Writer Will Jennings reviews Hannah Perry’s current exhibition ‘Manual Labour’ at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art after speaking with her, exploring the artist’s themes of gender, motherhood, and industrial (or non-industrial) labour.

When Rank Hovis opened the Baltic Flour Mill in 1950, it held 300 workers managing over 22,000 tonnes of grain in a towering deco building on the Gateshead side of the River Tyne. Men worked with the most modern factory machinery of the day as they produced and distributed flour, while women were employed in the cafeteria and offices. With a vast open interior, it was a hive of activity with deafening mechanical noises ricocheting around an open interior, and lorries and boats continuously brought in grain and took away flour.

Now, over four decades since its closure and 22 years since it reopened as the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, some of that industrial energy is back inside. Artist Hannah Perry has constructed a series of scaffolding rigs and industrial structures to take up the space of the Baltic’s largest double-height gallery. It isn’t just the physicality of Perry’s work that fills the space, however. A 14-channel soundtrack fills the air in an overlapping, glitching, and occasionally mechanical noise. It is the score to Manual Labour, an HD video projected onto the screen of the largest piece of the installation-triptych, and the centrepiece of Perry’s triptych of installations.

“It’s overwhelming. Purposely,” the artist says of works, which are the largest she has made across her career since graduating first from Goldsmiths and then the Royal Academy Schools. “I came up in 2019 for a site visit and just straightaway I was really intimidated by the space,” Perry recalls, “the scale was a bit of a step change for me – I’ve probably worked in a space half the size, at a push, maybe in Graz.” For the Graz show, Rage Fluids at the Künstlerhaus in 2018, Perry filled the gallery space with an undulating, sinuous metallic surface stretched over a framework, compressing the distorted reflection of the viewer into the work itself as bass from speakers sends ripples across its surface. That exhibition was rooted around the subject of masculinity, as much of Perry’s previous practice has been, with her metal-worker father involved in production of the metallic surface and structure.

