On my first day at art college, I dressed for the occasion. High-waisted jeans, brothel creepers, sheer oversized shirt. I had long stood out at school, with flamboyant outfits that made my mother roll her eyes as I walked out the door. Although I would have been too embarrassed to admit it, I expected to make a similar impression amongst my new peers. But when I found myself surrounded by hundreds of others with similar aspirations, I realised just how easily I could fade into the background. In the end, I only spent a few months at the college before dropping out.

I still enjoy getting dressed up. I’m less eager for approval than I once was, but I can’t help momentarily returning to the vain aspirations of my 18-year-old self. Perhaps it’s hardly surprising; in the creative industry, self-presentation is intimately entwined with the making of an identity. The image of the creative individual is one that has consistently been capitalised upon and circulated by brands, from artists enlisted in fashion campaigns to designers invited to open their studios for “behind-the-scenes” content.

My sense of self was shaken on that first day of school, but I’ve faced far greater challenges to my identity since. Years after graduating (from another university), I found myself returning to retail jobs that I had hoped to leave behind in my teenage years. I began to see myself as the customers in the store saw me: invisible beyond my basic role. I felt like I was slowly eroding, and stopped reading on my lunch breaks. Instead, I sat and numbly scrolled through my phone. I obsessed over others who I deemed more successful, more fulfilled and more productive. At times, I imagined that I didn’t exist.

“In the creative industry, self-presentation is intimately entwined with the making of an identity”

Of course, it was my own aspirations that were making me unhappy. I made friends with lots of people who had built successful careers in retail and hospitality, yet I saw myself as somehow different, and wanted the world to sit up and take note. My frustrations stemmed from my own expectations of who I was, and who I ought to be. I clung onto my identity as a creative person as if it was the only aspect of myself that mattered.

During lockdown, many have grappled with the difficult challenge of reshaping their creative aspirations, too. When considering the prospect of enforced isolation, it wasn’t uncommon for artists, musicians and designers to relish the opportunity for some much-needed creative focus. Finally, those side-projects that had been left to languish would come to completion. In reality, many found themselves unable to tackle even simple tasks when faced not only with the shock of the pandemic but the boundaries of their own ambition.

In a recent article for The Cut, titled “I Miss Having Ideas”, Katie Heaney mourned her own loss of creativity post-lockdown. “I’ve managed to maintain a regular output of stories here at my job. But I have not felt inspired, or creative. I’ve just been trying to get by. On humanity’s list of most pressing concerns, ‘I have no ideas’ ranks pretty low,” she admits. “But it is demoralizing, and depressing, to lose something that once consistently brought you joy and pride.” She mentions countless others who share her predicament. The anxiety that comes with that perceived sense of personal failure, of letting yourself down, is rooted in the loaded expectation that you should be able to consistently produce more.

The inability to express yourself creatively doesn’t always stem from within. The culture industry, already a narrow and precarious field, has continued to shrink in the wake of the pandemic. Many of those facing redundancy will have to consider alternative roles or careers. I know freelance writers who have already made the shift to marketing or consultancy, and photographers who have taken on commercial jobs that they would have turned down prior to lockdown. After defining themselves by their creative output for so long, they are now faced with the existential question of who they really are, and who they might become.

“When price is so often used as a measure of worth, it’s easy to feel like your creative side barely exists”

The question of success and failure is central to any discussion of ambition, but the parameters by which we measure these two extremes have shifted over time. The possible routes to a role in the creative sector have shrunk, while the myth of a meritocracy looms ever larger. Jobs in the industry now typically require at least one university degree, while apprenticeships and other forms of specialised labour have all but disappeared, along with the polytechnics that once provided the backbone of British education. Meanwhile, the financial burden of tuition fees has left millions burdened with debt that they have little hope of repaying, with art school providing no guarantee of stable work upon graduation.

To make matters worse, the industry has become even more crowded in the age of the internet. In an article for the New Yorker last week, Hua Hsu detailed how creativity has been devalued in the digital age. “The Internet was supposed to free the artist, and to democratize and de-professionalize the practice of art,” he writes. “In some measure, it did—while also demonetizing art itself.” Increasingly, creativity is a hobby and not a job. But when price is so often used as a measure of worth, it’s easy to feel like your creative side barely exists.

