Here’s what to see this month, from Gagosian’s Ashley Bickerton retrospective to Strada’s inaugural exhibition to Austin Martin White’s two concurrent solo shows.

New York – It is only halfway through September, and an overwhelming number of new exhibitions have already opened. This month, successful photographers eschew their commercial acclaim for more daring, personal works — stylized depictions of queer intimacy; figurative painters examine the real and imagined nooks and crannies of domestic spaces; and a new wave of young artists filter the moment through everything from glow-in-the dark fabric to woven tapestries to AI-technology to glitter.

I’ve rounded up some of the shows that I can’t stop talking about, from Gagosian’s posthumous Ashley Bickerton retrospective to Strada’s inaugural exhibition to Austin Martin White’s two concurrent solo shows.

In case you missed it, Mellány Sánchez’s thoughtful sartorial installation “Objects of Permanence” at Abrons Arts Center closed yesterday. Two buzzy exhibitions just opened in Chelsea: Bárbara Sánchez-Kane at Kurimanzutto and Wolfgang Tillmans at David Zwirner, and Magenta Plain unveiled concurrent solo shows for Daniel Boccato and Zach Bruder. If you’re going to openings tonight, head downtown for Sydney Vernon’s debut at Kapp Kapp, before catching two must-see openings ten minutes away at Company Gallery. Then end your night at Lubov Gallery for a performance by fashion designer Gogo Graham. This weekend, check out the shows below and stay tuned for part two later this month. Happy gallery-going!

Nina Hartmann: Soft Power

Silke Lindner, September 8–October 7

In Soft Power, Nina Hartmann has created a new visual lexicon for understanding the inconceivable amount of information, past and present, that exists in the world. Sorting through the abstract symbols is a venture into the artist’s distrust of information and somewhat morbid curiosity. At Silke Lindner, each gallery wall features a large sculptural wax and resin painting collage embedded with inkjet prints and pigments of red, green, yellow, and blue.

The shapes appear at first glance to be iconography lifted from some unknown source: star-like, weapon-like, ancient hieroglyphs or religious symbols. In “Chaos Map” (2023), a faded blue print depicts a man peering through his cupped hands; phrases “subjective experience,” “knowledge production,” “proof/evidence,” and “construction of reality” are underlined by red arrows that cross into an ‘X” at the centre of the hexagram-like shape. Rooted in extensive research into official government texts about topics like nuclear testing and UFOs, Hartmann’s sprawling references are synthesised in collages that both conceal and reveal the information they contain: a mirroring of the way information is disseminated by politicians and other voices of authority today. Good luck trying to differentiate the found photos from the artist’s archive and AI-manipulated images!

Quil Lemons: Quiladelphia

Hannah Traore, September 6–November 4

Quil Lemons’s first solo show with Hannah Traore is a subversive, stylised portrayal of queer intimacy. The large-scale, mostly black-and-white photographs offer an intimate window into the creative mind of Lemons and his community, who are both his muses and his collaborators. Here, vulnerability and strength expand upon and eclipse preconceived notions of race, masculinity, sexuality and gender. Lemons is not documenting from the outside; he is on the inside looking in — reflecting on his own journey of self-discovery as well as that of his chosen family.

In “Thugpop” (2023), a lace-clad Christen Mooney, aka ThugPop, a New York creative and musician, crouches on his toes on a chequered, linoleum floor. A mesh bridal veil is pushed back over his forehead, and a cascade of small, wavy braids drape down his chest. His hands rest on his sheer thigh-high socks, and a rosary hangs from between his lips. ThugPop’s posture is sensual and confident; his gaze commands the room. Elsewhere, subjects similarly meet Lemons’s eye (or trustingly turn their backs): the poses and glances are the product of relationships that are more than skin-deep. While Lemons’s work recalls the boundary-pushing sensibility of earlier queer, erotic photographers like Robert Mapplethorpe, Jimmy DeSana, and Peter Hujar, his vision is uniquely his own. Here, Lemons’s new works step out of the shadow of his impressive commercial catalogue; the result is a powerfully personal artistic practice.

Ashley Bickerton: Susie’s Mother Tongue

Gagosian, September 8–October 14

Ashley Bickerton‘s apocalyptic and humanist vision captures the irony of the modern world, an impressive feat for the late artist whose style continuously shape-shifted over four decades. At Gagosian, Bickerton’s visual language reaches a crescendo; collective desires to consume, explore, and conquer push up against each other. The lines between painting, photography, and sculpture blur. Through a wide range of mediums and subject matter, a boundary-pushing artist with an idiosyncratic vision comes into focus. The survey of the late artist’s practice was initially intended as a career overview. Bickerton selected the works and planned the installation during a visit to New York last year before he passed away from motor neurone disease complications last November.

