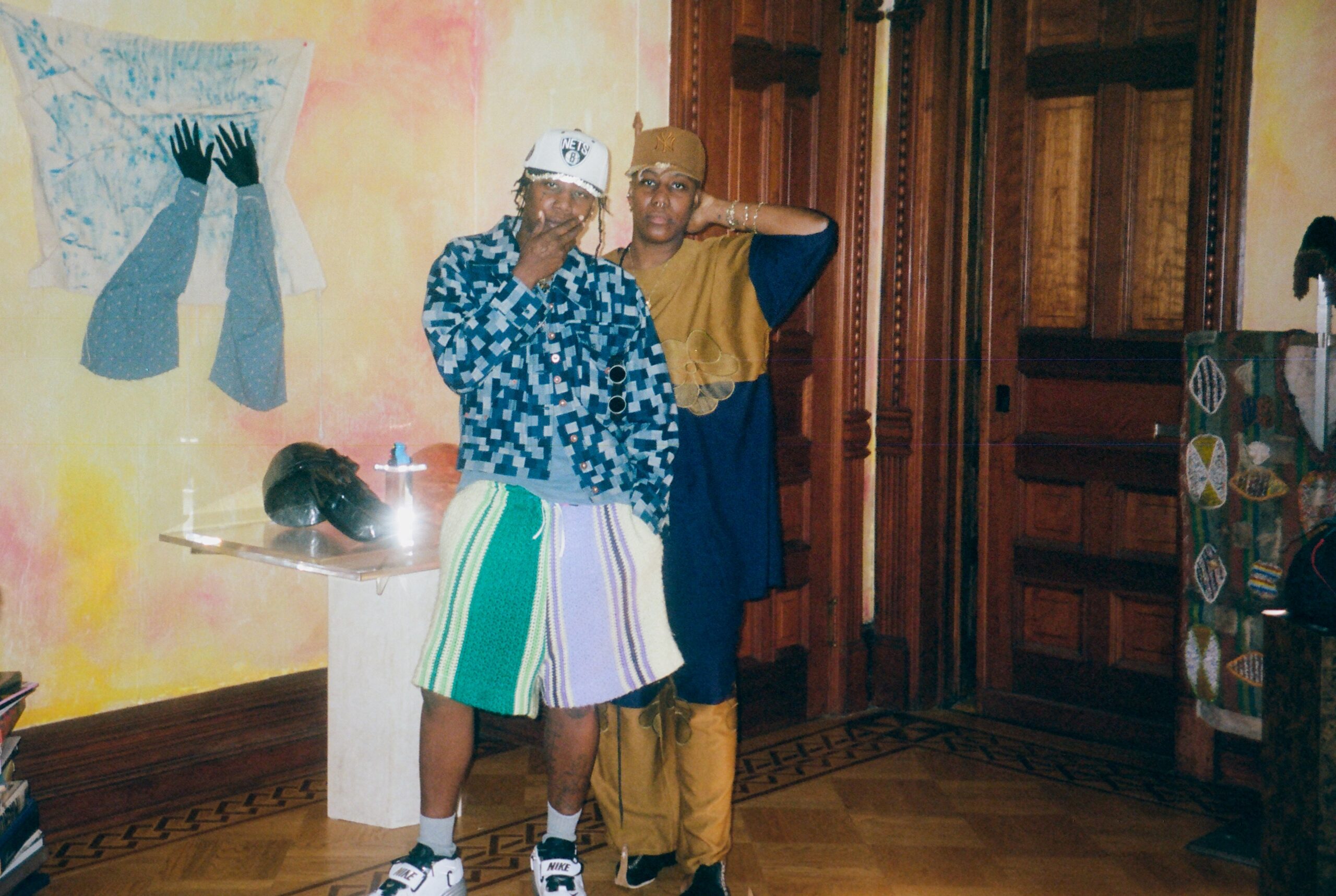

For their debut solo show at Salon 94 Design, identical twins and creative collaborators Soull and Dynasty Ogun blur the line between art and design.

