From his photographs of the dirty floors of Tokyo nightclubs to his infrared images of other people’s houses at night, Yamatani’s work vibrates with a rebellious energy. He has exhibited in group and solo shows in Japan, China, the US and Europe, and will be on show in Yuka Tsuruno Gallery’s booth at Photo London.

How did you begin taking photographs?

I have played drums since my teenage years. At twenty-two I was tired of creating things with others and longed to express myself in a way that could be done alone. My girlfriend at that time was older than me. Her ex-boyfriend and the one before were both photographers. When she told me about it, I became curious about what a photographer was, and she kept encouraging me when I casually took photos with the camera she had. Then I became engaged with it. I began thinking I needed to become the best photographer out of all her boyfriends, so I bought a camera. Difficult techniques are not required when using a camera and you can have a comfortable distance from your subjects, and record your days through photography. All those aspects match with my personality, so I became absorbed in taking photographs. I broke up with that girlfriend two years later, but I think of her from time to time and each time I thank her.

You have spent a lot of time photographing subcultures, including the underground scene in Osaka. What is your relationship to these groups?

I like the uniqueness and size of Osaka as a city, and I wanted to record things that were happening in my everyday life. Music was my biggest passion before I started photography and it has a strong influence on my day-to-day life. I wanted to go back to the venues where I used to play every week, but this time with a camera. I contacted a guy from my old band and we shared his room in Osaka. It was my first time actually living in Osaka but I made a lot of friends. We were out every night.

There is a real sense of rhythm and movement in your photographs—has making music influenced the way you make images?