During the last year of his life, Bickerton created 15 new Blur paintings and sculptures based on photos of loved ones. Even as his condition worsened, he continued to work from his Bali studio. In these effervescent, haunting new works, dots sharply mark the eyes of obscured figures filtered through a hazy, airbrush-like lens. The Blur works provide yet another entry point to the artist’s expansive vision. Last year, two concurrent shows at Lehmann Maupin and O’Flaherty’s put Bickerton on the radar of a new young audience. Now, Gagosian seeks to expand and solidify his legacy. Here, the artist’s ingenuity and sense of humour are on full display.

Jonathan Lyndon Chase: his beard is soft, my hands are empty

Artists Space, September 8–December 2

Jonathan Lyndon Chase finds power in domestic spaces. For their first solo institutional exhibition in New York, Chase transforms Artists Space into a world of their own, a fusion of memory and fantasy. Chase’s work is an ode to their Black queer community and the places where they feel safe: the living room, a barber shop, a laundromat, and the bedroom.

An impressive number of soft sculptures, large-scale paintings, drawings, videos, and poetry fill the entire ground floor (old and new). In “Reclining Waves” (2023), two men sit intertwined, cast in a hot pink and orange glow; one holds his lover’s head in his lap as he brushes his hair. Throughout the exhibition, subjects’ bodies overlap with each other, collapse into each other in tender caresses, and stretch out comfortably within their rooms. In “Pubes, Stretch Marks, Blue Fitted” (2023), a bright red background frames a nude man in a backwards blue cap who is nestled onto a black, throne-like sofa chair; red nail polish, his toes dangle above the ground. A black leather couch faces a table with a figurative sculpture of a nude body as its foundation: “Homie” (2023) is made of, among other things, a “hood chain, nail polish, and glass.” The exhibition offers a sprawling entry point into Chase’s interior world.

