“An artist, a critic, a curator and a dealer walk into a bar,” I said. “The dealer buys the first round and starts a tab. The artist is broke, so when his round comes he signs his empty glass and gives it to the dealer, who shouts him the drinks. The critic is broke, so when his round comes he writes a piece on the glass as a major new work of neo-dadaist conceptual art. The dealer goes to the bar. The curator is also skint, so when her round comes she promises to include the glass in a survey at the museum. The dealer tells the barman to bring four more. When the time comes for his round, the dealer sells the glass to the Louvre Abu Dhabi and pays the tab out of the artist’s share.”

“That’s not funny,” said the artist to whom I was telling this joke.

“You’re telling me,” I said.

We were stood together in a queue stretching down the side of an abandoned bicycle factory. The building had until recently hosted a charismatic church with barred windows around which children would gather on Sunday mornings to watch congregants channel the spirit of the Lord. I knew this because I used to live around the corner, in a part of London that people including the artist and me had despite ourselves gentrified to the point that we could no longer afford to live there. The rent increases for which we were indirectly responsible, allied to the charismatic pastor’s failure to declare unto the tax authorities what was due unto the tax authorities, had hastened the building’s inevitable conversion into a space for contemporary art. Opening tonight was a new exhibition by a young French artist.

“An artist, a critic, a curator and a dealer walk into a bar…”

