If I think back on my time in education, I can’t remember a deadline that I didn’t miss. I existed in a perpetual state of procrastination, veering between the two extremes of anxious avoidance and accelerated productivity in a state of crisis. These bad habits only worsened when I arrived at university, where I discovered that I could never predict the moment when the inclination to finally get down to work might choose to strike me. It got so bad that, for a period, I wasn’t able to even start a task until after the deadline had passed. For years I wondered if I was just lazy, but I have begun to consider the possibility that my approach to work has long been bound up with a larger, holistic sense of self. School represented only a small part of who I understood myself to be, and I was only able to fulfil its demands to the degree that I saw myself reflected within it.

For many in the creative industry, their work is intimately bound up with who they are. As my personal and professional life have become increasingly entwined, I have found it easier to motivate myself without the need for a panicked rush towards the finish-line. For artists, designers, writers, musicians and others, the impulse and ability to generate new ideas doesn’t take place within a vacuum. The boundary between leisure and labour is frequently blurred, whereby a casual conversation or offhand recommendation can find its way from a private exchange to a visible creative outcome

. It is a form of work that requires the radical and total absorption of the self, where personal taste and interests collide with the ordinary demands that come with earning a living. Where I previously had teachers to argue with and ultimately dismiss when I failed to deliver, to miss a deadline in the creative world is to reckon with no one but yourself.

“The endless scroll invites us to perform a version of who we are, and to offer an identity that feels relevant to the work that we do”

As a teenager in the mid-2000s, I came of age with the blossoming of social media. From LiveJournal to MySpace to Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, the overlapping of public and private has long been familiar to those who grew up with an internet connection. I had the ability to rapidly upload my youthful inspirations in Tumblr posts that could be re-shared thousands of times, while contemporary iterations of social media invite even more frequent updates of text, image and video. These digital platforms enable an accelerated performance of the self, breaking down the distinction not just between personal and professional, but between fiction and reality. The endless scroll invites us to perform a version of who we are, and to offer an identity that feels relevant to the work that we do. At their best, these networks offer opportunities for meaningful forms of connection; at their worst, they promote a relentless drive to compare ourselves against the online performances of others.

When almost anything in daily life can now be quantified, from online followers to step counts, it is easy to feel like you are falling behind. It was announced last week that Twitter is to introduce a paid subscription-based model, allowing “internet creators and influencers” to monetise their online popularity. “Exploring audience funding opportunities like Super Follows will allow creators and publishers to be directly supported by their audience and will incentivize them to continue creating content that their audience loves,” the company said, in a statement that raises again the difficult question of personal motivation. While these revenue streams might offer an additional incentive to some, the new model ultimately only reinforces the already-entangled relationship between work and life.

The stakes are inevitably high when so much of who you are is bound up in the work that you do, and in the labour of promoting that work online. What happens if you lose a job, or take a step back due to significant life changes such as maternity leave, illness or caring duties? Many have been forced to reckon with the impacts of falling ill with Covid-19 during the last year, with some suffering from the devastating and destabilising effects of long Covid. Amidst a culture of hyper-visibility, not to mention the extreme financial precarity of the arts, disappearing from the stage even temporarily can feel risky. To lose work (whether through choice or circumstance) is to lose a part of who you are. While I don’t tend to miss deadlines anymore out of choice, I sometimes question how I would feel if that decision was suddenly taken out of my hands.

“When almost anything in daily life can now be quantified, from online followers to step counts, it is easy to feel like you are falling behind”

Visibility remains an important form of currency within the art world and beyond. Last month, it was reported that Rolling Stone magazine was offering “thought leaders” the chance to write for its website for a fee of $2,000 to “shape the future of culture”. Those selected would “have the opportunity to publish original content to the Rolling Stone website”, allowing them to “position themselves as thought leaders and share their expertise”. It represents a shocking distortion of access to the industry, and takes the commodification of creative influence to the extreme. Like the unpaid internships that continue to plague the sector, the bizarre Rolling Stone scheme represents yet another exclusionary form of preference through privilege and wealth.

