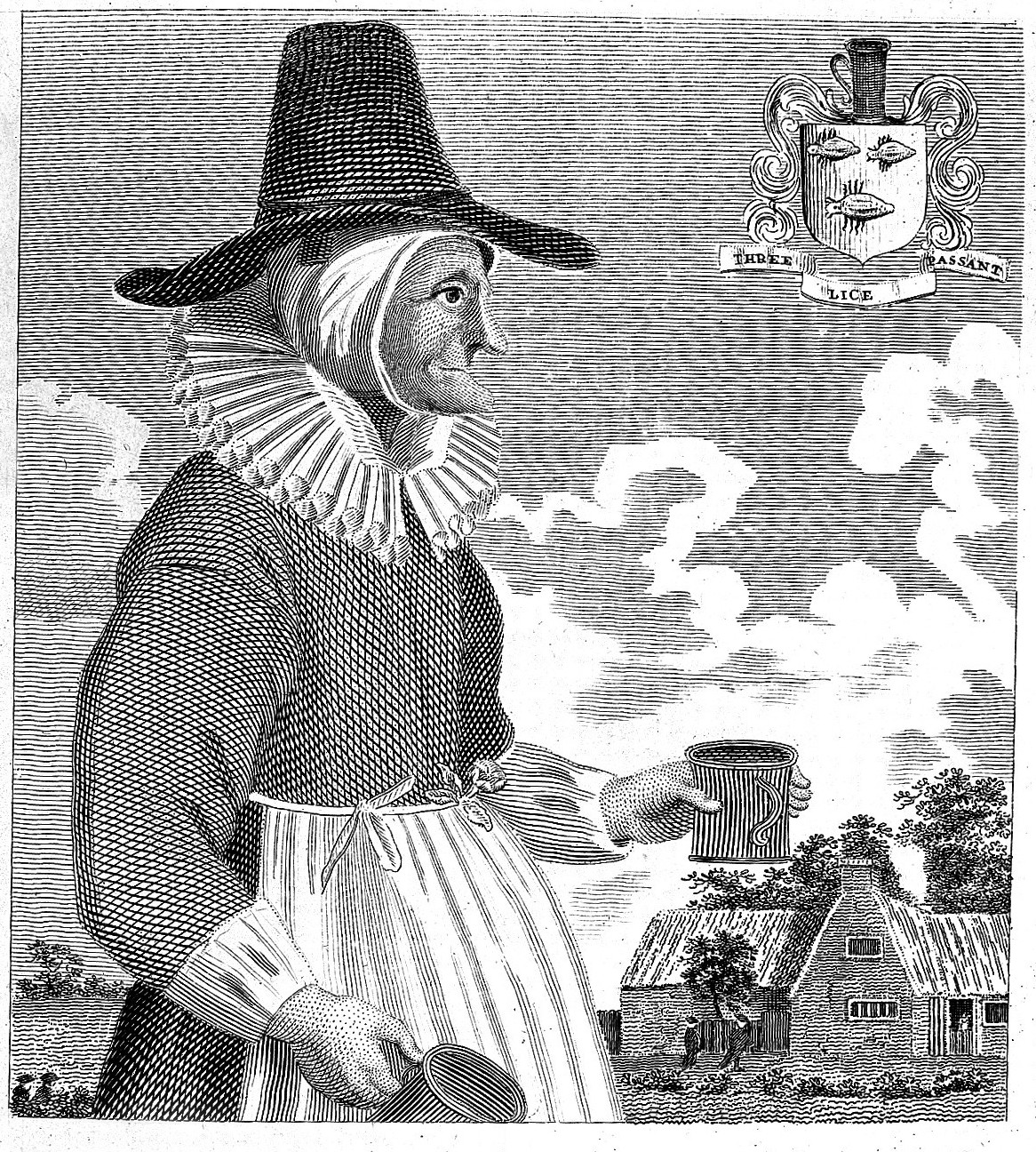

What do you see when you imagine a witch? For most of us, the word is synonymous with an old woman sporting a tall pointed hat and accompanied by a familiar feline, a bubbling cauldron and a magical broomstick. It is an image so ubiquitous that few of us consider where it originated, but it comes as no surprise to discover that it stems from propaganda designed to discredit entrepreneurial women in a patriarchal society.

According to Heather Hogan, a beer expert who features on the Hell Mouth-orientated podcast Buffering the Vampire Slayer and writes on the forgotten history of beer’s female-dominated origins, this powerful contemporary motif stems from the persecution of “alewives” by the medieval church.

