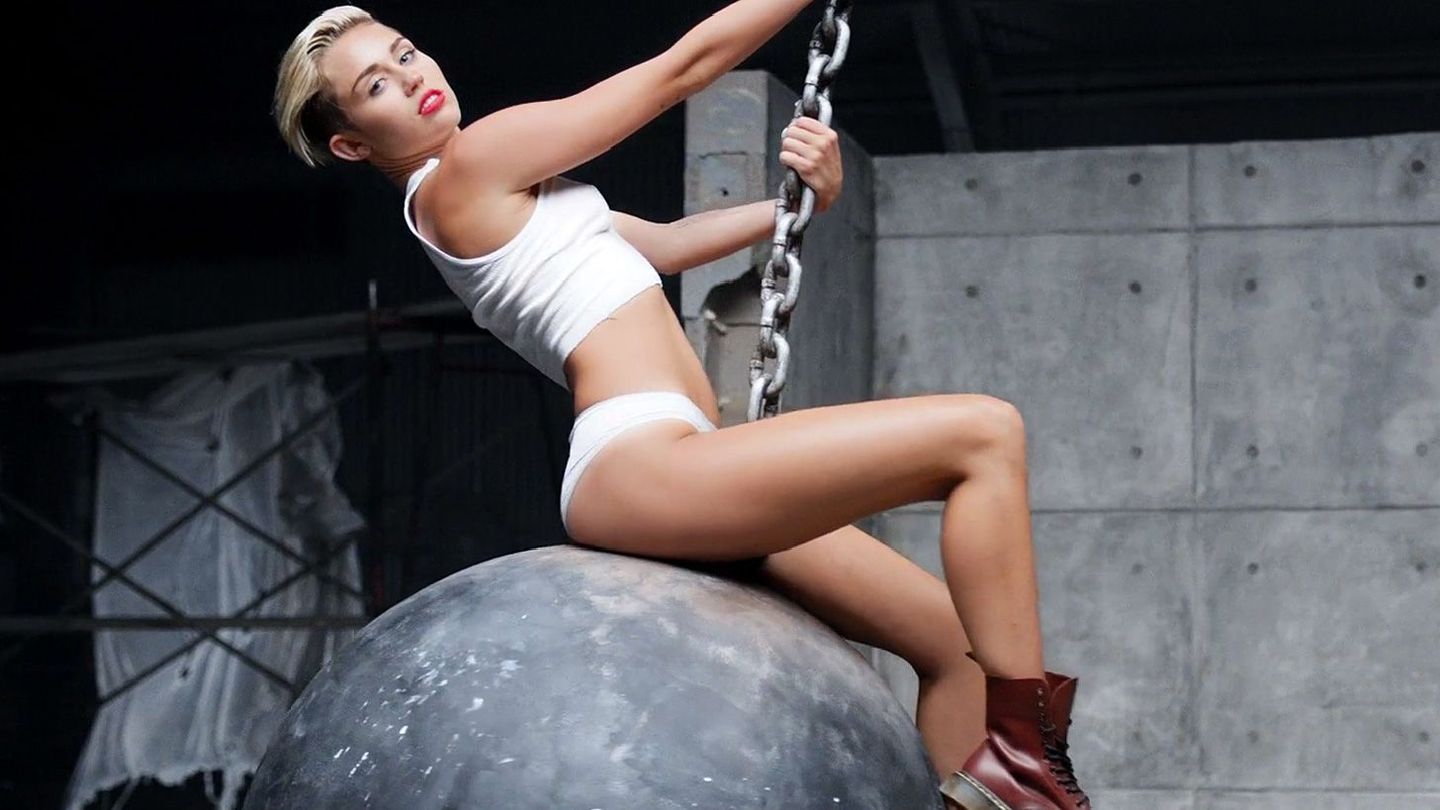

Sexual intercourse began in 2013 (which was rather late for me), somewhere between the video for Wrecking Ball by Miley Cyrus, and the 2013 VMAs on MTV. If many of us, at some point between the ages of sixteen and twenty-three, had mistakenly believed we had been singlehandedly responsible for the discovery and embodiment of sex, none had been given quite so dizzying a platform for espousing this belief as Miley Cyrus, who began her career as a Disney kid and then decided, at the age of twenty-one, to rebrand as a shaven-headed, permastoned and half-nude latex babe. Aside from stripping off, her signature became a long, extended tongue, a move that placed her halfway between puckishness and fuckability; her platinum crop, blonde like a star but confrontational like a skinhead, flummoxed those who had mistaken her attempt to appear wildly sexual for the pursuit of quotidian sexiness.

