Perhaps it’s a hint to the darkness lurking within each of us, or a sign that we’re all seeking some sort of meaning in these confusing and strange times, but most of us surely have something of a fascination with the occult and the rituals surrounding such practices. In secular times, and even in more gnostic ones, artists have long been drawn to such themes.

The current group show, titled A Charm Against All That, at Projects+Gallery in St. Louis, Missouri, brings together an incredibly diverse selection of artists, disciplines and approaches whose work is loosely connected to themes around the magical and the occult, ritualism and alchemy. Among the artists showing are Brandon Anschultz, Harley Lafarrah Eaves, Hélène Delprat, Trenton Doyle Hancock and Charline von Heyl, Chris Burden, Farrokh Mahdavi and Marilyn Minter.

The work of these contemporary artists is presented alongside a series of Vodun fetish objects called “bocio”. These objects are created by the Fon people originating in Benin, Africa. The term Vodun is linked to the Fon religion regionally called Vodoun, Vodzu or Vodu, which refers to the polytheistic belief in “numerous immortal spirits and deities”. There’s a reason the gallery has chosen to show these objects over any other number of icons relating to mystical practices. From 1719 to 1731, the majority of the African people captured and brought over to be enslaved in Louisiana, a state not far from Missouri and with close ties to St Louis where the gallery is housed, were Fon people who brought their beliefs into the US (as far as they could, of course.)

Fon fetish objects, like the ones on show, are wooden figures made by blacksmiths under the order of a diviner, and are traditionally used by families for protection. Said to “embody the well-being of the village”, the objects are usually set on a peg and covered with substances believed to have magical properties, such as organic materials, bones and other animal parts, as well as accoutrements like string and padlocks, which are all believed to imbue the objects with unseen powers.

While there’s something a little uncomfortable about the connection to, and almost celebration of, the way such objects have found their way into the US, it’s interesting that they’ve been selected as a foil to works by the likes of Burden and Minter. The gallery bills the show as an exploration of art as a “tool for protection against the precarity of our lives”, and of “the impulse toward the magical and occult in response to catastrophic cultural circumstances”—which again, is a strange sentiment next to objects used for centuries in traditional African belief systems based on age-old lore rather than metaphor.