“The notion of a witch, formerly a symbol of pagan ritual and spirituality, became synonymous with the persecuted brewers”

The title describes self-sufficient female brewers who became prevalent following the Black Death—as people died families collapsed and women had to fill traditionally male roles—but were soon seen as scourges of society by the establishment because they earned their own money, wielded power and had no need to marry. As Hogan explains:

“Here’s what an alewife looked like: She did her brewing in a giant cauldron; boiling water, adding grain, overseeing the fermentation process. To keep the mice away from her stores of grain, she kept plenty of cats around. When she had extra beer to sell, she put a broom out in front of her house to signal the surplus. Or, she went to the market, where she took the fashion of the day—the henin, a tall white steeple-shaped hat—and made it black, to stand out in the crowd.”

Soon, sermons were delivered condemning these women as immoral and duplicitous, images of their “sinful” activities decorated church walls and The Chester Plays (one of the most popular morality theatrics of the mid-1500s) sealed the alewife’s fate as the most hell-bound occupation on the planet. The notion of a witch, formerly a symbol of pagan ritual and spirituality, became synonymous with the persecuted brewers, and thus the image of the satanic hag was born.

“The relationship between witchcraft, female autonomy and sisterhood is far more than a Western-centric caricature”

Nowadays, a basic bitch (basic witch?) Halloween costume will probably involve a black minidress with the aforementioned hat, in an allusion to the double-headed stereotype of demonic, vengeful crone and treacherous seductress. But the relationship between witchcraft, female autonomy and sisterhood is far more than a Western-centric caricature. In recent years the reclamation of occult heritage has become part a wider cultural phenomenon that encompasses intersectional feminism and LGBTQ activism.

Take musician Princess Nokia, whose allusions to her bruja heritage are inextricably linked to resistance of the white dominance and the patriarchy, or Bri Luna, otherwise known as The Hoodwitch, who offers a whole host of folk medicine, literature and spiritual advice relating to “everyday magic for the modern mystic”, all of which is informed by the witchcraft practiced by her grandmothers. Artist, activist and curandera Fannie Sosa explains the significance of “the open-source shaman or witch” as a counter the priests who have “monopolized the channels to address God and promoted the sublimation of the sexual vital impulses as the basis of a holy body/mind”. Her practice is rooted in reconnecting sexuality and spirituality through restorative ritual forms.

A recent swathe of UK exhibitions has also examined the relationship between witchcraft and collaborative feminism. At the Ashmolean Museum’s Spellbound, historic objects and archival accounts of sorcery (including Helen Duncan, the last person to be imprisoned under the British Witchcraft Act of 1735) are shown alongside new contemporary commissions such as Katharine Dowson’s Concealed Shield, an installation that evokes mysterious forces that surround the viewer and appear to pierce “a witch’s heart”.

Likewise Hummadruz, who was recently on show at Newlyn Art Gallery in Cornwall, brought together artefacts from The Museum of Witchcraft and Magic, twentieth-century works by the likes of surrealist and occultist Ithell Colquhoun, and contemporary interventions by modern-day counterparts including Jill Smith and Linda Stupart. The latter disseminated instructions for her “free spells to use at home” including A Spell to Bind Male Artists from Murdering You (in Tribute to Ana Mendieta) and A Spell to Prevent a Spell to Bind Straight White Cis Male Artists from Getting Rich Off of Appropriating Queer Aesthetics and Feminine Abjection. They are all available to download via her website.

- Spells © Linda Stupart

Stupart’s enchantments are also exhibited at Nottingham Contemporary’s Still I Rise, an exhibition about the multiple histories of feminist and queer art practice that includes a gallery devoted to the theme of “Spell”. This section aims to “look at the way that artists draw from ancient practices of ritual and witchcraft” to find alternatives to traditional patriarchal power structures.

Here, Xenobia Bailey presents Mothership 1: Sistah Paradise’s Great Wall of Fire Revival Tent, a large-scale crocheted shelter that offers sanctuary and connection to the legacy of Obeah healing practices. Likewise, Osías Yanov commemorates the struggles of trans activist Diana Sacayán and grassroots feminist movement Ni Una Menos in his queer talisman AOOT, while Jala Wahid’s ferocious sculpture Final Blade investigates “the idea of a weaponized female body, which sits at the threshold of the seductive and the abject”.

This piece protrudes from the wall up on high, appearing like a giant claw or sliver of human bone. In this way, the artist encapsulates both the awe and terror that is traditionally associated with witchcraft without envoking stereotypical imagery. It feels inherently violent in a way that sets it apart from other works that are predominantly associated with themes of preservation and protection. In this way, it serves as an important reminder of the marginialization and persecution so many people have faced at the hands of the term “witch”, and the reclamation that so many now seek.