Austin Martin White: Familiar Dysphoria

Petzel Gallery, Sept 13–Nov 4

Austin Martin White: Lost in the Sauce

Derek Eller, Sept 5–Oct 7

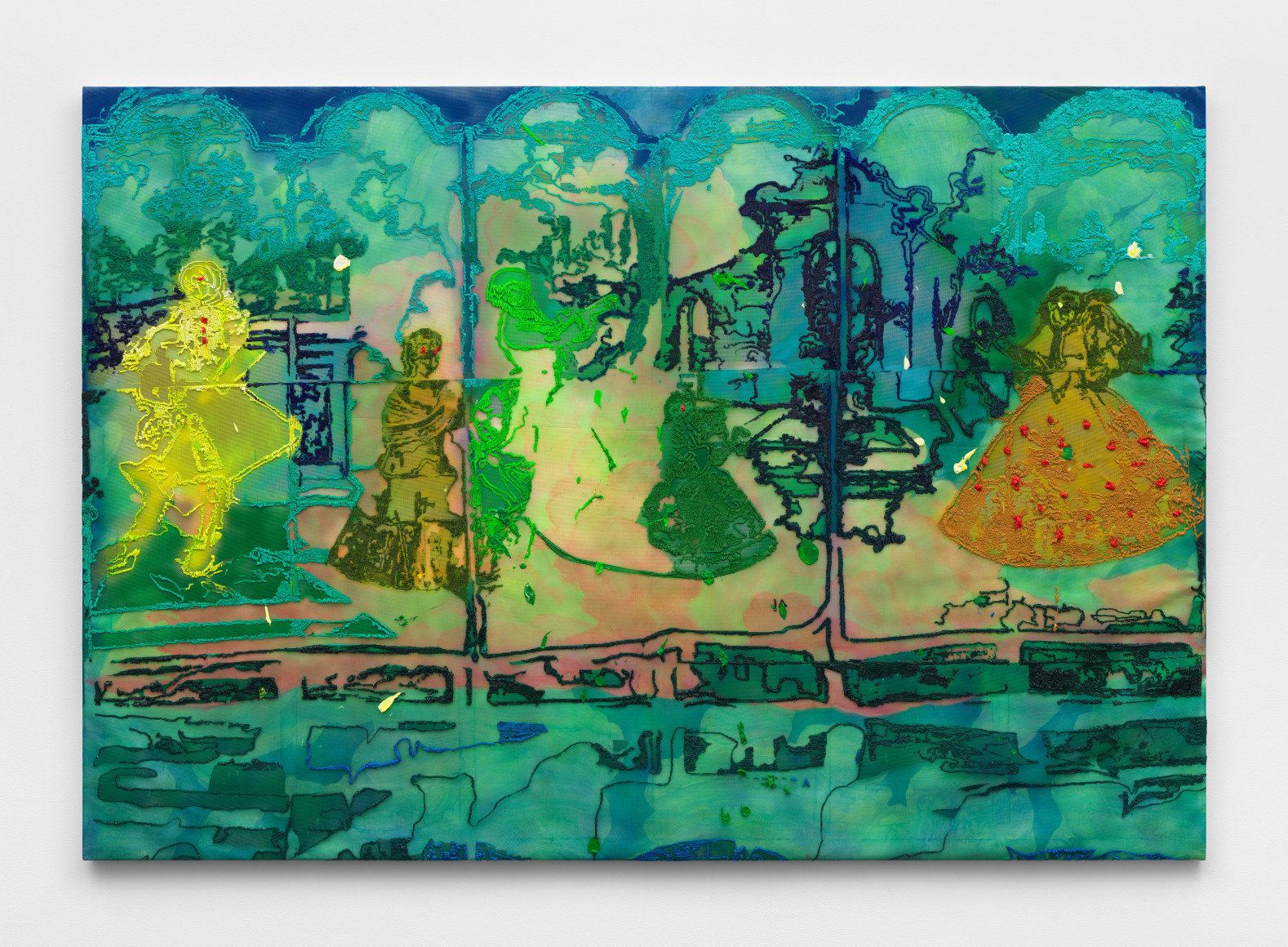

This month, Austin Martin White’s work is on display at two galleries, Derek Eller Gallery and Petzel. In his recent paintings, White investigates the complicated history of 18th-century colonial Mexico — both its cultural and personal significance. The artist spent time researching Mexico’s “casta” paintings, used as a system for classifying individuals by their skin colour. In his works, these idealizations of whiteness are subverted by the use of a vibrant spectrum of colours: reds, neon greens, yellows, and purples fill in the contours of his subjects.

Some works are made on glass mirrors, while others, like “Cloudscape (linear casta)” (2023), include rubber, spray paint, vinyl, reflective fabric, glow-in-the-dark fabric, and nylon mesh. Together, the layered materials probe a deeper inspection beyond the surface. Upon closer look, clusters of raised lines reveal figures at first hidden in the abstracted foreground. The result is a collection of poignant works that simultaneously evoke feelings of belonging and alienation.

