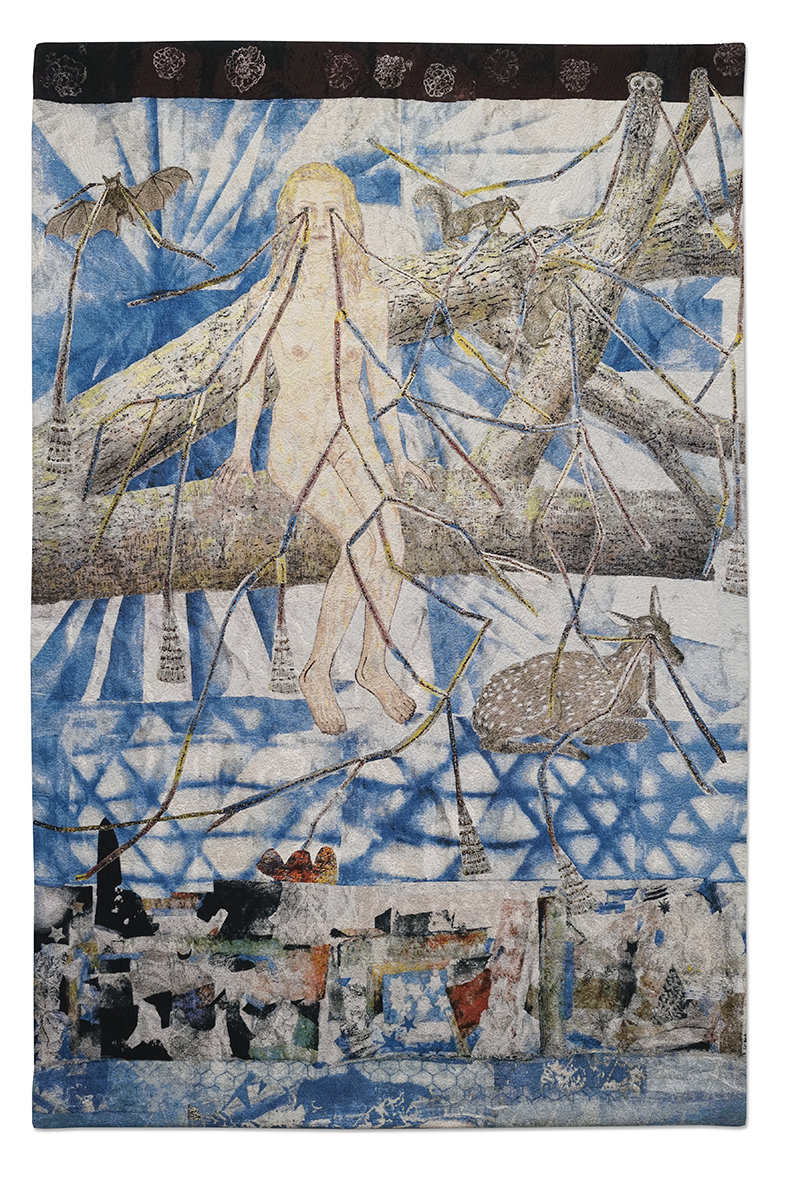

Kiki Smith, Earth, 2012

Kiki Smith has always been an artist driven by process, and more specifically by printmaking. Though her considerable oeuvre spans everything from sculpture to photography, she considers printing the jumping off point, and the inherent flatness that the process offers can be seen in the strange two-dimensionality that exists in works made from bronze or aluminium.

Printmaking also plays an intrinsic part in an ambitious new series of tapestries currently on show at Timothy Taylor. These enormous textiles—made in collaboration with Magnolia Editions—depict imagined scenes that reference nature, cosmology, twenties advertising and “hippy iconography”, as well as recalling the allegorical and narrative histories of traditional tapestry. Though the jacquard weaving process has a distinct cultural legacy, it has found new life in contemporary interpretations, because the binary production method is perfectly adapted to computer systems. This has made it possible to produce incredibly detailed works that would have been previously unfathomable.

“The life-sized wolves, deer and birds are every bit as fantastical as a stroll through a Grimms’ fairytale”

Smith’s incredibly rich and dense tapestries are a testament to that. Each piece was originally conceived as a mix of collaged drawing, painted paper and lithograph, in a process of reworking that Smith has always enjoyed. In the gallery, she points out various animals, objects and constellations that have been reconstituted from previous bodies of work and relishes the incredibly breadth of colour the jacquard has allowed her to achieve.

Kiki Smith, Congregation, 2014

These woven palettes not only build up incredible colour density, but wonderful textures, with the odd bit of alluring shimmer achieved with metallic thread. Interacting with these pieces offers multiple experiences, because you encounter them first from afar as flat, cohesive images, before drawing closer and investigating diverse surfaces, line thicknesses and individual vignettes within the wider whole. Though Smith attests that there is no real narrative, you search for stories in every stitch, and the life-sized wolves, deer and birds are every bit as fantastical as a stroll through a Grimms’ fairytale.

There is something utterly luxurious about viewing these works, and that must be in part due to the way we have been socialized to marvel at the tapestry form, as an object of propaganda or coded history that demands attention and reverence. Smith’s contemporary take does not chronicle epic battles or family lineage, but instead offers unfettered escapism that is refreshing in its universality. These strange lands are ultimately the domain of her own imaginings, but they represent something everyone can hold on to.