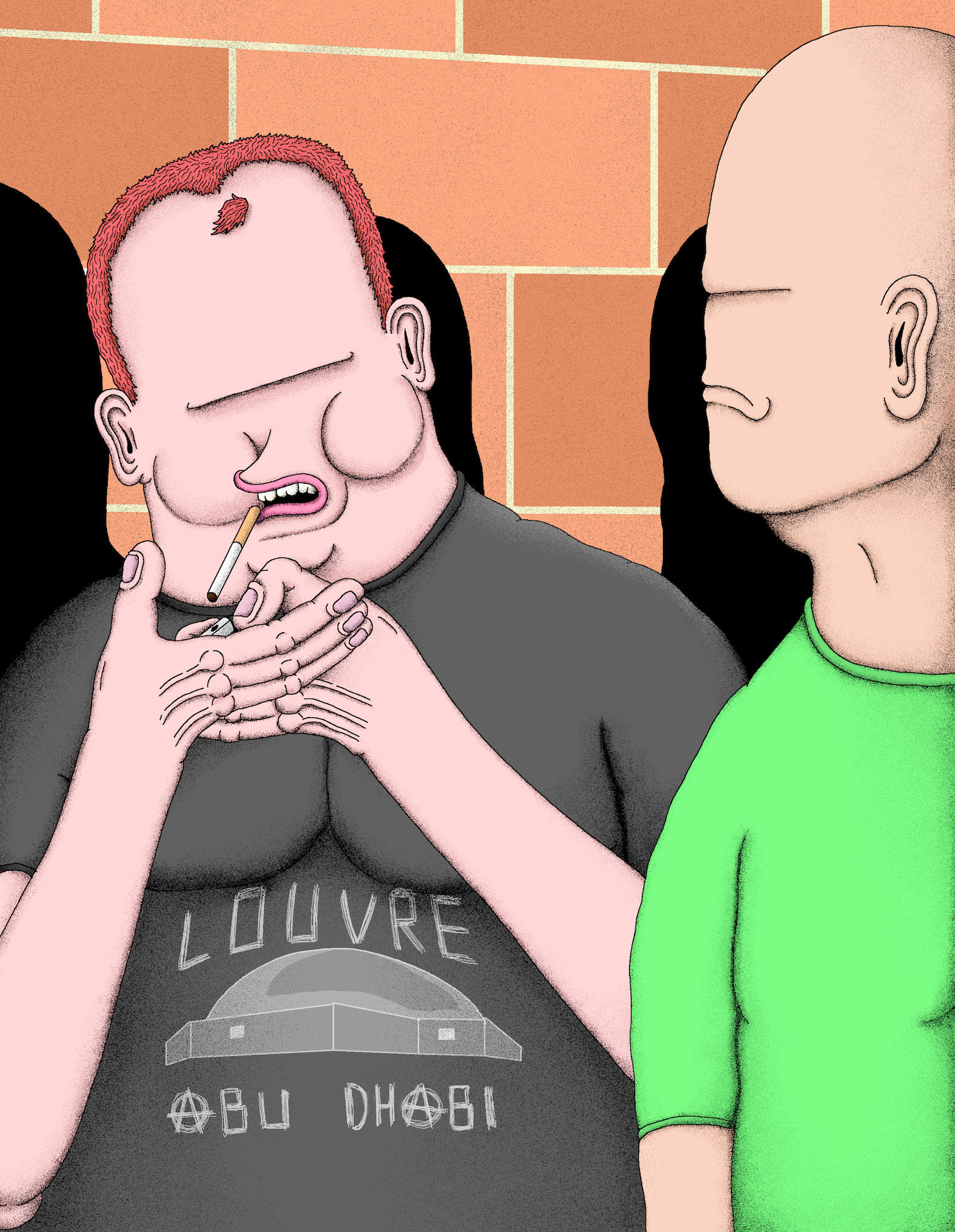

“They are all parasites,” said the artist, Jake, who was wearing a t-shirt reproducing the front cover of an album by a 1980s punk band in defiance of the fact that he is a balding man in his mid-thirties who had recently purchased an apartment with money inherited from an aunt who I had learned was a marmalade magnate. This was broadly speaking the response to the joke I had anticipated from Jake, who considers all other artists to be rivals, any commercially viable enterprise immoral, and every exhibition a hostile act. It was a provocation more than a joke, in all honesty.

“But you are an artist,” I said, “so you’re a parasite?”

“No, because I wouldn’t take the dealer’s money,” Jake said.

“Every professional artist takes the dealer’s money,” I pointed out, “that’s how it works. I went to your most recent exhibition, which was at a commercial gallery. You accepted the dealer’s financial support to produce a show, works from which were made available for purchase by collectors, on the assumption that both you and the dealer would turn a profit. That’s kind of the point of the joke.”

“No, because the gesture described in your ‘joke’,” actual air quotes here, “was motivated by money rather than facilitated by it. The money comes before the idea. The fact that it sells doesn’t make it art. That is the point of the joke.”

“I literally just made up the joke standing in this queue,” I said, “so I get to decide what the point is.”

Jake repeated this back to me in an affronted toddler’s voice—“No, I get to decide what the point is!”—while rubbing his eyes with the backs of his hands to smudge away hot, imaginary tears. “Actually,” in his own voice now, “the point of the joke is that you don’t get to decide the point of the joke, any more than the artist and critic and curator and dealer get to say what has value.”

“Every professional artist takes the dealer’s money, that’s how it works”

“So who does, then?” I said. “How else is it possible to identify a work of art in this age beyond taking it on trust from the artist and representatives of the art world? If I encountered your sculptures in the street, I would think they were junk.” This is literally true—Jake’s oeuvre includes items retrieved from squats cleared by the police on behalf of property developers—but I relished the double entendre. “Or we could look at it the other way. How do I know that the lines on the tarmac over there are to separate parked cars, not an experiment in landscape painting?”

“What difference does it make? Why shouldn’t you get a kick out of the road markings? Why not think of them as paintings? The kind of experiences you’re so determined to reserve for art can happen at any time, in any place, if you allow them to. But you want everything to be carefully sealed off in its own experiential category, neatly labelled as ‘art’—to be pontificated over—or “not art”—to be ignored. I can see you standing in the middle of the road, having a crisis,” here he impersonated me again, this time as a German art historian, “‘I’m getting an unsanctioned emotional and intellectual response to these minimalist line markings! I’m having an unmediated experience! Help!’”

I was laughing. A man in a black hoodie and tether tracksuit bottoms took the handle of the concertina gate marking the entrance to the gallery at its right edge and dragged it along a track cut into the concrete, crumpling the shutters together. Cupping his hands, Jake lit a cigarette whose tip flared briefly up over the tops of his curled fingers. We walked forwards.

This feature originally appeared in issue 34

BUY ISSUE 34