She took up twerking, somewhat clumsily, beginning an inelegant period of “borrowing” from black culture whenever it suited her, then disavowing it with just as little care. She began showing a tentative interest in the world of kink, slipping on bondage-wear for the hip, Quentin-Jones-directed introductory video for her Bangerz tour, and sat rodeo-style on an enormous hot dog to perform, winking in case anyone out there had been slow to get the joke. “I’m very confident being naked,” she informed The Daily Mail, as if this were somehow surprising for a skinny, pretty white girl with a personal trainer and a very famous Daddy. Doubtless, everybody joked, Billy Ray’s heart had never been achier or breakier than it was in that moment, watching Miley share her sexual awakening with everybody in America who owned a television.

“It is an unnervingly perfect mirroring of the erotic inner life of someone barely old enough to drink legally in a bar”

“Were it not for David Lynch,” Billy Ray Cyrus had told GQ, cryptically, in 2011, “Miley would never have been Hannah Montana… [and that show] destroyed my family.” What he meant was that because he had received his first screen credit in the auteur’s 2001 Mulholland Drive, Lynch had provided a way for the family to enter into Hollywood, and so for Miley to aspire to being on the Disney Channel. It may have escaped Billy Ray Cyrus’ attention that Mulholland Drive is not only a film about the fate of women in the movies, but a cautionary tale: it hardly recommends a career as an actor or an actress. Had Lynch been available to direct Cyrus Jnr’s putative coming-out as an adult sexual woman, the resulting footage might have erred a little closer to the picture painted by the modern Miley, who has since disclosed a family history of mental illness and addiction, and who right now looks and sounds more like Wendy O Williams than a child star or a teenybopper.

Sadly, the director on-hand to record her transformation was the fashion photographer Terry Richardson, best-known between 2004 and 2010 as an equal-opportunity documentarian of celebrities, haute-couture and erect dicks, and best-known now as an alleged serial harasser of his models. His music video for her single Wrecking Ball, a masterpiece of obviousness and boring sexual innuendo, is a fascinating object for the worst possible reason: despite having been made by an almost-fifty-year-old man, it is an unnervingly perfect mirroring of the erotic inner life of someone barely old enough to drink legally in a bar.