The pursuit of success in the industry can feel like a treadmill that never stops, with many pushing themselves to overwork. In a relentless attention economy, the desire to stand out is more powerful than ever. During uncertain and turbulent times, it is important to remember the value that lies beyond creative achievements.

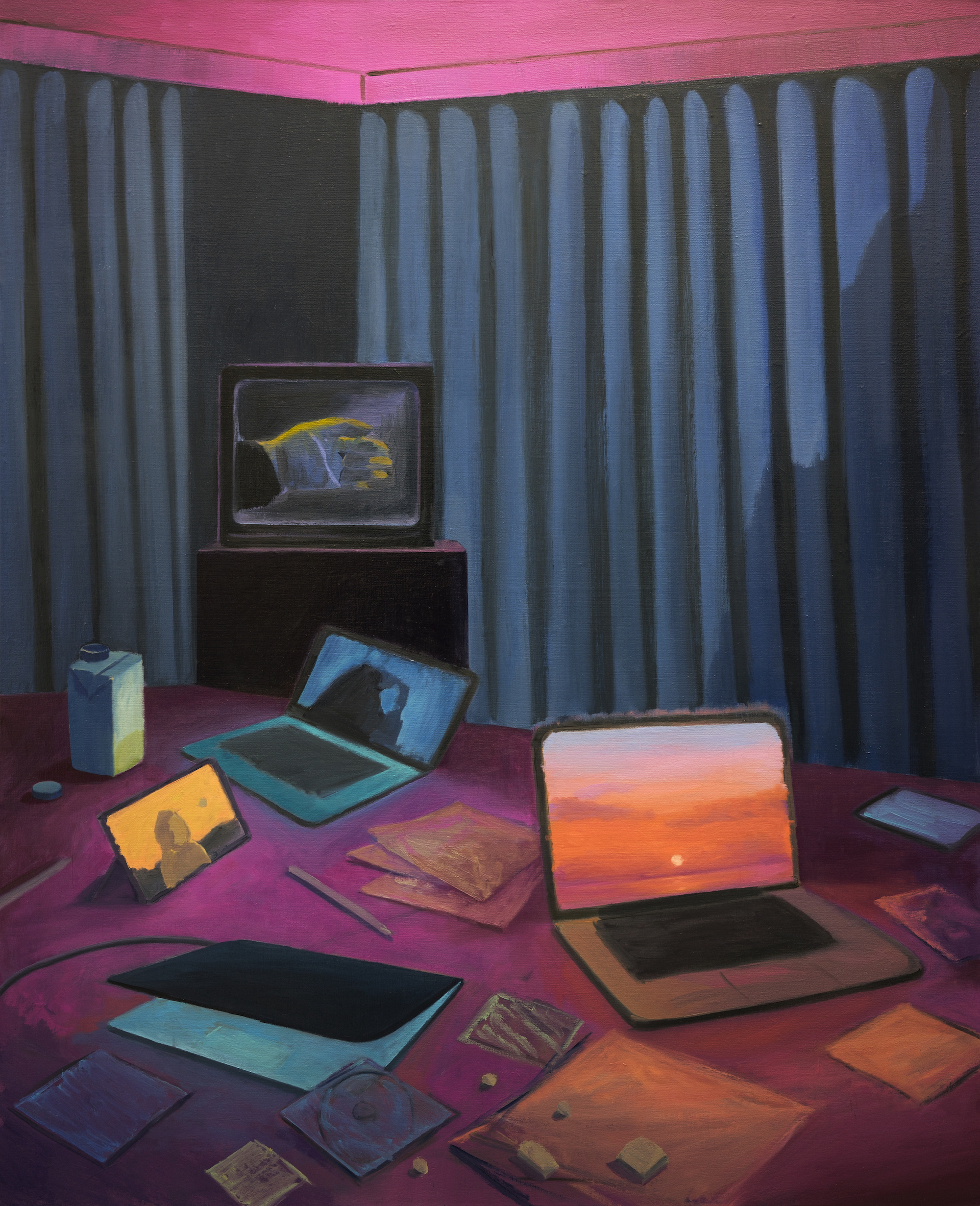

Are We There Yet is a fortnightly column by Louise Benson. Top image © Minyoung Choi