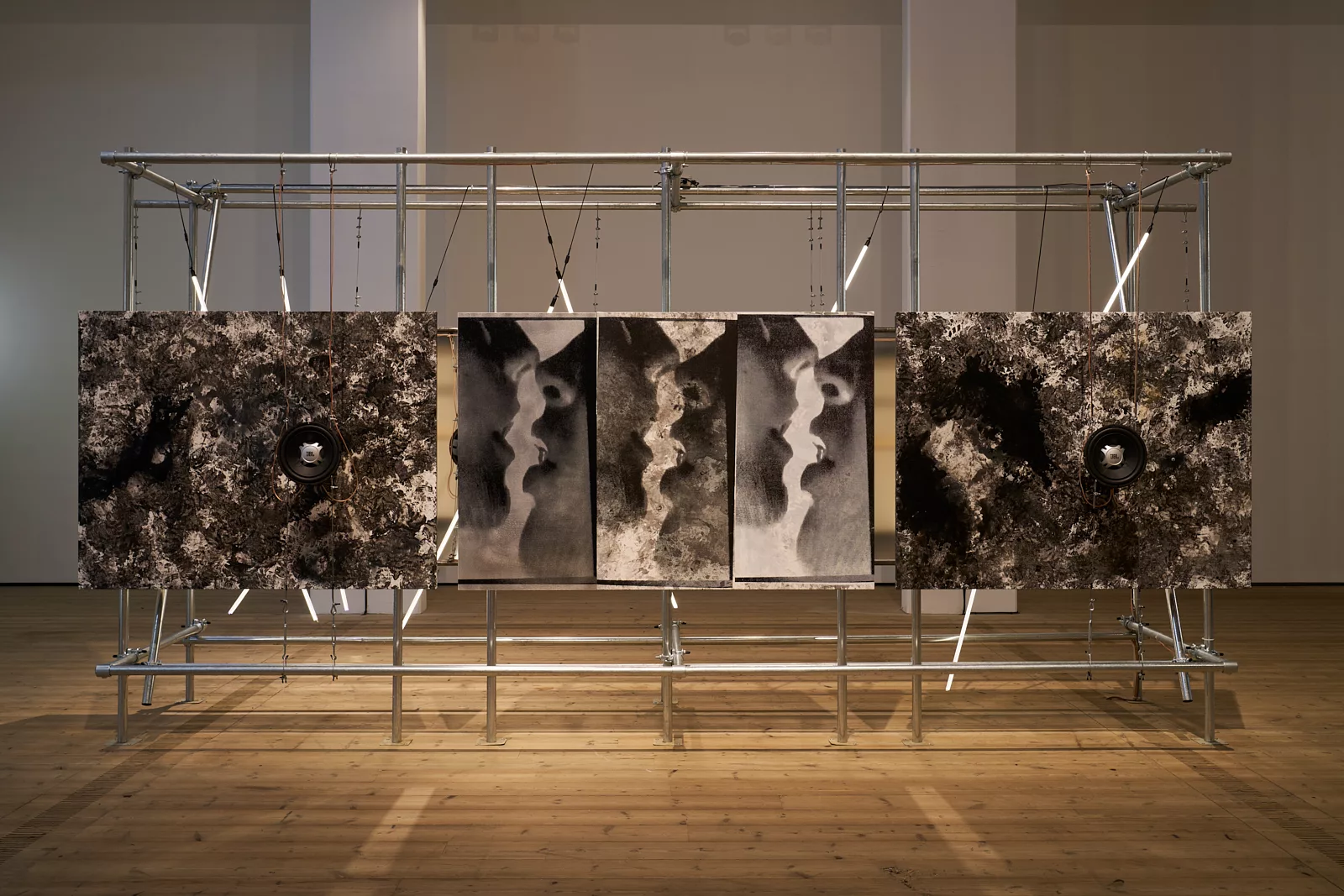

There is a similar steel framework in the Baltic, with four subwoofers forcing bass against a taut car body wrap surface. This whole project was intended to become an exhibition continuing that exploration of masculinity, considering her dad’s history of work in industrial fabrication and her brother’s experiences in the mining sector. Indeed, it was a body of work that grew from a 2019 artist-in-residence programme at the Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art, Russia.

There, Perry filmed the largest titanium factory in the world, just outside Siberia, and immense asbestos mines at Asbost, Sverdlovsk Oblast, with a drone. She notes, “They excavate the stone with explosions, and I wasn’t that keen on being there for that…” Originally intended to open in 2020, the Baltic show was to use this footage for a project looking at the male gender in both industrial processes as well as recreational spaces including physical fitness and ultimate fighting gyms. But since then, Perry says, “everything changed … everything completely changed.”

A lot has happened in the world since 2020. Putin invaded Ukraine and the Ural Industrial Biennial appears to have stopped, then Covid paused most of the world, and in the UK cuts to arts funding alongside increasing material, energy, and Brexit-related price-rises have resulted in huge issues for the cultural ecosystem. Amongst all of this—and because of some of it—the Baltic exhibition was twice postponed, and Perry’s personal world also changed a bit: the artist now has two children.

