I used to cringe on the rare occasions that we would eat out with my Chinese mother and her old friends from Hong Kong, dreading the moment when the bill would come. As the waiter approached, the ordinarily composed group of women would begin to push and shove one another, shrieking as each sought to grab the prize amidst the scrum. It was worse than bridesmaids and a bouquet at a wedding, and twice as loud. When it was all over, I would ask my usually frugal mother why on earth she was fighting to pay for everyone. “Just let one of them cover the bill, it’s what they want,” I would grumble. “You’ll understand when you’re older,” she’d always reply.

Of course, I can see now that the heated exchange at these long lunches was rooted in the pleasure of giving. I have been thinking again of these conversations with my mother as the current lockdown pushes many to reconsider their attitude to generosity, and to giving and receiving. For those who find themselves furloughed or without work, it may seem like the ideal moment to embark on those creative projects that they never found the time for before. But, in the age of the internet, it is all too easy for casual hobbies to quickly be weighed up in terms of their immediate value.

“Artistic or creative pursuits, endeavors that are typically pursued for the intrinsic joy of sharing one’s gifts, are also frequently commoditized and placed on the market. Are they part of the gift economy or the transaction economy?” This is the dilemma explored by Ted Gioia in an article published last month in Image Journal, titled “Gratuity: Who Gets Paid When Art Is Free”. Is it possible to give away a song, artwork or film online when the exchange is never truly equal? Somewhere in the chain, someone is profiting.

“Welcome to the inescapable foundation of artistic alienation in the digital age. Even artists without financial worries—maybe a working spouse or trust fund pays the bills—understand this conflict,” Gioia writes. “If they give their talent away, they feel shortchanged and exploited, but if they attach a price tag to every creative act, they betray the essence of their gift.” In short, the original pleasure of giving has been stripped away.

“Hobbies are left to languish, unless they too can be incorporated into the relentless drive towards a version of success“

I have heard from friends who feel under pressure to be productive and to maximise their opportunity for self-improvement during this period. While even the most innocuous of activities, from gaming to cooking, can now be monetized in IGTV clips and sponsored livestreams, this pressure to perform goes deeper than the immediacy of cash returns.

Jenny Odell reflects presciently on our present moment in How to Do Nothing, her 2019 book that advocates resistance against the powerful forces of digital capitalism. She writes: “In a situation where every waking moment has become the time in which we make our living, and when we submit even our leisure for numerical evaluation via likes on Instagram and Facebook, constantly checking on its performance like one checks a stock, monitoring the ongoing development of our personal brand, time becomes an economic resource that we can no longer justify spending on ‘nothing’.”

It is a dilemma that will be familiar to almost anyone who has freelanced in the creative industry in recent years, as well as those who are overstretched in underpaid jobs in the sector. When the path to progression is muddy and indistinct, it feels like every hour spent working towards that bigger goal might finally lead to one breakthrough or another. It is a path that prompts many to accept work for free, or to invest valuable time into their social media presence. Meanwhile hobbies are left to languish, unless they too can be incorporated into the relentless drive towards a version of success. To paraphrase, “If a tree falls in a forest and no one puts it on Instagram, did it really happen?”

We must now reckon with how we spend our time and where we direct our attention. As galleries open “online viewing rooms” and release daily digests of what to watch, read and listen, it can feel surprisingly easy to remain as distracted and overloaded with information as we ever were. There is more art available for free than ever, but is it the best thing for us during this time?

“There is a pressure to remain constantly busy, even when doing nothing has never been easier“

“The gallery system has snookered itself by becoming, broadly, structurally unable to handle a break in operations; hence the frantic pivot to online art fairs, etc. Magazines, too, need a steady crop of fresh faces to suggest or simulate dynamism,” Martin Herbert argued last week in Art Review, in a piece titled “Why taking a break is a good thing for people who care about art”. There is a pressure to remain constantly busy, even when doing nothing has seemingly never been easier.

“It remains to be seen whether, bumpy ride though it will undoubtedly be and not without undeserved casualties, the artworld reverts to a more manageable, less monolithic scale that makes it easier to honour art with our attention, perhaps our newfound attention, to it,” Herbert writes. It is an attitude that could well be extended beyond the work that we consume to that which we produce.