“The beauty of entering the art world is that we are starting from a new place,” says designer and artist Soull Ogun. “We can become limitless.” Soull and her identical twin sister and creative partner, Dynasty Ogun, recently celebrated the opening of their inaugural exhibition at Salon 94 Design in New York.

K.O.D.E. (Keys Open Doors Everywhere), which runs until December 22, offers a thoughtful, kaleidoscopic window into the duo’s universe. Ideas from art and design cross-pollinate with exciting results.

Before the Soull and Dynasty found their footing in the art world, they established themselves as rising stars in the fashion scene. In 2017, they founded their design incubator, L’ENCHANTEUR, to merge their own labels. As L’ENCHANTEUR, they have designed jewellery collections for 3.1 Phillip Lim, created large custom pieces for Beyoncé’s film Black is King (2020), and outfitted celebrities including Erykah Badu, Lenny Kravitz, Ms. Lauryn Hill, Mary J. Blige, Bad Bunny, and Meg The Stallion.

For their debut solo show (born from an introduction by their friend, the celebrated visual artist Mickalene Thomas), the two embraced imperfection. To prepare for the exhibition, the twins tapped into a vulnerability that both expanded and doubled down on their oeuvre: new materials and forms gave shape to long-standing ideas. They veered towards conceptual choices not always afforded in the utilitarian, production-orientated world of fashion.

K.O.D.E. marks a new era for the sisters. A colourful mix of wearable art and sculptures — jewellery, tapestries, amulets, candelabras, textiles, and objects — reflect their dual visions in harmony; all works are available to purchase, creating a fluid and ever-changing display that mirrors the twins’ philosophy.

To put it simply, Soull’s background is in metal, and Dynasty’s is in textile. However, a deeper look reveals respective sprawling practices where the medium is a conduit for ideas around spirituality and mythology, self-discovery and personal history, numerology and science.

At Salon 94 Design, a layered storyline ebbs and flows across the space. Textured deep blue walls enter dialogue with Dynasty’s varied textiles, which mirror the scars that run up the artist’s hands (she endured severe burns when she was one-year-old).

A large table displays a treasure chest of accessories and objects made from gold and gemstones like lapis lazuli, diamond, opal, jasper, malachite, and obsidian. A golden headdress Name Spell Helm Wig (2023) features nameplates Soull made for clients in the past, fused together in a tender incantation. There are brilliant rings that recall Yoruba busts and a sculpture, THHT THHT, ELTHIRE (2020), which looks like one of Alexander Calder’s kinetic mobiles cast in precious stones.

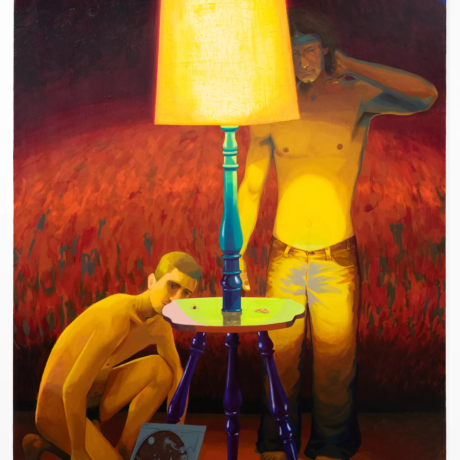

The gallery’s second and third stories hold concurrent exhibitions by Karon Davis and Myrtle Williams. “Myrtle Williams has been an artist her entire life, but this is her first show. Then you have Karon who is a practising artist and has been doing the thing, and then you have us who are essentially being introduced,” Soull says, noting that one of her “Name Spell” wigs can be found on a figure in Davis’s exhibition. “It was this beautiful, collective story,” she reflects; one that underscores the community ethos at the heart of their practice.

Born and raised in Flatbush, Brooklyn, Soull and Dynasty grew up inspired by their vibrant, multi-cultural environment. They first channelled their desire to know the world into their high school studies — Dynasty followed her father’s footsteps and went the engineering route. Soull studied art before switching to psychology in response to a didactic teaching style that reinforced her belief that being an artist was something that came from within, rather than something that could be learned.

