Theaster Gates needs little by way of introduction. He is perhaps best known for the Dorchester Projects, which has seen the renovation of multiple buildings on Chicago’s South Side for use in a host of community-driven initiatives with the aim of providing a “model for greater cultural and socio-economic renewal”.

Having studied the unusual combination of Urban Planning and Ceramics at Iowa State University, before going on to do Fine Arts and Religious Studies in Cape Town, Gates’s expansive practice now is an enticing mix of these different elements: socially aware, highly respectful of local craft and, perhaps most importantly, gigantic in scale and ambition. He has always felt like an artist who slipped in through the side door, aligning himself more with the ordinary people who breathe life into his projects than contemporary art scenesters.

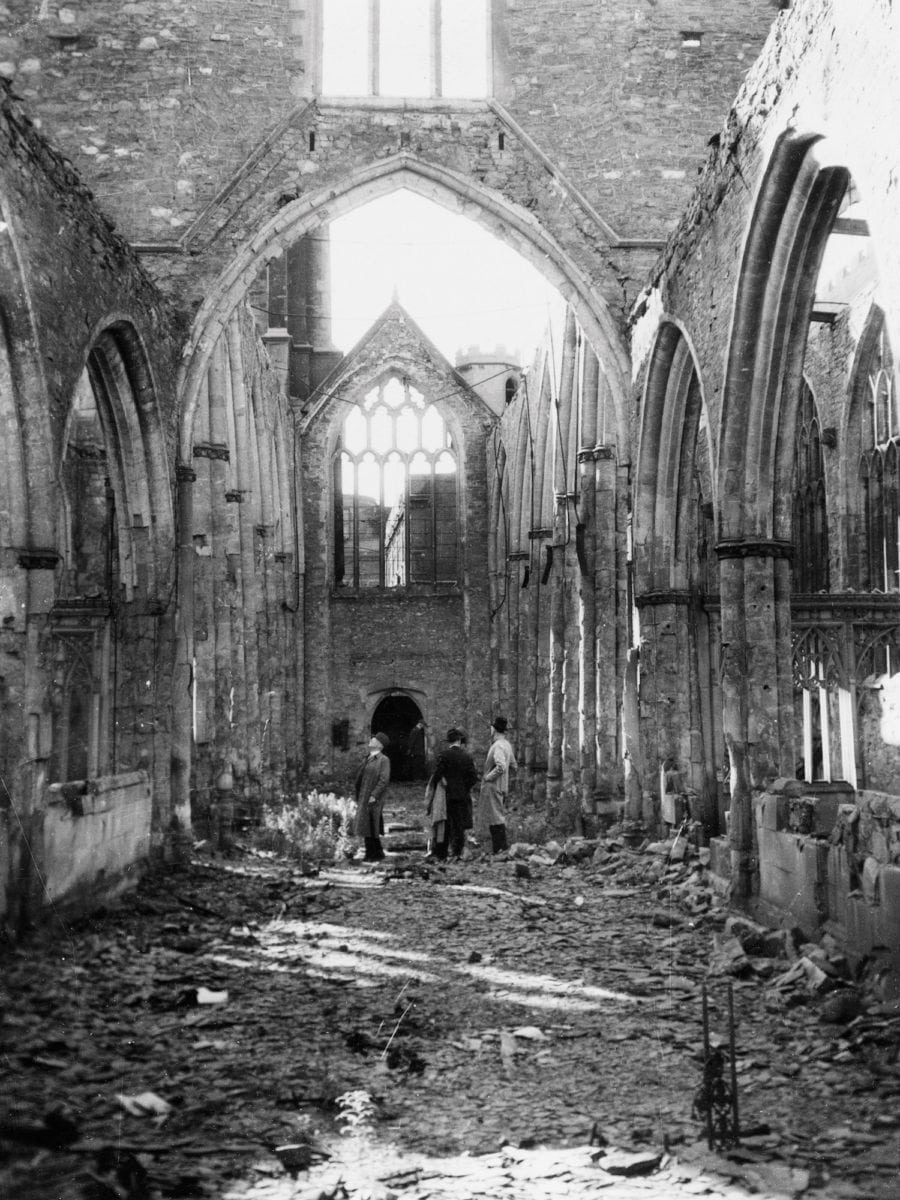

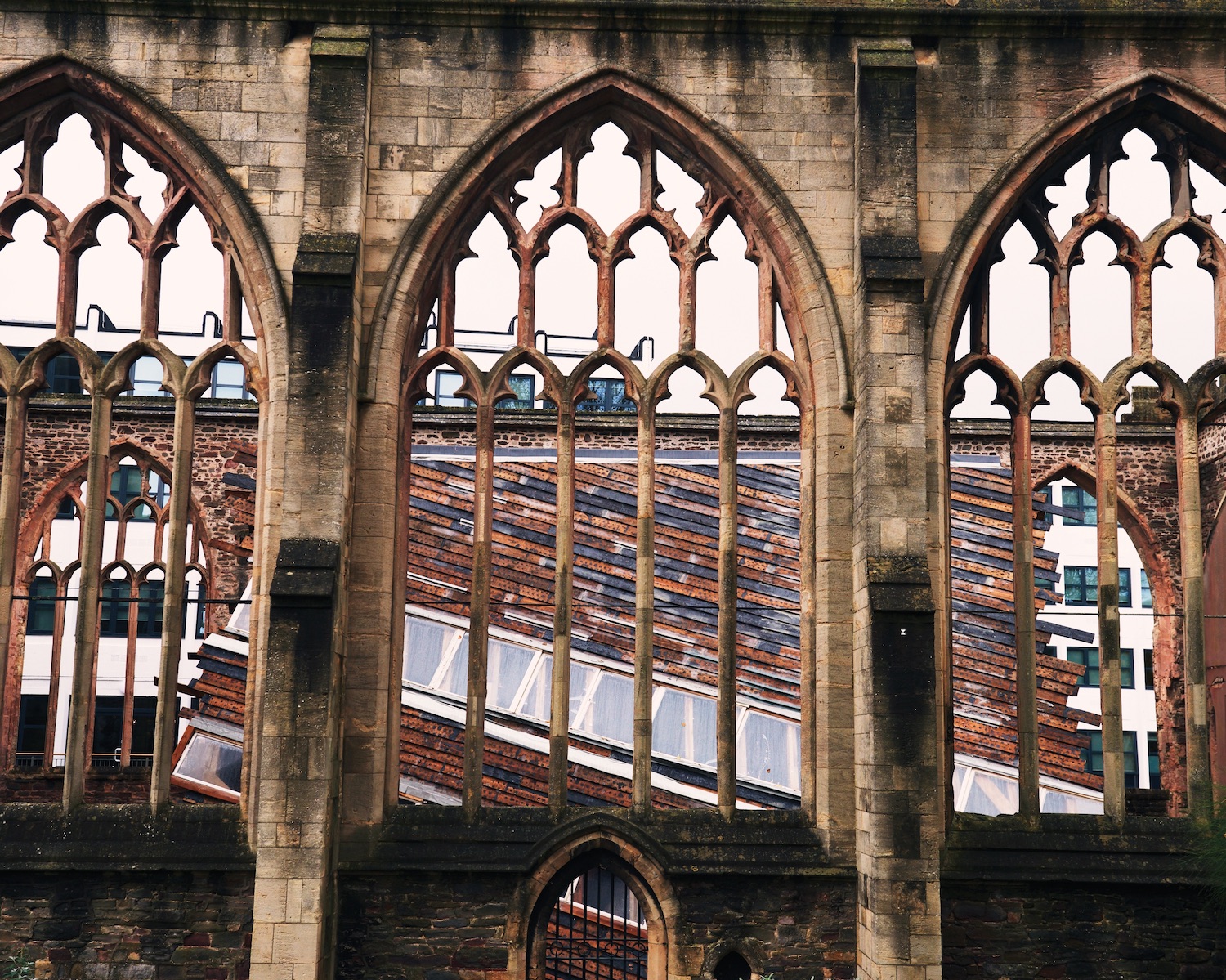

In late 2015 Gates launched Sanctum, a 24-hour, 24-day programme of sound, located in Bristol, in the south-west of England, inside the ruins of Temple Church—a bombed out fourteenth-century site that had, until this point, been off-limits for seventy-five years—with the intention of “amplifying the city”.