A pandemic is the time to rethink generosity in many forms. Attuned as we are to seek external value in everything that we do, it is difficult to feel useful or productive during a global crisis. We don’t just need a break from the usual order of things, we need a radical untangling of what we give away and what we keep; what we sell and what we protect. We need to remember to be generous not only to others, but to ourselves.

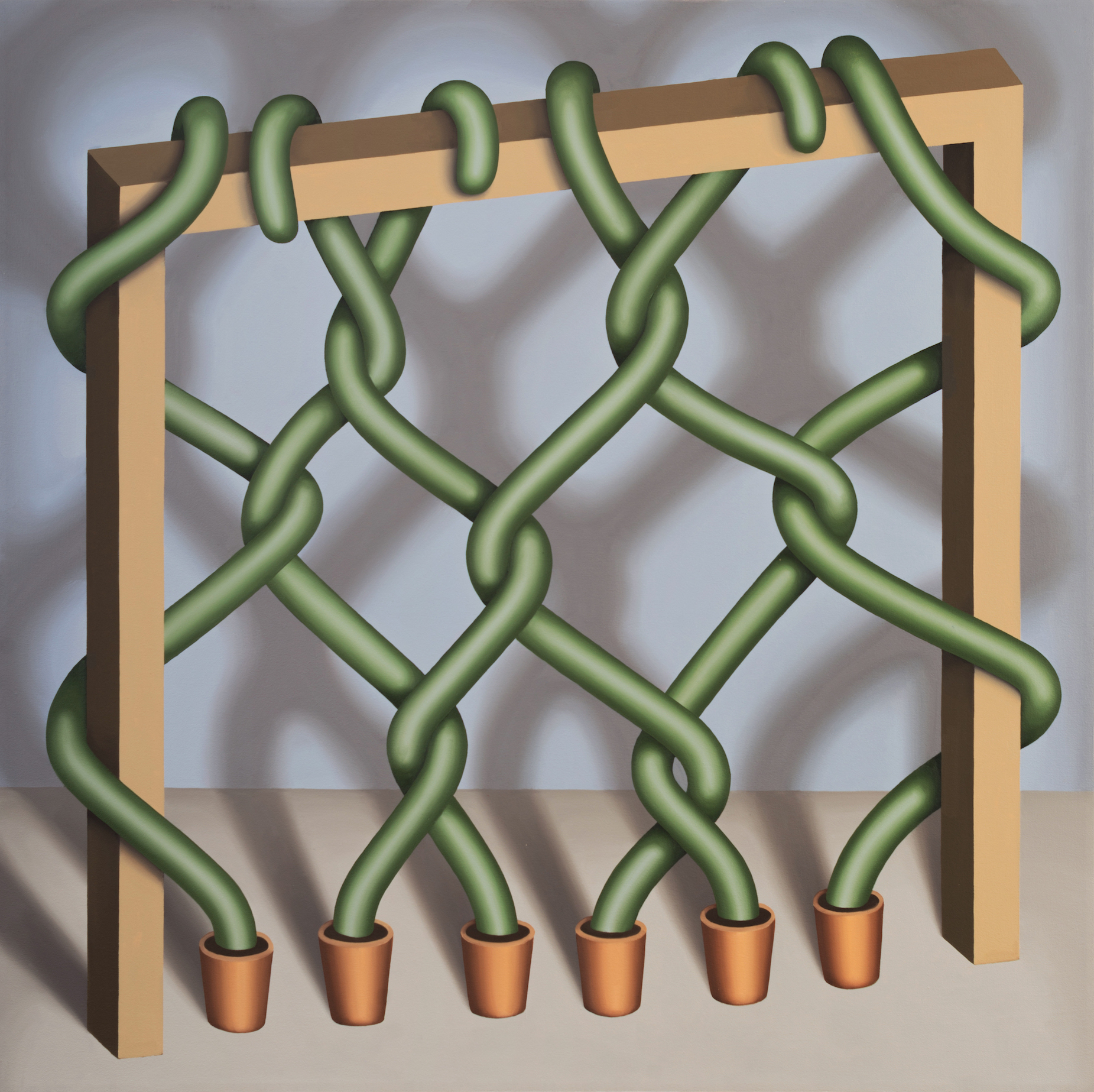

Are We There Yet is a fortnightly column by Louise Benson. Top image © Emily Ludwig Shaffer