Bony Ramirez: TROPICAL APEX

Jeffrey Deitch, September 9–October 21

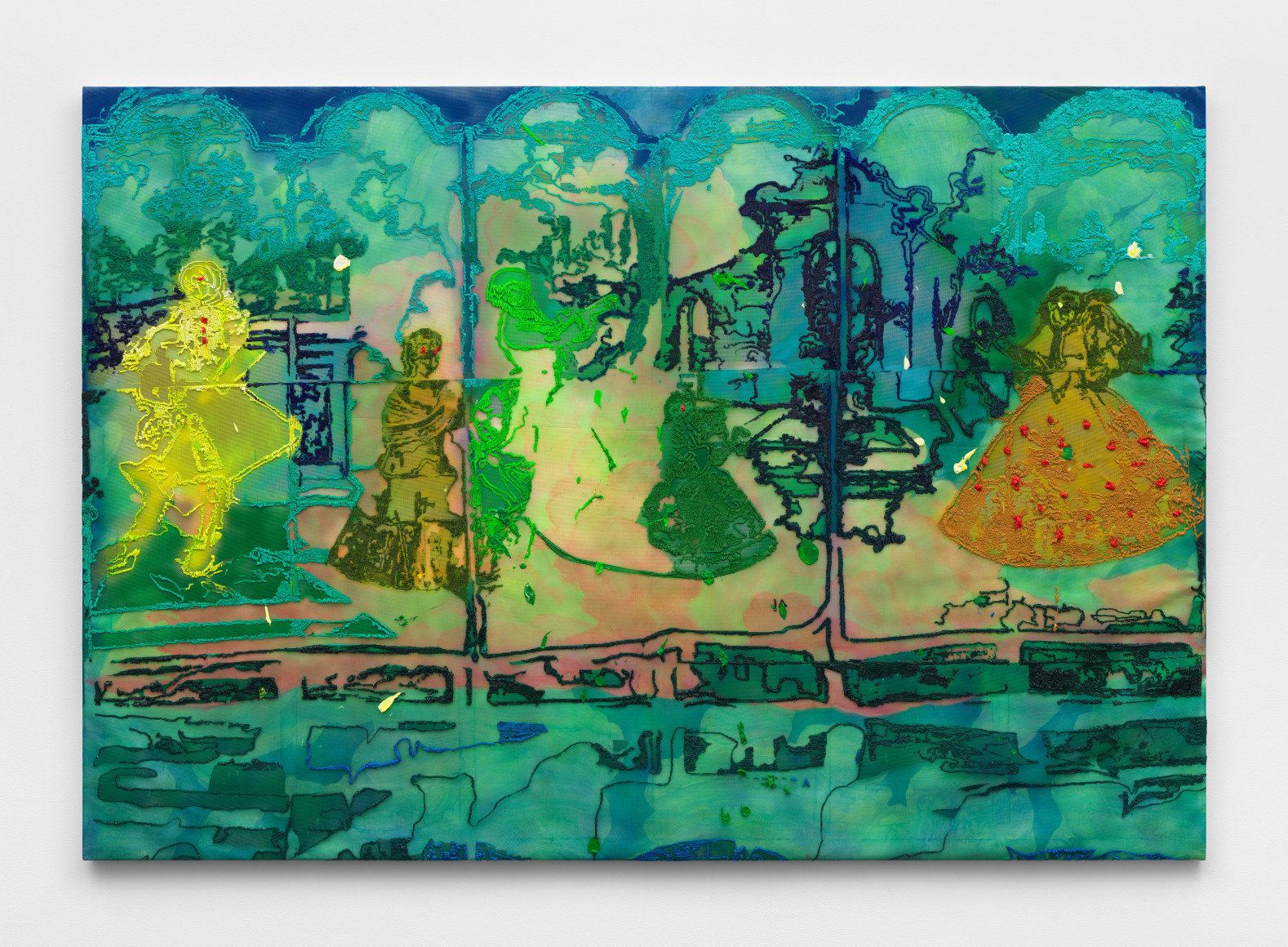

New York City is both a land of displacement and a chosen home; people come here for a better life, to join their families, or because they have nowhere else to go. The city’s culture is indebted to what those who immigrate here bring with them, which is often held dearly to remedy what was left behind. Bony Ramirez came to the United States from the Dominican Republic when he was a 13-year-old. Since then, he has only returned to his motherland through his art, filling in missing rural childhood photos with his moving, colourful works. Ramirez’s sculptures and paintings capture the vibrancy of Caribbean culture as well as the trauma of its colonial past.

The walls at Jeffrey Deitch are painted blood-red, while works are simultaneously spiky and soft. In one painting, a young girl perched on a tree stump raises a chain that holds a severed cow’s head on a hook; blood gushes down the canvas. Taxidermied animal busts (including a cow) are perched on pedestals in the middle of the paintings, and a wooden rooster fighting ring sits in the mezzanine (a reference to one Ramierz’s father had back in the Dominican Republic). In “The Annunciation” (2023), a woman reclines on a tiger’s hide spread across a daybed; English wallpaper lines the wall behind her. A hand holding a seashell reaches from out of the frame to drizzle water down onto her long, wavy black hair. In a surrealist touch, one of her arms is made from a red, flowering vine. Ramirez’s installation is immersive and full of symbolism that extends to the colourful walls and carpets. No matter where you look, you are both confronted and welcomed by the artist’s vibrant memories.

Polina Barskaya: Intimism

Monya Rowe, Sep 7–Oct 21

A solo exhibition of new paintings by Polina Barskaya that underscore the mundane, routine, and candid moments of private life without the normal clutter of a house that has been lived in. Instead, the sense of home is transposed to the subjects. Barskaya has dedicated the last eight years to documenting herself, as well as her husband and child, through her work. Familiar faces in her paintings memorialise inconsequential moments, the pauses between action, and youth — a quality highlighted by the addition of her young daughter in recent years.

The intimacy of her family portraits, often depicted nude or in states of repose, is subverted by the ornate yet nondescript environments of hotels and rental homes where the scenes are set. Barskaya often travels to locations with painting in mind, taking photos to later paint. In a formal living room, Barskaya’s child pensively sits at the edge of her seat; her husband is reclined halfway out of the frame, sunlight revealing the hair on his leg that is sticking out of a white robe. Polina sits front and centre, also robed, leaning slightly forward in a messy bun. Branches and white streaks on the window suggest the only marker of an outside world: it is winter. The vignette seems to be suspended in time, offering a tender meditation on the passage of life.

