Writer Katie Tobin reviews Hayward Gallery Touring’s current exhibition ‘Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood’, curated by Hettie Judah and contextualises it within a history of feminism and the complicated relationship between the female-artist and motherhood.

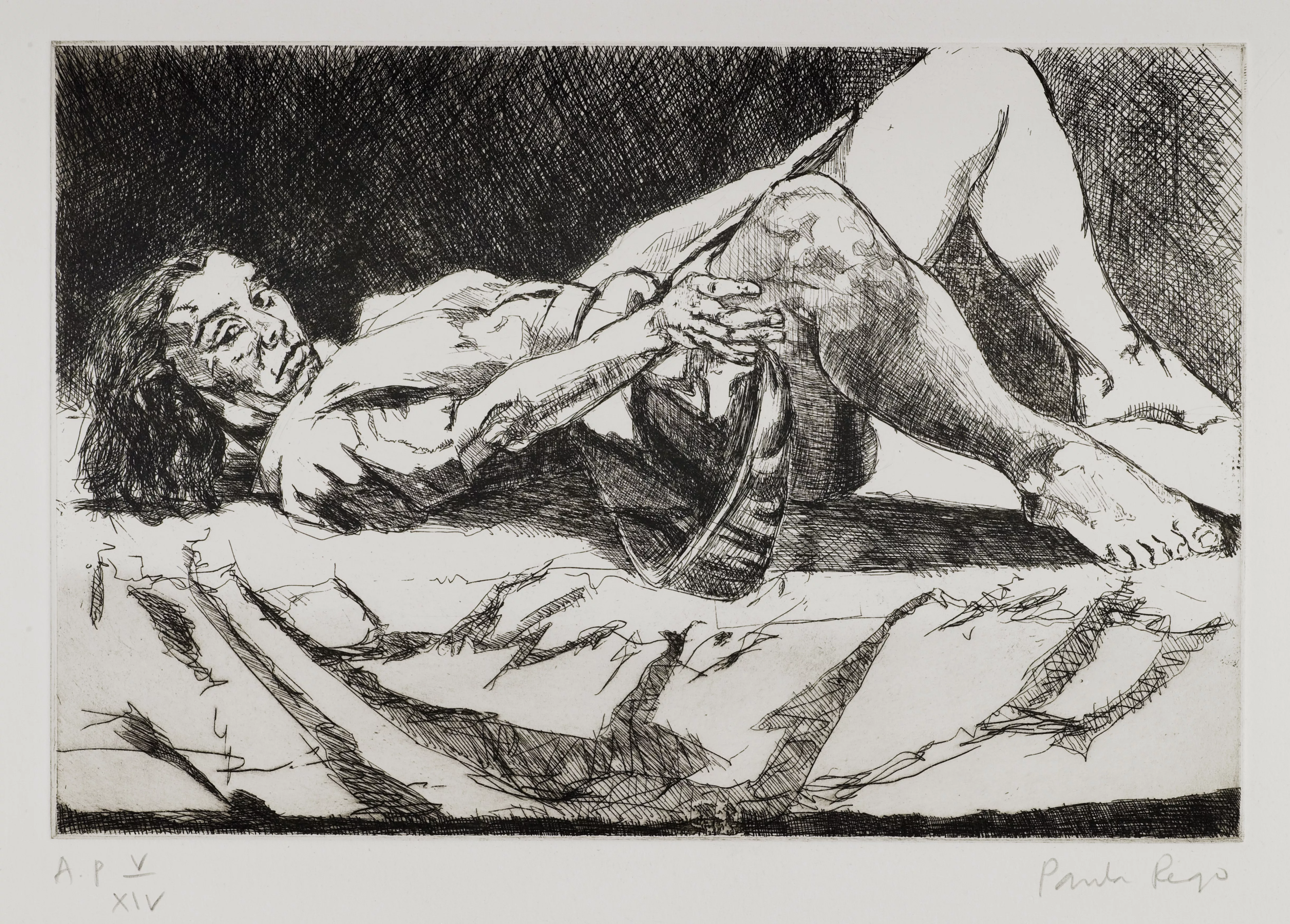

When tracing the long lineage of mothers in art, a few works spring to mind. Da Vinci’s Madonna Litta (1490) for one; Rembrandt’s The Artist’s Mother (1631) and Van Gogh’s Madame Roulin and Her Baby (1888), too. Many of these early depictions are reminiscent of the Virgin Mary herself: benevolent, ethereal, immaculate, patient, and pure. A fallacy as old as time itself, the idealised mother figure looms large in art and culture throughout history. But as art historian Katy Hessel notes, these portrayals are ‘symbolic rather than actualised’ and, crucially, a product of the male mind. It wasn’t until the twentieth century that artists like Alice Neel and Louise Bourgeois helped to deconstruct this mythos by bringing complexity and nuance to the subject. While Neel’s portraits desecrated the good mother archetype by capturing the potential brutality and pain of parenting, Bourgeois’ The Good Mother (2003) sees long white threads extend from the breasts of a small pink body, trapping her in an endless cycle of creation and reproduction.

This begins a useful way to think about Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood, curated by Hettie Judah with Hayward Gallery Touring, now showing at the Midlands Art Centre. Framing motherhood as a creative endeavour—albeit one that may be tempered by ‘ambivalence, exhaustion or grief’ at times—Judah’s curation strikes a careful balance between advocating for the rights of mothers, including the right not to be one. As Julie Phillips notes in her 2022 book, The Baby on the Fire Escape: Creativity, Motherhood, and the Mind-Baby Problem, ‘Reproductive rights, including access to abortion, contraception, fertility treatment and healthcare—are a necessary part of creative mothering.’ Titled after an incident whereby Neel left her daughter unattended while painting, Phillips’ book is one of a few recent inquiries into the (in)compatibility of artistry and motherhood. Judah’s own How Not to Exclude Artist Mothers (and Other Parents) (2022) is another. ‘I’m wanting to make the case for the artist mother as a serious cultural figure,’ she tells me. ‘Although there have been exhibitions about motherhood in the past, what’s really particular about this one is that it addresses motherhood both as a state and as a subject—it’s looking at what it means to make art as a mother and see that it’s possible.’

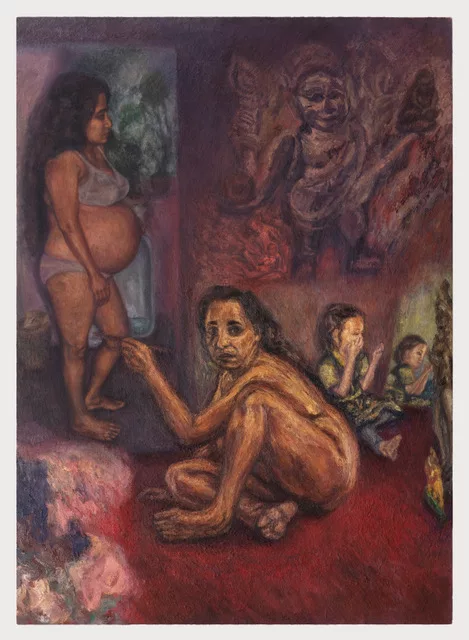

So vast is the subject matter of Acts of Creation that it’s hard to take it all in on first viewing. ‘As is probably evident looking around, I’m talking about motherhood in an extremely expanded sense,’ Judah says. This much is true. The first section of the show comprises works that focus on creation itself—conception, pregnancy, birthing and nursing. Ghislaine Howard renders her stretchmarks in charcoal, Catherine Elwes films her own lactating breast. To my mind, one of the most striking pieces is Lea Cetera’s sculpture You Can’t Have It All (2022). Resembling a womb and fallopian tubes, it’s a timely—quite literally—reminder of the fertility clock women are warned about from a young age. Elsewhere, Caroline Walker’s painting of bottles and pumps makes for an intriguing, if unconventional, still life.

Moving towards Judah’s temple—a room painted with royal blue and a band of gold—I find a room filled with playful subversions of the Madonna and child. Leni Dothan’s Sleeping Madonna (2011) film shows the artist stylised as stylised like a Renaissance painting, breastfeeding her child. Ishbel Myerscough’s All (2016) is a testament to the artist’s wider study of coming-of-age in portraiture, carefully hung next to friend and collaborator Chantal Joffe’s portrait of herself and her daughter.