Soull and Dynasty arrived at their respective crafts intuitively, as if they were fated. Their last name Ogun, which they abbreviated from Ogunmoyin, represents the Yoruba God of metal. Although they have developed individual practices, the two operate on a shared cosmic vibration. “People search for their twin flame, search for a soulmate their whole life,” says Soull. “There’s a saying that twins automatically share the same soul.”

The twins credit their deep bond as an entrypoint to self-awareness. They finish each other’s sentences, filling in words and building off ideas in synchronicity. Once you know yourself, it is easier to have empathy for others, they tell me. Growing up, their father spoke in proverbs. “Know thyself” was one of his most popular.

If you are at home within yourself, you will be at home anywhere, they explain. They dream of travelling around the globe with their art, they tell me, sharing an enlightened framework for seeing with as many people as possible.

“We came into this world specifically at this time to do this, to be this,” Dynasty says. “Maybe our bloodline was trying to bring forth that energy.” In Yoruba’s pantheon, twins are regarded as magical, represented by ibeji, a sacred orisha spirit.

Their parents both immigrated to America to pursue a better life for themselves, get an education, and find work. Their late Dominican mother was a talented seamstress from a lineage of designers and carnival costume-makers who taught the twins to tap into their personal style from an early age. Their Nigerian father comes from a community of metalsmiths (and, they learned later in life, was a practising metalsmith himself before moving to America). Now, their daughters are exploring the creative traditions they left behind.

“Watching my parents be so brilliant and talented and go for something that seemed safe and stable, and still quote unquote struggle — for me, it opened the vortex of reach for my dreams,” Soull says. If their parents were born today, maybe they would have been artists, too.

In other dimensions, Soull is a doctor and a therapist, and Dynasty is a classical musician and an electrical engineer. In the present, art gives them the opportunity to be everything all at once. “Sometimes when I’m sitting at the machine, I feel like I’m making music,” Dynasty says. “I may pull from the pianist that I wanted to be in first grade.”

The twins recognize themselves as part of a new generation of diasporic artists seeking to uncover, elevate, and rework spiritual and technical traditions of their motherlands. “I’ve been noticing so many different individuals learning crafts, creating with their own hands,” says Dynasty. She is excited about a future that honours the ideas and skills of artisans across the globe, a future, she says, that will hopefully open the doors for those artisans to sustain themselves financially.

They also note a changing of the tides as far as the importance of formal schooling. The duo are autodidacts, and honed their skills outside of institution walls, through experimenting in their art studios, meditating, work towards self-discovery, and learning from their community. “Dynasty and I are self-taught, and because of that we feel that education is a fluid thing,” Soull says. “It’s a breath of fresh air to value art without needing credentials.”

Soull and Dynasty’s energetically charged works are imbued with shared and personal histories. Their objects, both wearable and decorative, are made to be passed down to generations. “Everything that we surround ourselves with, we tend to make beautiful,” says Soull. “Then someone spots it. Gentrifiers act like the community wasn’t valuable before, but people want to come here because the culture is rich,” she says. “Indoctrination, assimilation, and colonialism swing like a pendulum.”

“Our company has been about identifying luxury in a scarred world, within a world where you would be tricked into thinking that value doesn’t exist,” Dynasty adds. “When people take from a community or take from a certain genre or idea of style, it’s like, oh, they took from it and brought it to a heightened sense of value, when it was already valuable. That’s the reason why they took it,” she emphasises.

“We want to tell our stories in a rich way, so our audience can feel empowered to make internal changes that can change their community, society, and then the world,” Soull says. Dynasty nods in agreement, gesturing her hands outward: “everything is beautiful in essence, even in imperfections, the way a branch can grow off a tree, the way a crack can grow in the concrete,” she says. “We’re from the concrete jungle — roses grow out of the ground all the time.”

Words by Meka Boyle