It is often said that to work in the creative world at all is a privilege. While the opportunity to involve a more holistic version of yourself in the work that you do is undoubtedly a source of joy for many, there remains the issue of burnout. If so much of your work and your leisure are bound up together in a single identity, how do you take refuge when you need a break? The production of creative work often requires an intense form of engagement that relies on self-belief and determination; at times when these emotional reserves are drained, it can trigger a crisis. I find myself caught up endlessly in the cycle, aware of the fragility of the balance between personal and professional and yet unable—or unwilling—to stop.

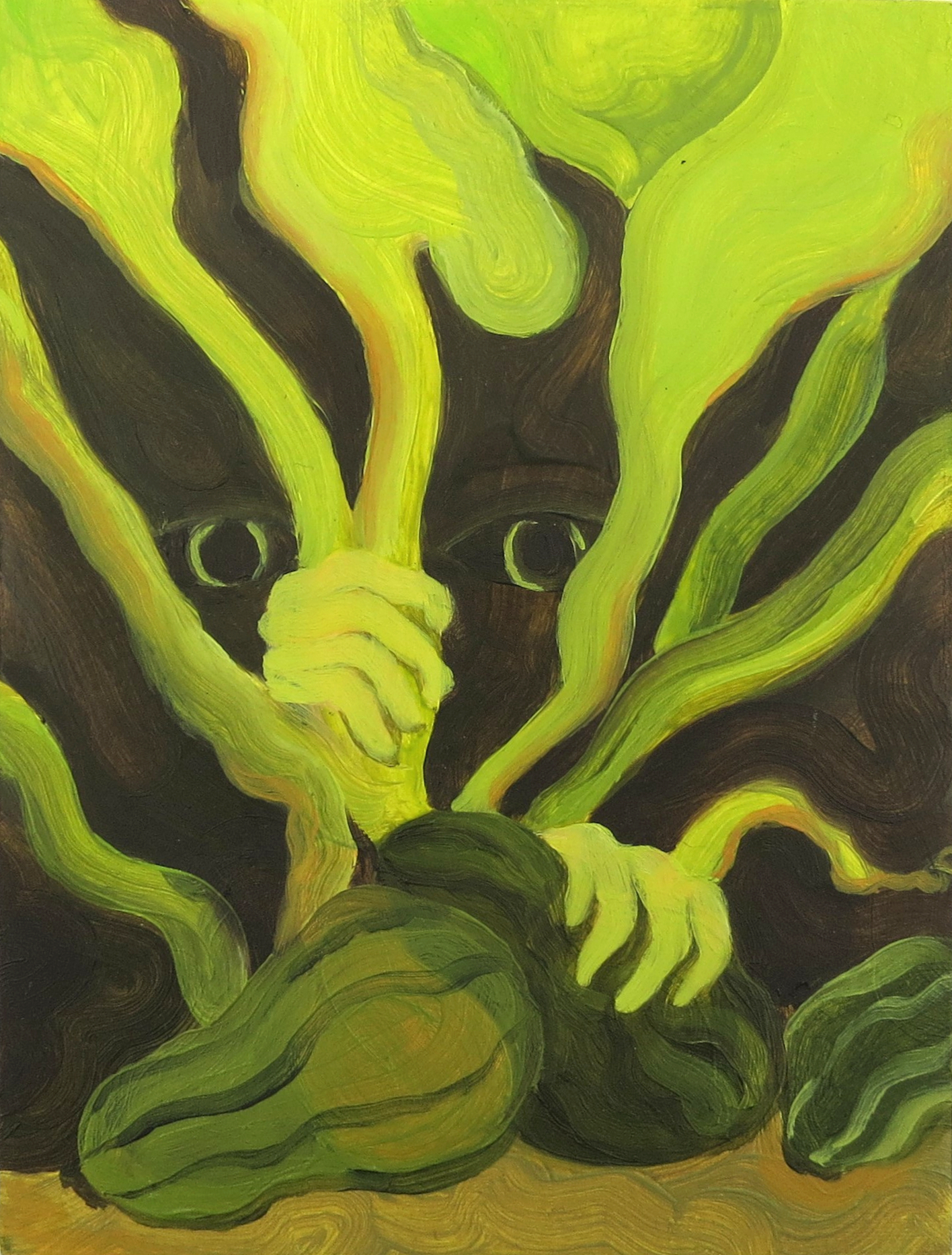

Are We There Yet is a fortnightly column by Louise Benson. Top image © Georg Wilson