This room, rich with lurid colour, lies in stark contrast to the section next door devoted to loss. Standout pieces include Nancy Willis’ Self Portrait with Lost Baby (1988) and sculpture Her Name is ‘Rosie’ (1990), Elina Brotherus’ photographic series documenting her journey through IVF, and Tracey Emin’s Something’s Wrong (2002), a depiction of her botched abortion. For Judah, accounting for these experiences was of paramount importance. ‘This show isn’t just focused on artists who do have children; it’s also concerned with the children we decide not to have,’ she tells me, ‘the children we wanted but were unable to have. I’m not the first person to say this but anybody who has had to think about whether they’re pregnant or they might become pregnant in the future is, in some way, involved in this discourse around motherhood. It’s for all of us.’

Indeed, the loss section feels especially uncanny to bear witness to. Between the rollback of abortion rights in the US, the increased surveillance of them in the UK and the horrifying lack of reproductive healthcare in Gaza, these artistic interventions feel like a necessary and urgent reflection on the fragility of reproductive healthcare everywhere right now. Judah concedes, explaining that it was very important to her it felt important to address bodily autonomy and the loss of reproductive rights as loss itself. ‘It’s not just about the loss of a child,’ she says, ‘but it’s a loss of the rights over our bodies.’

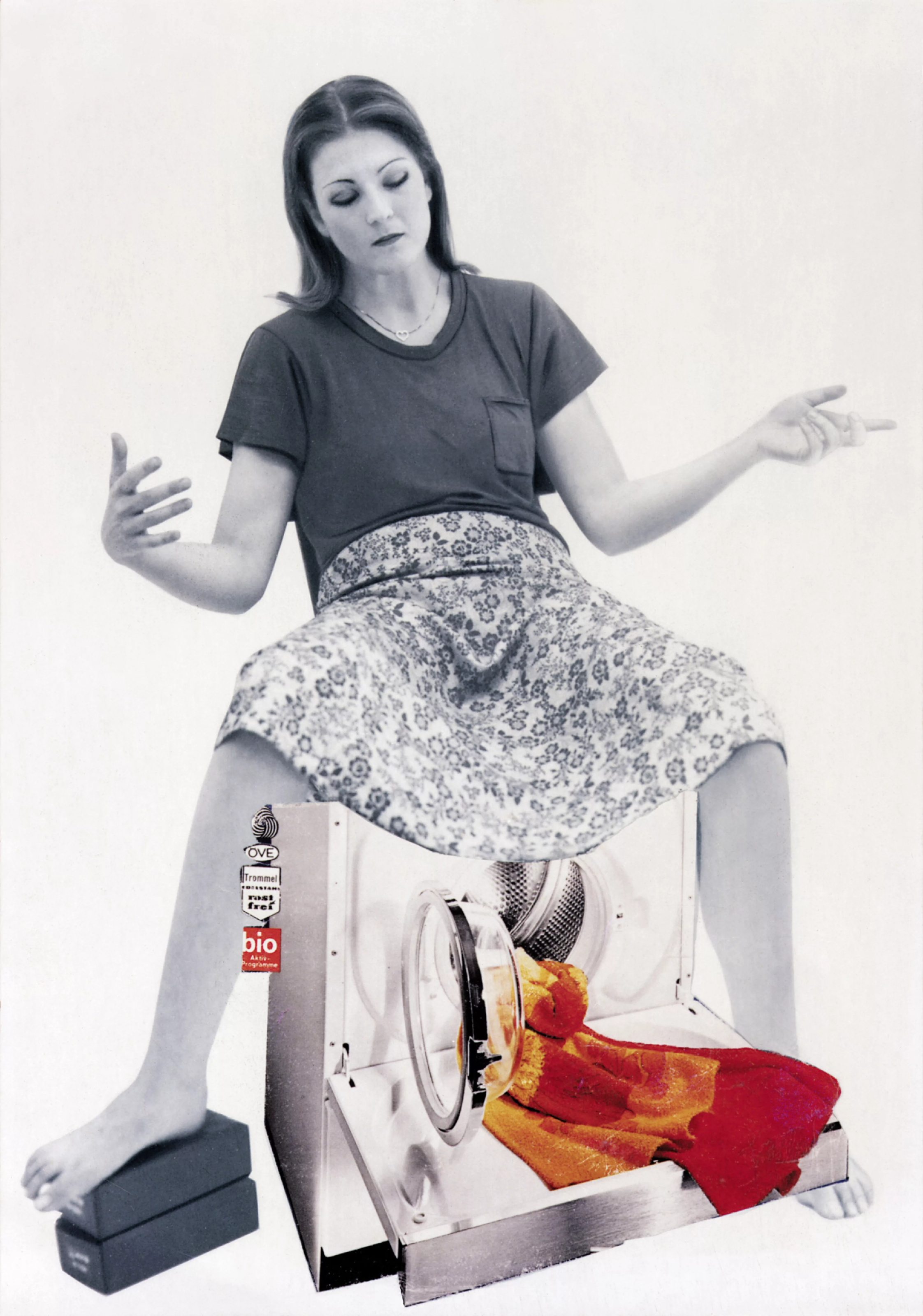

When Judah and I spoke about the overlaps between Acts of Creation and Women in Revolt! at Tate Britain, something that kept coming up was the abundance of art made by activists in both shows. With shows like these there’s a risk of diversity and inclusion feeling performative or tokenistic; art, failing to hold up to its promise of radical praxis; preaching, rather than transforming. But it’s precisely the range of work on show from activists—Artists Campaign to Repeal the 8th, The Hackney Flashers, and Monica Sjöö, to name a few—and their rich history of collective action that makes it such a powerful selection of works. As far as Judah is concerned, activist ephemera—zines, flyers, badges and banners—is ‘proper art’ as much as any other piece on display. ‘People were making art in response to the idea that they could tell their story, that they could share their experiences,’ she says. ‘They felt licence to make art, to write, to make music. But they also felt that they strongly needed to do something to correct the world. It’s very difficult to divide the two, I think.’

It is, however, difficult not to notice the dislocation of Acts of Creation with the wider context of arts institutions, Palestinian censorship, and the ongoing genocide of women, mothers, children, and citizens in Gaza right now. The show’s first outing at the Arnolfini earlier this year was not met without criticism after 1000 artists withdrew their work from the institution after the cancellation of scheduled film and poetry events programmed by Bristol Palestine Film Festival. Helen Charman, academic and author of the forthcoming Mother State, posted that she would not ‘be engaging with an exhibition about mothering—however interesting it might be—that opens, as Acts of Creation does, at the Arnolfini, and so fails to meet the urgent political and ethical demands of the moment.’