Embodied Spaces, group show

Strada, reopens Sept 19–Oct 1

A new art gallery just opened in Lower Manhattan after building a name for itself online as an incubator for creatives with pop-up shows. Strada, founded by Paul Hill, made a splash in the scene last week with a buzzy opening that drew out a crowd that lined up around the block. The first exhibition, a group show titled “Embodied Spaces: The Body as Architecture” (2023) featured a group of rising stars in the art world: textile artist Qualeasha Wood and fashion designer Tia Adeola, and painters Milo Davis, Augustina Wang, Thomias Radin, and Obi Agwam.

In her intricate tapestry “C’est La Vie,” Wood weaves together internet culture and personal identity to comment on how Black women are consumed in popular culture. Wood’s work opens a dialogue that is expanded upon by the rest of the works in the show. Dynamics between the body and how it moves throughout constructed dimensions are explored through clothes worn and spaces occupied.

From Sept 13 – 15, “Embodied Spaces” will take an intermission for two exhibitions: “Home as Corpus,” curated by Diallo Simon-Ponte, and “Lovers and Friends,” curated by Sophia Wilson Iza El Nems.

Dreaming of Home, group show

Leslie Lohman Museum, Sept 7–Jan 7

Angeles, and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

“Dreaming of Home” at the Leslie Lohman Museum examines the public and private dualities of queer life. With works alternating from tender to exuberant, the group show is framed around, or born from, Catherine Opie’s seminal photograph “Self-Portrait/Cutting” (1993). In “Self-Portrait/Cutting,” Opie faces an ornate emerald green wallpaper; her back towards the audience. Transformed into a canvas, a picturesque scene is carved into her flesh: two stick figures hold hands (their skirts are their only identifier) in front of a small house and a partly cloudy sky.

Thirty years later, 20 artists, including Cajsa von Zeipel, Clifford Prince King, Jenna Gribbon, Nicole Eisenman, and Rene Matić, expand on Opie’s nuanced portrayal of the queer body, imagining, recreating, and questioning domestic refuge. This exhibition is more important than ever at a time when anti-LGBTQIA+ legislation is rapidly advancing in the United States. Leslie Lohman offers a safe space to explore the many facets of queer life then and now.