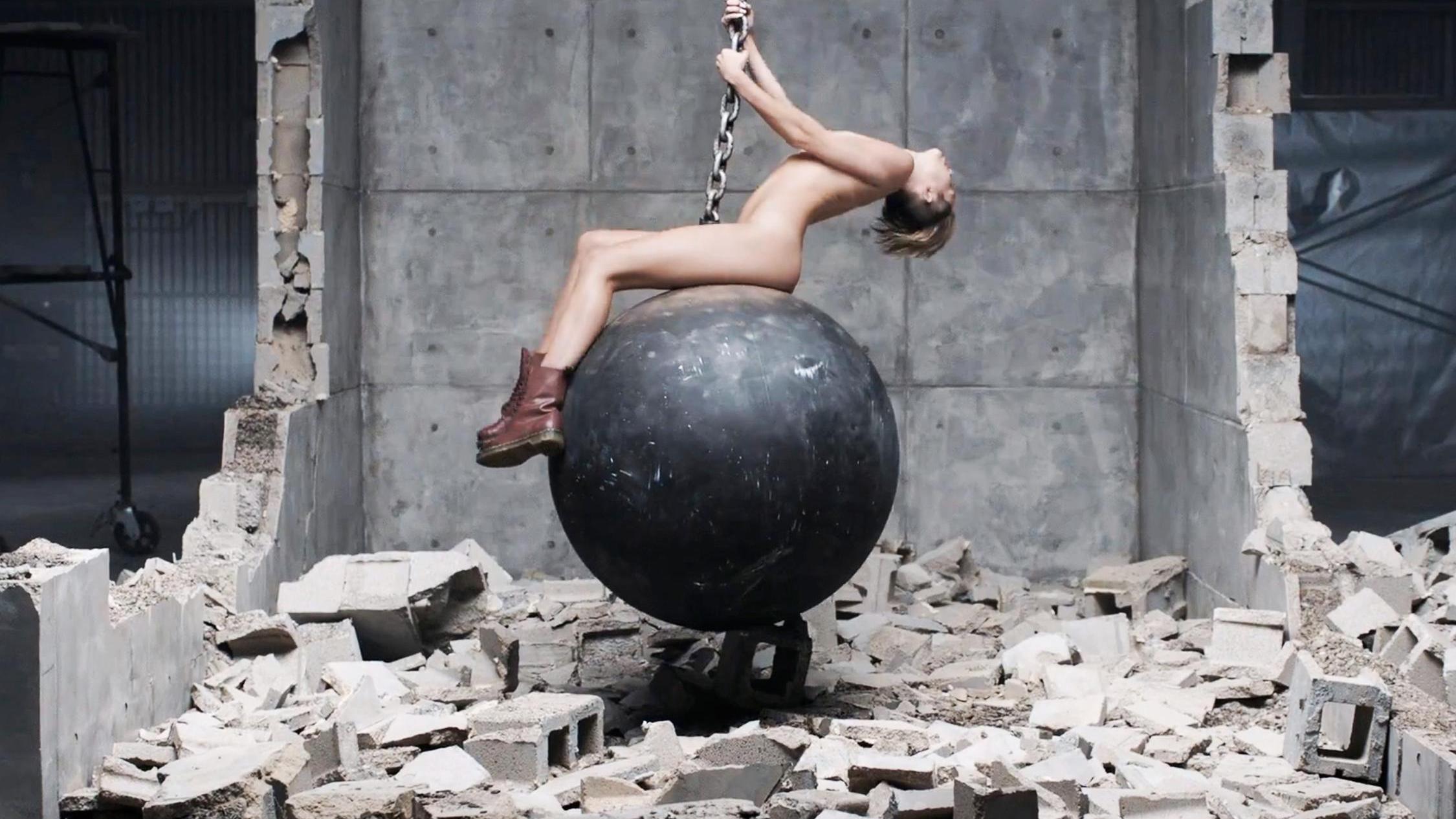

In the clip, Miley cries sweetly into camera, licks a sledgehammer—c’est ne pas un sledgehammer, obviously, c’est un pénis—and swings nude while seated on a wrecking ball; she wears a white vest and pair of white men’s underpants to writhe around on shattered concrete, representing the broken-up wreckage of her failed relationship, a metaphor that would not seem entirely out of place in the term-paper of a teenager. Incessantly, she bites her lip, the gesture curiously laboured as if learned from browsing the Victoria’s Secret catalogue for inspiration. “If you look at my eyes, I look more sad than actually my voice sounds on the record,” Cyrus said in a radio interview. “It was a lot harder to do the video than it was to record the song. It was much more of an emotional experience.” It’s true that Miley, in tight close-up, does look mournful, her blue eyes brimming convincingly with tears; it’s also true that the video’s dumb insistence on her sadness being made sexy, as if we might not have listened to her if we could not also see her tits, undermines its emotional power.

Miley Cyrus in Wrecking Ball, directed by Terry Richardson, 2013

One can hardly blame a twenty-one-year old who had spent her formative years being a squeaky-clean, immaculate performing monkey for the Mouse for wanting to rework herself into a dazzling mega-harlot, nor for believing she might have been the first to have the idea. “Each generation thinks it invented sex,” the sci-fi novelist Robert A. Heinlein

famously suggested in 1980, twelve years before Miley’s birth. With Wrecking Ball, Richardson failed to invent anything at all, any controversy immediately following its release dying down into radio silence.

“The video’s dumb insistence on her sadness being made sexy undermines its emotional power”

Allegations that had dogged the photographer since the very earliest years of his career eventually coalesced into a ban at Condé Nast, the equivalent of a professional death sentence for a practitioner like Richardson, whose work with brands and celebrities had conferred legitimacy on what might have otherwise been a career producing stylish hipster porn. (“It confuses me why so many seemingly intelligent, right-thinking people—Louis C.K., even!—put up with him,” a Flavorwire blogger had exclaimed in 2013

, proving that modern life is and has always been a very long skit by Chris Morris.)

Wrecking Ball remains as an intriguing testament to blatancy: self-explanatory visual gags and sexual subtext rendered text, the obviousness of Richardson’s consistent sleaze. “[The song] Wrecking Ball—I’ll do it, but I don’t love it,” Miley groaned this year, sounding like every other 27-year-old thinking about something unsophisticated and embarrassing they did at 21. “I’ll never live down when I licked a sledgehammer.”

Elephant’s Contemporary Classics series spotlights iconic moments in visual culture from the last two decades.