This follows a series similar pattern of Palestinian censorship around the UK right now; the Barbican came under fire after it cancelled one of its London Review of Books Winter Lectures by Pankaj Mishra, titled ‘The Shoah after Gaza’. HOME in Manchester cancelled, then reinstated, an event titled ‘Voices of Resilience’ after initial complaints of antisemitism. Though the Arnolfini has since apologised— ‘We believe that freedom of expression and intellectual freedom are vital and must be fully reflected in our policies and practices,’ the institution wrote in a statement; ‘We are sorry that we did not provide a platform for Palestinian voices at such a crucial time’, —it still begs the question of the art’s function, especially in a show so committed to showcasing the potential of art-as-activism and vice versa.

As feminist exhibitions offer space for reflection and dialogue—especially in times of widespread protest and social unrest—art becomes a critical space to address issues like #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, the ongoing atrocities in Israel, Palestine, and Ukraine, and the suppression of women’s freedoms elsewhere. Without a doubt, the best work—most of it, in fact—in Acts of Creation compels us to think about how historical feminist tactics might be employed to confront current crises women, mothers, and people might face: childcare, sexual violence, the exploitation of feminised and domestic labour.

The unfortunate absence of Palestinian artists, mothers, and voices in Acts of Creation can be put down to timing: ‘I’ve been planning the exhibition since 2020,’ Judah says. ‘Hayward Gallery Touring has been on board since 2021 and the loan requests for the show went out in late 2022 through to early 2023 at the latest—everything was laid out and planned far in advance.’ But this omission underscores a broader issue within many public institutions, which often platform progressive views on personal experiences or general historical oppression though falter when addressing urgent real-time crises. As these boundaries become increasingly visible and harder to reconcile, the call for exhibitions to serve as active forms of activism becomes more pressing.

Shows like Acts of Creation, then, signal a need for a more pragmatic and engaged approach to art, emphasising material praxis over speculation—especially given its extensive platforming of artist activists. Moving forward, both curators and institutions—like the Arnolfini, like the Barbican—must push beyond symbolic gestures and towards active, meaningful engagement with the political realities of our time. Only through this can they better fulfill their promise of fostering transformative change, advocating for the rights and recognition of mothers, mother artists, and women worldwide.

Words by Katie Tobin