Awol Erizku: Delirium of Agony

Sean Kelly, September 8–October 21

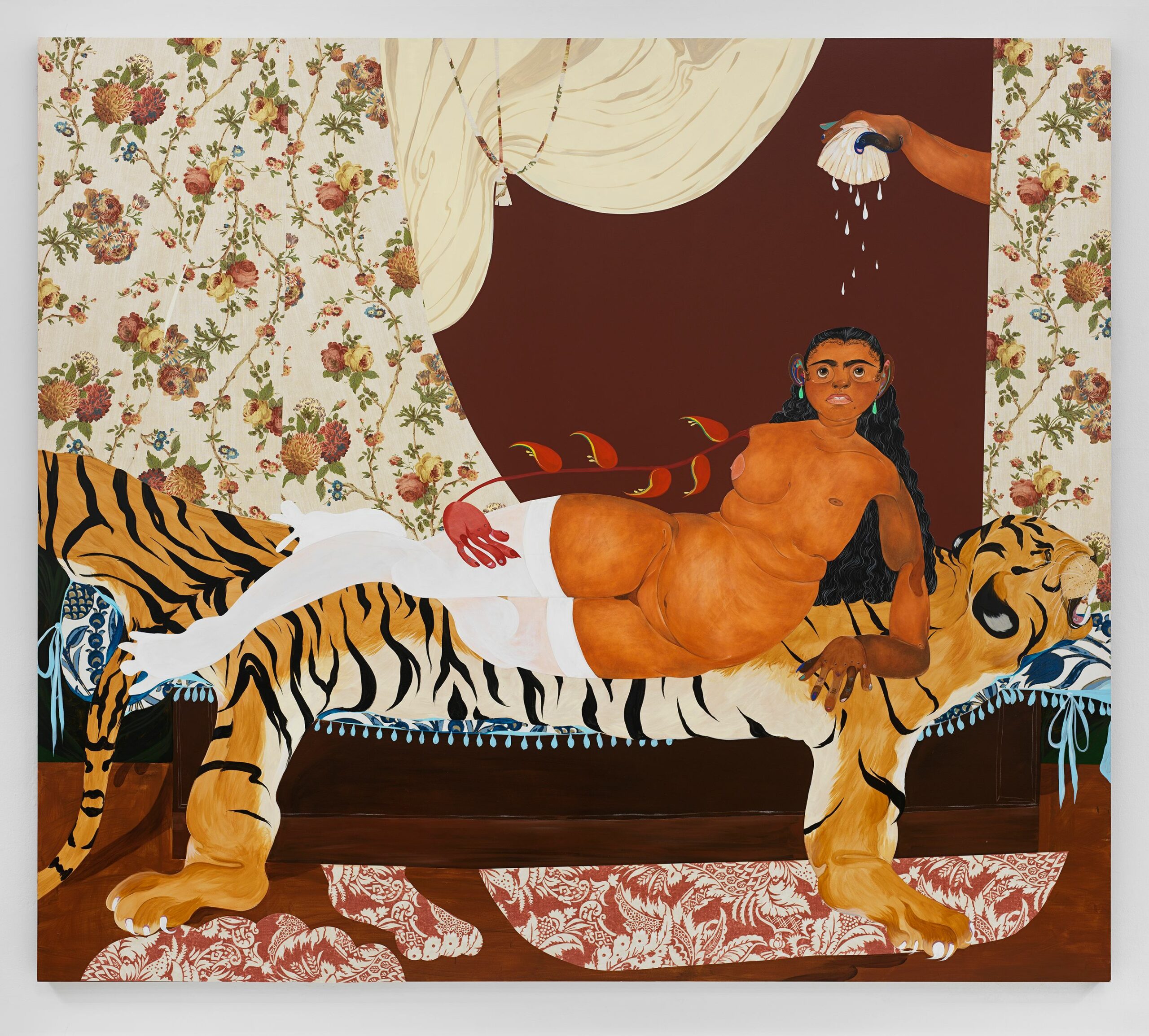

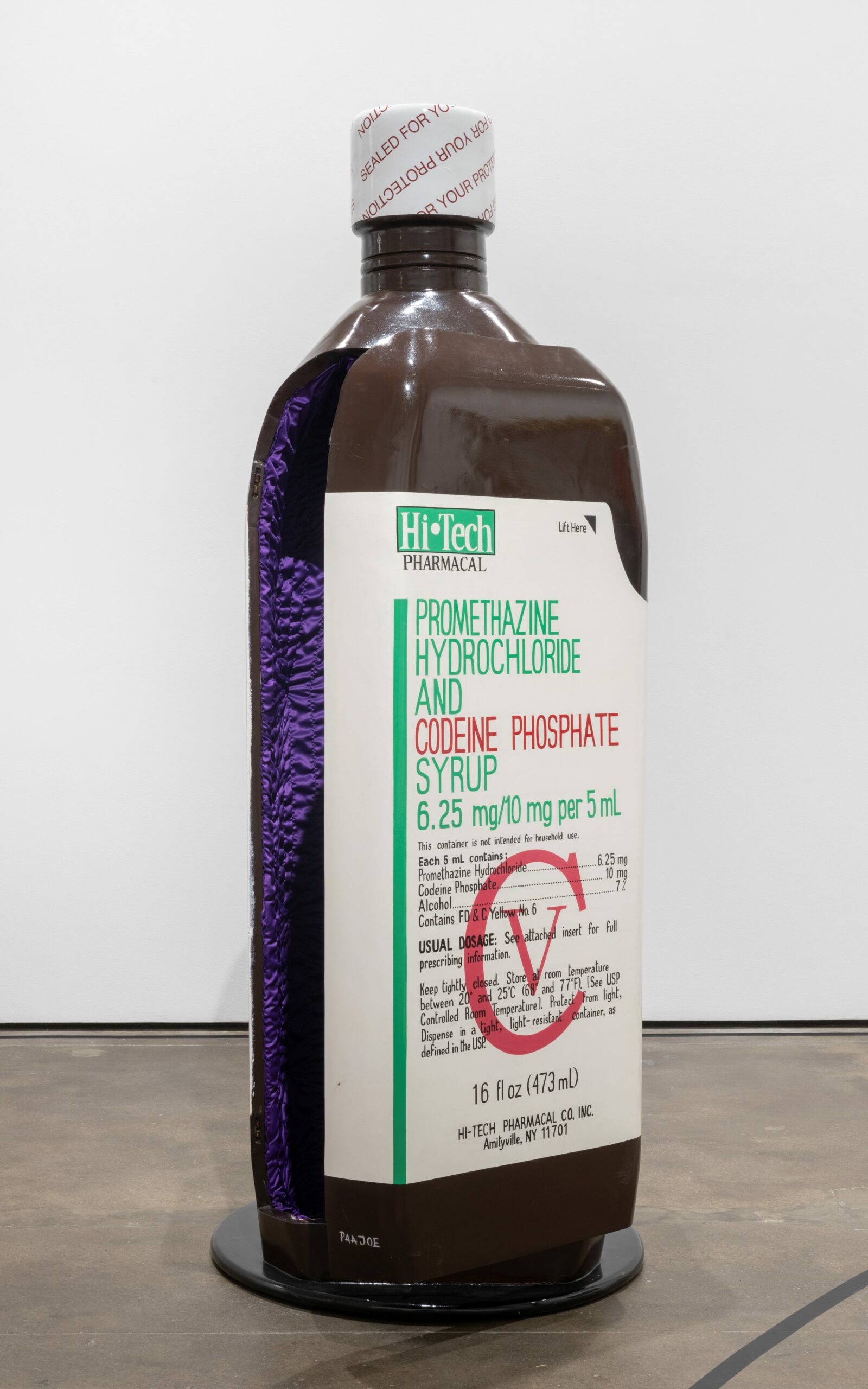

Awol Erizku’s first solo exhibition at Sean Kelly, New York, is a love letter to the linguistic power of rap music: the acerbic and aerobic wordplay of musicians like Nas that offers two or three meanings with every turn of phrase. In “Delirium of Agony,” the multi-disciplinary artist (who is also a successful DJ) translates this duality of language through painting, sculpture, photography, incense drawings, and assemblage.

Erizku’s lexicon is varied yet pointed, an agglomeration of symbols from hip-hop, art history, street culture, and sports that uplifts and expands upon public displays of Black identity. A standout work is a large coffin disguised as a realistic-looking bottle of lean made in collaboration with legendary Ghanaian coffin maker Paa Joe. Another one of the Ethiopia-born artist’s sculptures configures three basketball hoops as a pan-African flag. Throughout his career, Erizku has continued to find new ways to translate his cosmic worldview that is grounded in community. At Sean Kelly, Erizku offers the most comprehensive display of his vision yet.

Fred Eversley: Parabolic Light

Doris C. Freedman Plaza, Central Park, Sep 7, 2023–Aug 25, 2024

Last week, Public Art Fund unveiled Fred Eversley’s luminous, 12-foot sculpture “Parabolic Light” (2023) at the Doris C. Freedman Plaza in Central Park, where it will remain for a year. The sculpture is the product of the Light and Space pioneer’s lifelong fascination with the parabola (a U-shaped curve and singular shape that focuses all energy on a single point). It is the largest cast resin work Eversley has made and his first-ever public artwork.