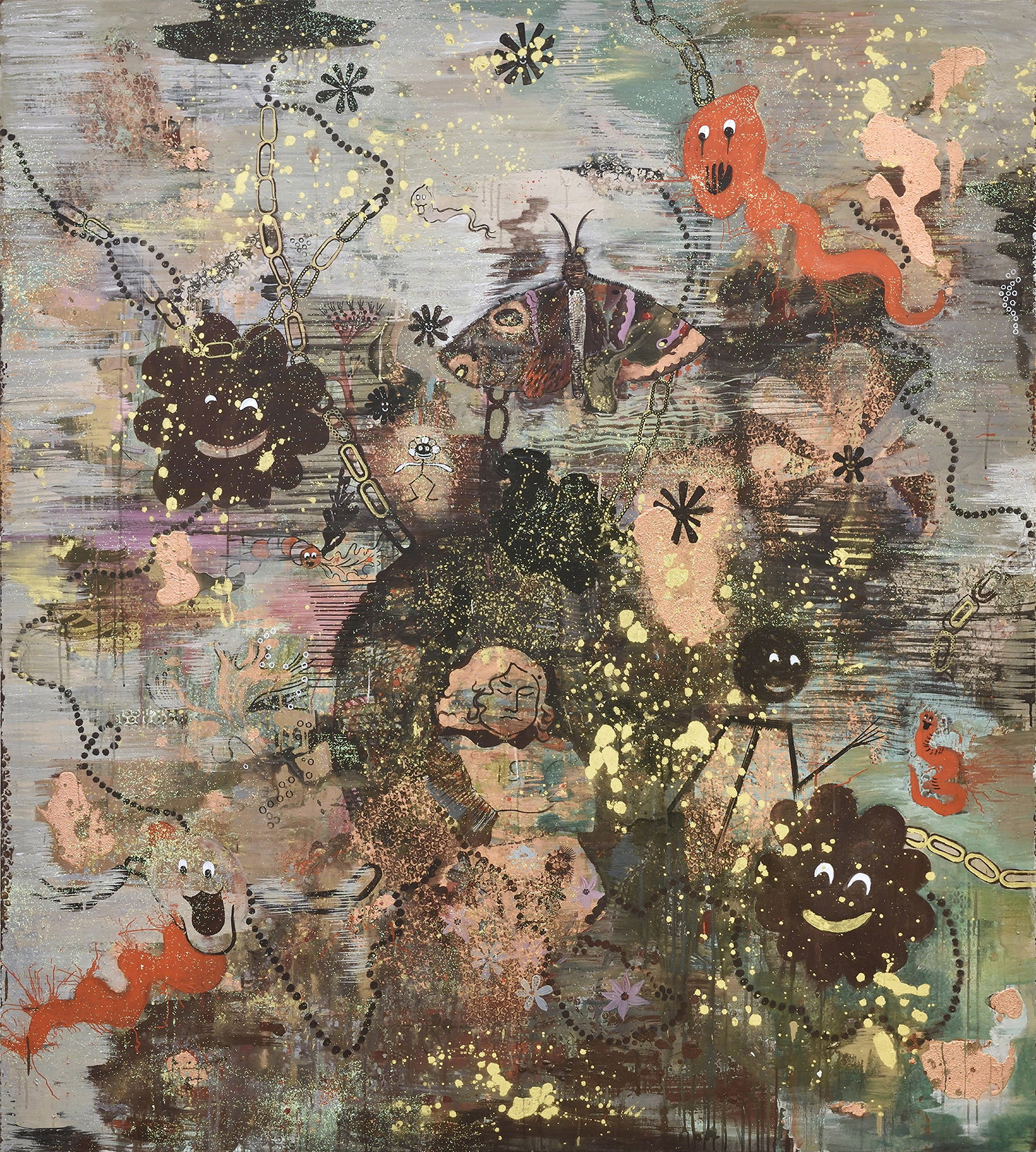

Among the contemporary pieces shown in the main gallery is Hélène Delprat’s Lost Sleeping Beauty (2018), which uses layers of abstract textures that bear semi-hidden images of phantasmagorical beings such as ghouls, anthropomorphized flowers and moths. A 2018 painting by Harley Lafarrah Eaves, titled Thematic Plot Points In the Wizard of Oz from Childhood Memories, takes familiar motifs from the film, such as Dorothy’s picnic basket and the creepily spidery fingers of the Wicked Witch, as well as her broom. These images, like those in Delprat’s work, look to create a sort of spell by recontextualising familiar images, often those associated with more childlike notions of the mystical, then deconstruct and reassemble them in an attempt to recreate that sense of wonderment and magic of childhood that becomes far bleaker as adults.

“As a new decade begins, we find ourselves skeptical of conventional means of asserting control over our circumstances”

The rear gallery of the space includes pieces that are connected to some of the many emotional plagues of contemporary life; such as anxiety, apprehension, isolation and alienation. Burden’s 1974 piece Untitled is an offset lithograph that focuses on sleeplessness; while James Hoff’s Social Media Remorse Syndrome from 2012 plays with the language of diagnostic criteria. The works by contemporary artists were selected because their pieces “either suggest, or actively engage in, mystical strategies as wishful protections against otherwise uncontrollable conditions”.

The gallery adds, “As a new decade begins, we find ourselves awash in anxious precarity—from the unstable fate of our political future to the critical state of the environment—leaving us skeptical of conventional means of asserting control over our circumstances. Therefore, alternative logics—ones that push against established, worldly orthodoxies—gain substantial appeal as viable methods for thwarting unwanted outcomes that have otherwise seemed immune to the precautions and solutions of standard rationale.”

All images courtesy of Projects+Gallery