“My part was really language-based,” he tells me as we meet in the autumnal, overcast grounds of Temple Church on Sanctum’s first morning. “In this project, more than in any project, my goal was to be as light as possible. What I wanted to do was give it direction and motivation, and give it the perimeters by which as many people besides myself could be involved.

“In a way, Sanctum could have been a small sound installation coming out of the ruins, or it could have been what it is, which is an architectural work that acts as a platform for the city. That’s all in language, as in: ‘Is it a this, or a that? I think it’s a that.’ And then you have to kind of write that out, and you have to have a team that has the capacity to deliver that. It’s been a very different process but I’ve fallen in love with the project and feel very strongly about the voices that I’ve heard already.”

I arrive to find the English Heritage site alive with activity on opening night. A wooden coffee truck serves warm drinks to the crowds; performers who haven’t yet had their turn wait in an outside seating area, on chunky halves of log that are laid out as benches. The temporary triangular structure that sits within the four walls of the ruin is utterly Gates in aesthetic—a rough-and-ready selection of rustic wood panels, bricks and windows from the Salvation Army and old Bristolian houses cobbled together in a manner that looks terrifically, effortlessly beautiful. Within, a local musician delicately plucks “Stairway to Heaven” on a harp in front of a crowd of thirty or so. Already, it feels like a project that exists beyond the artist.

Gates’s most revered works tend to begin, as he says, in the sphere of language, he keeps the hands-on nature of social, local-level craft thriving through his collaborators and performers. “I have a sweet spot for the craftsman,” he tells me. Indeed, while much of our discussion revolves around the conceptual nature of his own role in the project, Sanctum itself has a raw feel. From the flaking timber of the external structure to the invitation to handle lumps of raw clay mid-afternoon and the warm pits glowing in the corners, at times as an experience it’s more akin to a folk festival than a contemporary art event.

“All of a sudden you realize that these are the hang-ups that we have that create the hierarchies of access”

“I asked: ‘Who are the builders?’ There was all this amazing craft and guild stuff in Bristol, there were all these clay deposits that were here and we met these young boatmakers who were from a line of shipbuilders, who were using the same sheds that had been built for these complicated vessels that were moving around the world. We became very interested in them and in returning to these original things.

“Initially, I thought we should have the highest calibre of people performing: ‘We want excellence and we want people to come out and hear excellence.’ Well, that’s restrictive! By whose rubric of excellence? All of a sudden you realize that these are the hang-ups that we have that create the hierarchies of access. So you think: ‘No, let’s just decide that people must do the most excellent job that is possible in their capacity, everyone is invited and they should try to be as excellent as possible.’ And that feels good.”

- Right: Temple Church after the German Bombing of 24 November 1940

Of course, the work does not just live within the artist, his collaborators and the performers, it is also about the public. But when work relies on people—not just on “art-world” people, but on real, solid, public people—how does one reach them? When Gates calls, the art crowd comes running, but the real intention, it has always seemed, is to reach beyond that privileged sphere.

“In order to have a sophisticated enough invitation you need people who can go out and do the inviting. I think the challenges that museums have sometimes, or the challenge of culturally specific things, is that they already have a sense of who their audiences are and you use this word ‘targeted’ and you target these audiences. But what if you lose the target? There’s no way that I, by myself, can do all that inviting. You need an arsenal of people who have tentacles. So there is that intentionality of invitation. It’s not the architecture, it’s not the artist that people know. Bristol said yes to this invitation and now there are all these amazing people who get to meet each other and participate. And it doesn’t feel like they’re participating towards my grand success.’

“There’s no way that I, by myself, can do all that inviting. You need an arsenal of people who have tentacles. So there is that intentionality of invitation. It’s not the architecture, it’s not the artist that people know. Bristol said yes to this invitation and now there are all these amazing people who get to meet each other and participate. And it doesn’t feel like they’re participating towards my grand success.”