Depending on the angle and the time of day, pink-hued light streams from the translucent fuchsia tower and scatters in a stripe across the concrete. “Parabolic Light” reflects and distorts city skyscrapers, the tree-lined street, cloudy skies, and the peering eyes of spectators.

Jack Pierson: Pomegranates

Lisson Gallery, Sept 7–Oct 14

Photography (and the desire to capture everyday life) is at the heart of Jack Pierson’s installation. In the last three decades, the artist has developed a singular vision that carries across photography, writing, and assemblage. At Lisson Gallery, Pierson’s moving portraits are underscored by collages, sculptures, and various tableaus of ephemera. Here, everything is boiled down to its purest form, like “Bed Springs” (2023), which is made of its namesake. Recent photographs like “Jacob B” (2020) show Pierson opting for the white, blank canvas of a studio as opposed to the evocative landscapes of his earlier photos. Instead, the scenery materialises outside the frame.

Driftwood hangs from the ceiling; photographs, drawings, and magazine pages are pinned in collages to metal panels; words are spelled out in metal letters on the walls. A white cabinet holds neat stacks of towels, and various found tchotchkes are displayed atop silver plywood structures. The sculptural works might be seen as stand-ins for set design or location when viewed as a whole. Or as stand-ins for words to express sentiments of queer desire and nostalgia. In some instances, the language is literal: metal letters that spell out “Real Life” are emblazoned on one wall. As the exhibition winds from room to room, the images and objects build a dialogue that finds the beauty in intimate, oft-overlooked moments of daily life.

Also on view at Lisson Gallery is Laure Prouvost’s solo show “Stranded By Your Side,” which features a standout, sprawling bronze octopus sculpture that engulfs much of the gallery floor.