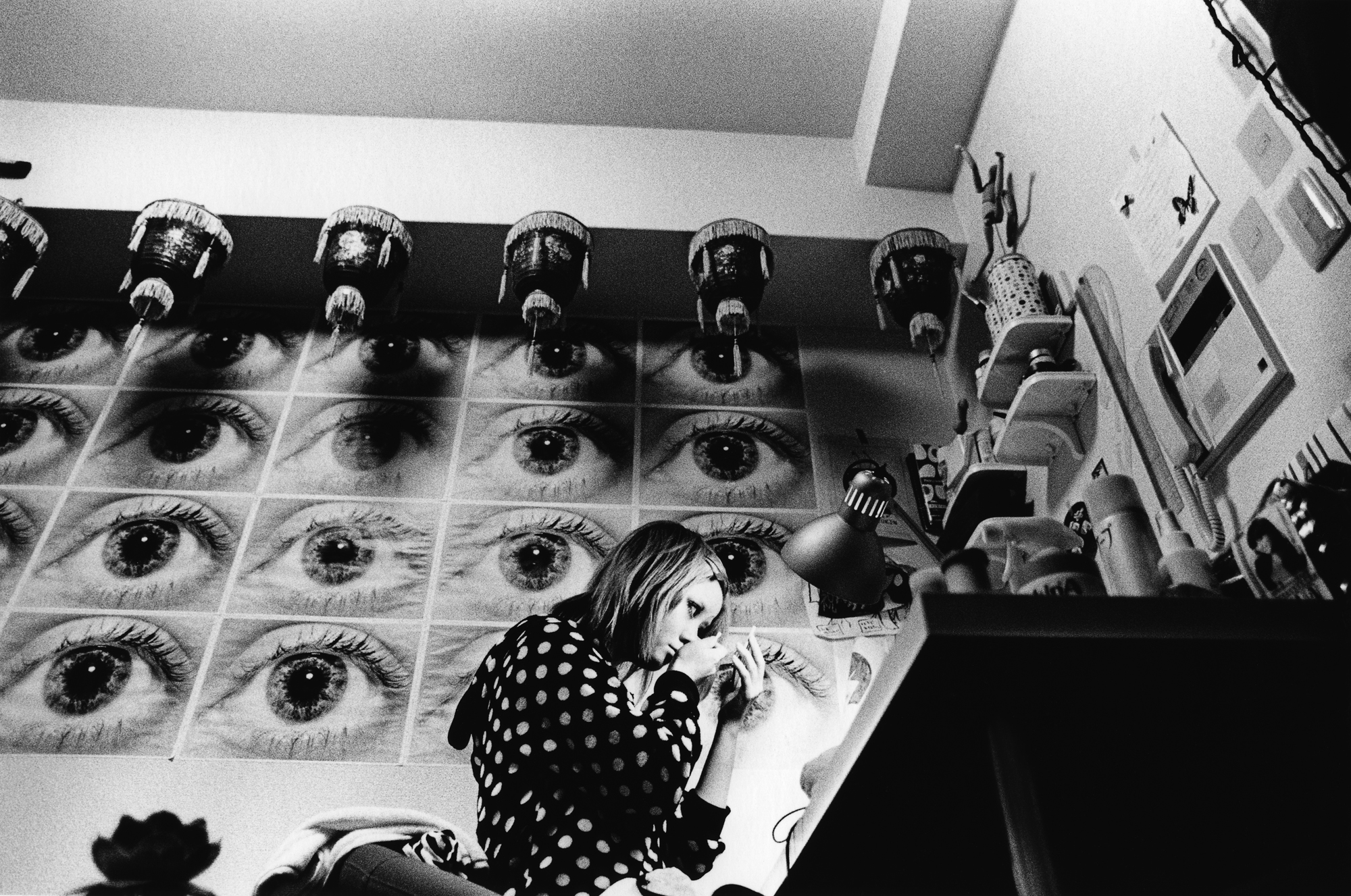

Music was my everything when I was a teenager. My whole life was steeped in music culture. My thought, fashion, and everything I did was deeply affected by it. I keep changing and have now become tolerant of many things, but I still keep the core—that has not changed since I was a teenager. Many of my friends are the same. I like the naturalness when people perform music: their natural gestures and attitude, and the atmosphere that comes with that. These things exist in street scenes and simple moments too. Photography is the most appropriate expression to outline personal experience and also to let others sympathize. In my photographic work there are no pictures of live shows or skateboarders tricking. I am not interested in photography where the subject is playing up to the camera. I think that the magnetism of photography is to be able to frame the naturally overflowing experience [of everyday life].

Also, it may be related to the musical instruments I have been playing for a long time, like drums. I always care about rhythm when making photographs. In particular, photo albums that show work in a stream. This is a medium that can accurately convey the intention of a work, accompanied by rhythm.

Your series Into The Light uses an infrared camera. What was the idea behind this series, and how did you find working with infrared film as opposed to black and white?

I got married in 2014 and published photographs of my honeymoon in Japan in a book titled Rama Lama Ding Dong. Then I had a child in October 2015. It was a spectacular experience, but when I became a father I was, at the same time, puzzled by this situation that I had never before experienced. Sometimes I left my child to cry at night and left my wife to take a walk to get away from home. And while walking around the residential area in the evening, I became interested in other people’s houses, and started shooting this series of infrared photographs. My interest in the houses of other people has led to the desire to “look into the home”. That idea led me to the infrared camera. Even with an infrared camera that responds to invisible rays, we cannot, of course, take a peek into these houses. The desire to have a glimpse of human activities, despite its impossibility, made me strongly aware of “seeing” and “being seen”. I thought that I could express the relationship we have with other people in modern internet society. Technically, the current infrared film was unable to shoot what I wanted, so I had a trial and error period which led me to remodelling a digital camera. When I faced a house in the middle of the night, what I felt was fear. It was because I felt that I was being seen by the subject that I was looking at. To convey that disturbing ambience, the unique colour of infrared worked very effectively.

I’ve read that you were taught by famed photographer Shomei Tomatsu, who you were introduced to in Nagasaki. What other photographers or artists have been influential to you?

There are many amazing artists have been influential to me. As I would not be able to say one in particular, these are some of my favourite photo books: Bruce Davidson’s Brooklyn Gang, Dash Snow’s Polaroids, Jacob Holdt’s American Pictures, Diane Arbus’s Aperture Monograph, Wolfgang Tillmans’s Lighter, Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel’s Evidence, John Divola’s Three Acts, Todd Hido’s House Hunting, Daido Moriyama’s Hunter and Takuma Nakahira’s Circulation: Date, Place, Events.