As London emerges from lockdown and galleries reopen, I find myself increasingly wary of the outside world. Where over the last months I had few choices to make, with exhibitions shuttered and restrictions in place, I am suddenly overwhelmed not only by my own newly regained independence but by a worrying sense of responsibility. Pubs may have reopened, but I still don’t know when I will be able to hug anyone beyond my own household. Like many, I feel bereft of human contact, and of the former pleasure that casual, convivial spaces could offer through the unthinking closeness to strangers. Everything now feels more weighted; venturing out is fraught with personal questions and judgements.

Museums and galleries have, for the most part, continued where they left off, as if their exhibitions had simply been hibernating during this period. Now that they are open once more, it is left up to us as individuals to make our own decisions. The absolute belief in the individual is nothing new in a world driven by neoliberal forces, but it feels more jarring following the networks of care and support that sprung up during the early months of the pandemic. Even as we are increasingly encouraged to come together again in our city’s cultural spaces, we have never been more alone.

“The pandemic has offered an opportunity to consider our interdependencies more deeply, and to take more care, in turn,” Jennifer Schaffer wrote yesterday in The Guardian. “What could a society achieve if it chose to live by a politics of interdependence? What new forms of care could we imagine if we continued to view our individual desires and wellbeing as inextricably bound to the desires and wellbeing of others?” She expresses frustration at new government initiatives to encourage spending, which frame individual economic choice as the most effective way to help our communities.

“Even as we are increasingly encouraged to come together again in our city’s cultural spaces, we have never been more alone”

Within the art world, this focus on the holistic power of commerce is all too familiar. Blockbuster exhibitions, and even entire galleries and museum wings, are notoriously sponsored by banks, oil companies and wealthy individuals—notably the Sacklers, who were exposed last year for their part in the American opioid scandal. Much of the attention drawn to these controversial choices of benefactors has come from the work of protestors and activists, who tirelessly campaigned for the links between these corporate and creative worlds to be severed. BP’s 26-year relationship with the Tate came to an end in 2016, while Shell’s 12-year sponsorship of the National Gallery stopped in 2018.

On Monday 27 July, Tate reopened its galleries for the first time since lockdown. Protestors were waiting outside as the doors were unlocked, many of whom would have been familiar to those working inside the gallery that day. The demonstration was staged by members of Tate’s own staff, who face up to 200 job losses from the commercial arm of the business, Tate Enterprises. “Many of these colleagues will be amongst the lowest-paid staff on the Tate estate, with some at risk earning little more than the national minimum wage, and in some of the most diverse teams across Tate,” said the PCS union.

Meanwhile, Southbank Centre has announced plans to make 400 of its 577 staff redundant this week. The centre will not reopen this year, and has stated that it intends to model itself on a “start-up” when it does in April 2021, with 90 percent of its spaces for rent and only 10 percent for the exhibition of the centre’s own art exhibitions, music performances and literature events—according to an open letter written by current members of staff. It is a shocking proposal, and one that does away with any illusion of creative over commercial interest. The letter, titled #SouthbankSOS, has now been signed by over 6000 people, and emphasises that the proposed redundancies “will disproportionately affect the lowest-paid employees (reducing staff numbers by 63-68% only equates to a reduction in payroll of 30-35%)”. Like at Tate, BAME staff will be the most affected.

“The art world, already a precarious and elitist space that few can afford to enter, looks set to become even smaller“

The devastating effects of the pandemic on the sector are becoming increasingly clear, but there have been few creative solutions offered for an alternative direction that galleries and museums could take. If they are to open for business only in the most literal sense, what hope is left for a creative industry that continues to divide rather than connect its workforce? It is often said that art imitates life, and the commercial interests so heavily championed by the British government, as well as the focus on the individual over community, are plain to see in these institutions.

The art world, already a precarious and elitist space that few can afford to enter, looks set to become even smaller. This week the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York announced that all future internships would now be paid, as a result of a $5m pledged gift from a philanthropist. The Art Newspaper’s headline put it bluntly: “Met interns will cease toiling for no pay”. These are small gains, and serve more to highlight the bleak state of affairs in the industry than something to be applauded. When paid internships at one of the world’s wealthiest and most prestigious galleries must still be fought for in 2020, the imbalance of power seems particularly stark.

It is a divide that is increasingly reflected in London’s skyline, with the concrete skeletons of new constructions blotting the horizon. Commerce is embedded in the city, just as it has worked its way inextricably into its art and culture. Looking out at the changing landscape, I think of Ian Nairn’s London, his 1966 idiosyncratic treatise on the capital. “London burnt in 1940 for the sake of tolerance, and the price was well worth it. It is burning again, but this time only to satisfy developers’ greed, planners’ inadequacy and official stupidity,” he wrote, in a sentiment that feels more relevant now than it ever has. “We must put out the fires and start healing this great place with the love and understanding it needs. It is already three parts gone; for God’s sake let’s leave the rest alone, and help to make the city whole again.”

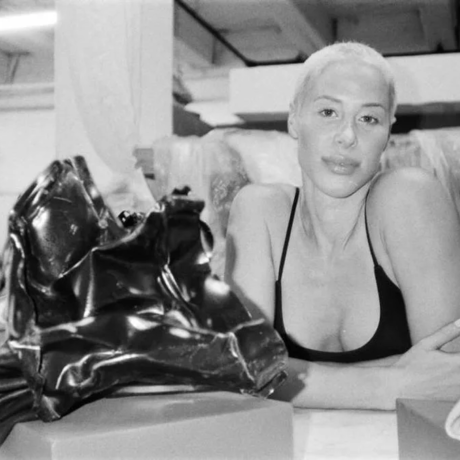

Are We There Yet is a fortnightly column by Louise Benson. Top image © Michael DeLuca