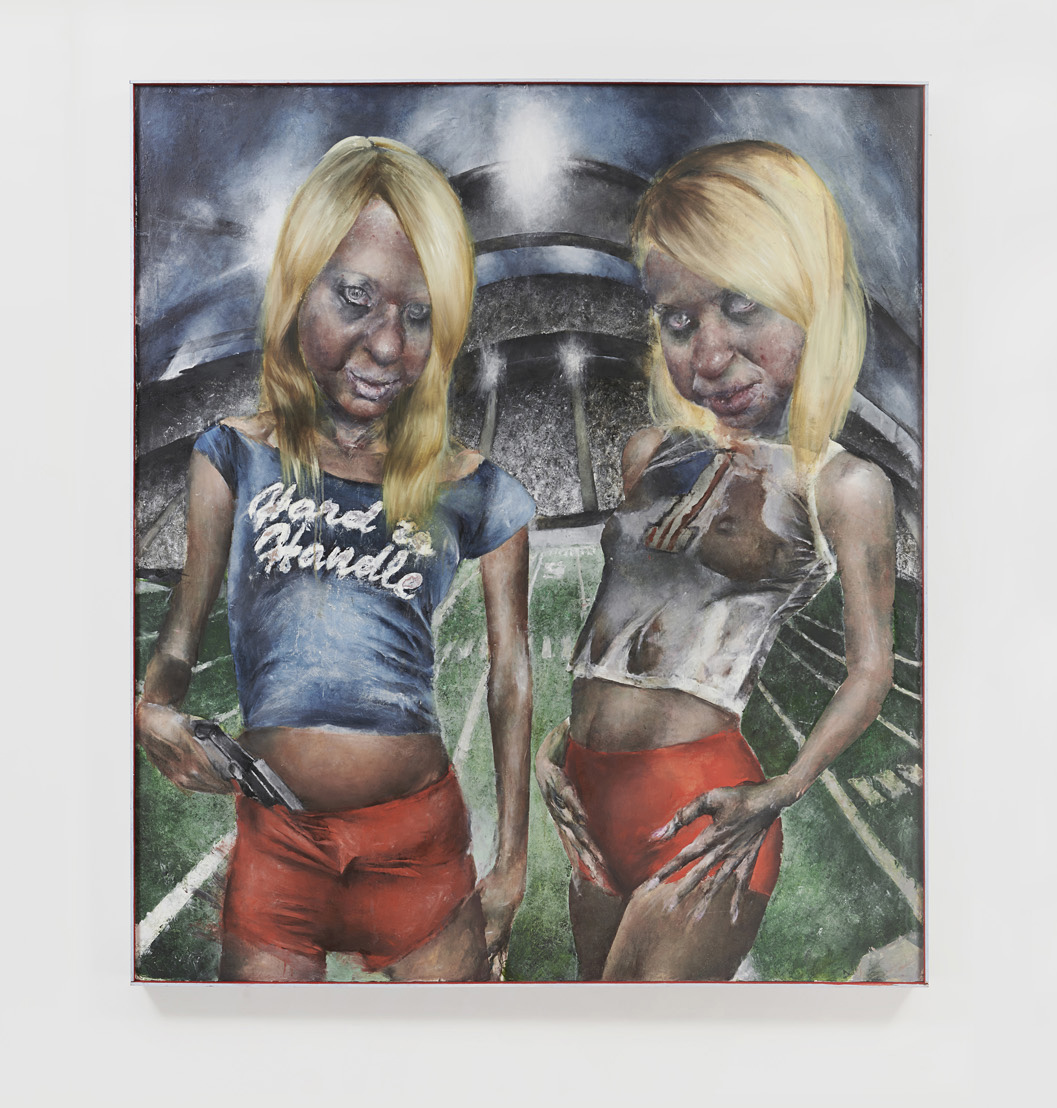

Catherine Mulligan: Bad Girls Club

Tara Downs Gallery, Sept 8–Oct 14

Like Oscar Wilde’s portrait of Dorian Gray, the women in Catherine Mulligan’s paintings seem to have aged and degraded, accruing a gritty sheen, while their Y2K likeness is repurposed and transposed onto a new generation in a commercial revival. A shuttered shopping mall storefront and vacant buildings like “Big Brother House (Pool)” (2023), suggest that while the rest of the world has turned its attention elsewhere, Mulligan is still watching, finding fertile ground for her work.

Despite their perverse, off-kilter appearance, Mulligan’s subjects rock their hot shorts and metallic bodycon dresses with a sensual confidence; they seem to be feeling themselves. Any discomfort felt by the viewer, the paintings seem to suggest, is a reflection of outside expectations. Why do we expect these women to be perfectly smooth and shiny? Don’t we see that enough online and in advertisements? There is something captivating, and dare I say, sexy about the botched and blemished women suggestively clutching their curves (and in once case, a gun). Mulligan’s bad girls are a welcome reprieve to the perfect, rose-colored depictions of “simpler times” and mid-2000’s nostalgia.

Written by Meka Boyle