“There’s no way that I, by myself, can do all that inviting. You need an arsenal of people who have tentacles”

Over its twenty-four days, Sanctum called on more than a thousand local artists to create sound, in the loosest sense: from 1 am drag shows to performance pottery and early morning calls to prayer. Gates himself appeared on opening night—having flown in directly from delivering a lecture in his role as professor in the Department of Visual Art and Director of Arts and Public Life at the University of Chicago—and left five days later.

It was Claire Doherty, from Bristol’s Situations, an arts organization that focuses on new means of creating public art, who first brought Gates to the project. Speaking to me at the end of Sanctum’s run, she said: “He had this initial vision and we worked very closely with him to put ideas in. He had very strong aesthetic control, which you can see, and then really it was once we agreed a set of principles about programming that he was very happy to let go. He kept in regular touch and we kept sending him movies from it and remarks. But he was like a theatre director, where once it’s running he leaves it in our hands.”

Perhaps this new approach spells the beginning of a Gates franchise, as it were. There has been discussion that Sanctum could move later this year to Essen in Germany, as part of the Ruhrtriennale. It is a difficult thing to imagine, Sanctum being—as every Gates project of this kind is—so locked into the essence of its city of origin. It thrives on the nuances of place, and of breathing life into that specific space: the geographical, historical, cultural and social space of Bristol. How does he feel this kind of move would work? “It’s more like: How do you take a moment to invest in the creation of something sacred? Depending on how you define sacred—for me sacred has to do with people coming together to enact something for no other reason than to give pleasure to each other. Maybe Sanctum has this freedom, to be born in Bristol and then be an emissary of sacred light in other places. Maybe an expanded sense of site could mean that site is the location of an ideology or a set of ideals.”

Temple Church itself has now been closed again to visitors, and the physical structure has been removed. Gates hasn’t been back to the city, but Doherty has been there throughout. As eyes on the ground, I wondered if this impact was ongoing. “Interestingly, [the local theatre] Bristol Old Vic just announced that part of their 250th anniversary next year will be an open stage, where anyone who wants to perform, can. I think an interesting thing that’s happening is the opening up of these cultural institutions. They just seem to have been given a bit of rocket fuel. I think in many ways, perhaps it’s just a part of a renewed confidence in the city to do things differently.”

Gates’s wider intention does certainly seem to be that of setting an example, something he does whenever he comes close to the contemporary art scene. He shared the prize booty of his 2015 £40,000 Artes Mundi win with his nine fellow shortlisted artists. When his practice involves a more typical understanding of physical artworks—paintings and sculptures— they are always wrapped up in a wider sense of humanity. His famous tar paintings—commanding in the manner of the best modernist painting, almost Rothko-esque in aura—are in fact the result of a working session with his ex-roofer father. They created the works together, using his father’s old tar kettle. These humane, warm, loaded pieces are purchased as high art, and the proceeds are fed back into meaty, people-driven projects. In 2013 he pulled the marble tiles from the bathroom wall of a crumbling 1920s Chicago bank building—now the Stony Island Art Bank—and created Bank Bond, a series of $5,000 tiles, engraved with the phrase “In art we trust”. The profits were reinvested into the $45m renovation of the building, which is currently used as a residency location for artists and scholars, as well as a site for artist commissions and exhibitions.

Does he feel that the art world is opening up to the possibility of a more meaningful exchange of values; one that prefers action to gesture? “Well, I love to imagine that there are many art worlds, and this thing that we are seeing as the art world—this complicated little ball of fire that we love to hit with a stick—is actually much broader, it’s fatty, it’s wonky. It actually doesn’t know what it is. It doesn’t know itself.

“Artists have always been engaged in interruptions that are broad and big and too ambitious. Maybe there’s this core art world that will always think about master paintings and what happens in museums and the possibility of collecting great works, the market. These things will always, to some degree or other, be there. I think what artists are starting to demonstrate more and more is that there is room for a much broader and bigger art world. My hope is that what had been a small ball of fire would grow. And so maybe these are all just attempts that demonstrate that you don’t have to compromise the conceptual rigour to make room for more people.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 26

BUY ISSUE 26