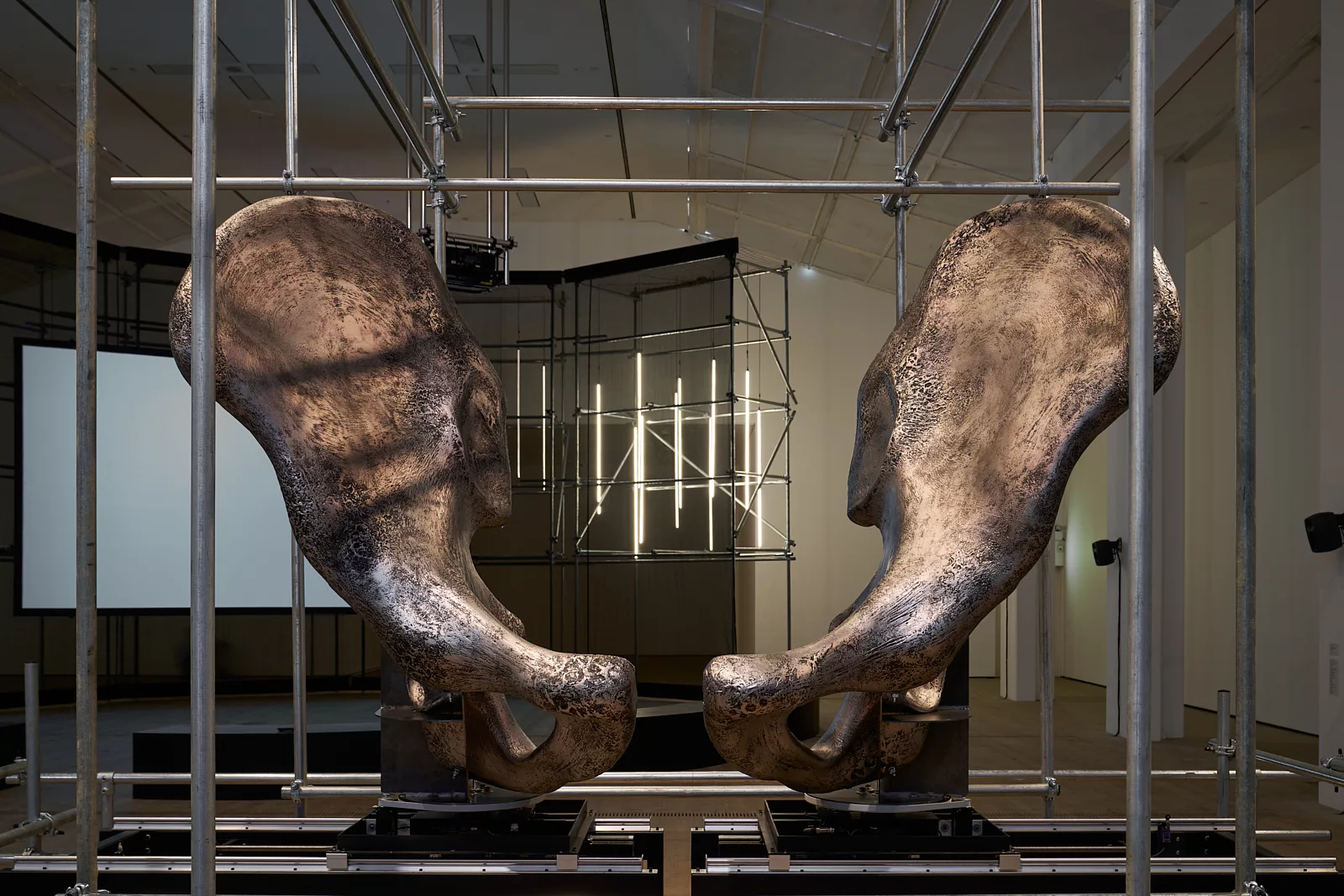

Gender is still central to the reconfigured exhibition, Manual Labour, but the core focus has switched its gender. What began as a look at male-centred work now focuses upon the female. The HD film still includes the metal and mine, but it’s intermingled with footage of Perry and her children—one in her arms, one still in the womb—standing within a mirrored space. On the other side of the framework with the reflective car body wrap are a series of screen prints and paintings, while the third part of the triptych is an enormous pair of pelvic bones, opening, closing, and gyrating mechanically. Included in the sound work reverberating around the former mill is audio from the birth of her son—Perry is now resolutely considering her own experiences and gender through the reimagined work.

“The idea of distribution of labour, particularly in the domestic space, is something that I’ve struggled with,” Perry says. “It’s not like all of a sudden that you’re not the same person as before, or you changed your priorities,” Perry observed, adding that “you still want your own autonomy, identity, sexuality, everything … it’s just that the infrastructure is just not there to support it.” Perry is picking up a theme of motherhood in the arts currently widely discussed— including by Hettie Judah in Elephant—around the lack of maternity leave as an arts freelancer, having to use personal money to survive, maybe taking your child to work (even though most non-art employers would not count it as an option), and undervaluing the value of domestic care and work which has no monetary reward and can impact a career.

With a practice rooted in research and writing, Perry has considered her own experiences with nuance. “I feel that I maybe had an internalised misogyny for an idea of motherhood … for me, it isn’t this kind of wonderful thing that was gonna make me complete, this is not what it is to me—I feel it is something that should add to an already full life.”

With the Covid and pregnancy delays, Perry packed up her Somerset House studio and took time away from the urgency of making art. But a creative mind doesn’t simply stop, and as well as writing constant notes and ideas Perry enrolled on a philosophy and psychotherapy course at a London college founded by R.D. Laing in the 1960s—or in the artist’s words, “a bit of a hippy-dippy, slightly alternative place.”

“It was just to get my brain reignited again,” Perry said, but her philosophical reading and research around how working-class women and mothers were viewed directly fed into ideas for this delayed Baltic exhibition: “In the film I talk about a Madonna-whore complex, which in psychoanalysis is Freud’s idea where men see women as either virtuous mothers or debased.” In the film, as well as the artist and her children, another lady intermittently occupies the mirrored-space construction, a pole dancer contorting at all angles.

The metal dancing pole in the film mirrors the metal structures around Baltic’s gallery, with the body gyrating around it poetically resonating with the mechanical pelvis sculpture, Antagonist. The movement of the two hip bones is smoother and fluid, but the mechanical operation is loud, visible, and industrial—not unlike the brute force of melting and shaping metal captured from Russia and cutting into the film. Where Perry’s original project focussed on the male body’s physical fitness and endurance in both work and leisure spaces, this sculpture speaks to female bodily exertion.

“The sheer physical trauma of birth is sort of talked about as wonderful and magical,” Perry says, adding “I mean, it is, but it’s also quite grotesque and gruesome, and actually super violent.” Like the pole dancer, the pelvic bones are playfully spinning, but there are other forces at play beyond the balletic. Antagonist is inspired by the hormone relaxing, produced by the ovaries and placenta to loosen muscles, joints, and ligaments during pregnancy. Perry explains: “When the baby’s born, if the pelvis is not big enough, the bones can dislocate and relocate … which is incredibly fucked up, and terrifying actually.”

The last few years have been quite a journey for Perry. Not only having to traverse Covid as a precarious freelancer but also bringing two new lives into the world and allowing all these experiences to naturally feed into a new path of research and creative process. There are still strands of the artist’s previous subjects and visual languages at play—the industrial is ever-present, reflective and metallic finishes remain, and cars still weave through the work. So, as well as presenting as a complete triptych installation in itself, Manual Labour also documents how the artistic process—and self-identity of the artist—changes over time in a compellingly biographic way. And, reflected back in those shining surfaces, it also offers the possibility for viewers—of any gender—to consider their own relationship to the issues of labour, class, work, and power that Perry explores.

Hannah Perry’s show will be on at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art until 16 March 2025.

Words by Will Jennings