During the current lockdown, I have found myself with more time than usual to reflect on life. Whether it’s existential rumblings or plain old millennial narcissism, I have been taking stock of how far I’ve come and wondering where I’m headed. Of course, with a third of the world’s population in isolation, I am hardly alone in my recent self-analysis, but there is something else driving my introspection. In just under a week’s time, I will turn thirty.

It is a landmark birthday, and one that tips me into a new decade that I am not entirely sure I feel ready for. Spent alone at home, as far from friends who are just a five-minute walk away as I am from loved ones scattered in cities across the world, it is certainly not one that I will forget. The cliché goes that you’re only as old as you feel, but the ways in which we understand ourselves are inextricably bound up with how we are perceived by others.

As a schoolgirl, I saw those over the age of thirty as practically elderly, but it’s not just children who are quick to pass judgement. The creative industry has an obsession with youth, and it shows no signs of abating. “30 Under 30” or “40 under 40”, rehashed by media brands from Forbes to Apollo, don’t just draw a line in the sand between the decades, they build a wall between them. Like many myths, they feed upon the inadequacies of others, and fuel us to question our own achievements, or lack of. No wonder I am already beginning to feel old.

The fixation on age can create real barriers too. No Entry was set up by writer Joanna Walsh last year to challenge age-barred opportunities in the arts and raise questions about access. She uses Twitter to call out competitions and open calls that specify an age limit, arguing that there are a multitude of reasons why an artist might start later. As she puts it, “age-limited calls may cut off ‘young’ writers who’ve met personal, financial, health or cultural barriers.”

“When the art world says ‘young artist’, what it often means is ’emerging artist’, and the two need to be disentangled”

Financial constraints cannot be overlooked; an artist who must fit in their practice around a paid job will inevitably fall behind one who has the luxury of focusing on it full-time. The time and space to work on creative pursuits at a young age imbues a certain type of confidence. Others can only afford to go to university later in life, or are able to pursue their passion only after retirement. Notably, it is often women who are excluded from focusing on their career early on, as they take on the bulk of the care work within a shared home.

When the art world says “young artist”, what it often means is “emerging artist”, and the two need to be disentangled. These prejudices have been thrown into stark relief during this period when no one is able to do very much work at all. We have collectively been forced off the treadmill. Those who have only ever known what it means to accelerate are suddenly suspended in motion. Now they too must experience what it feels like to lose time as easily as a spilled glass of water.

This is what it means to stand still. The present emptiness reminds me of the days after my mother died three years ago. I tidied cupboards and made lists of films I would watch, in a failed attempt to counteract the time I mostly spent doing nothing at all. When I left the house then, I was shocked that people were still going about their daily lives, and that the world hadn’t come to a halt. Now it has. I thought then that I might write something I would value in years to come, and which might help me to move forward with my creative aspirations, but of course I didn’t. I can’t say that I regret it, but I do wish that I could change the bitter disappointment that I felt each day when the words did not come.

“What we were all racing towards anyway, when short-term obstacles can derail an entire existence?”

Time is precious, but it is worth more than achievements that can be tallied up so neatly upon a page. The current crisis has set many artists and other creatives back by years, as outlined in an article published in The Guardian this weekend. Titled “Stressed, sick and skint: how coronavirus is hitting arts workers”, it offered first-hand accounts from creative professionals on the impact of the lockdown on their livelihoods.

One thirty-eight-year-old writer, who was just hitting their big break with a play newly opened in the West End, describes their frustration at the long-term impact that the early closure will have on their career. “The financial loss from the cancellation of two plays, a TV and a film gig has hit the tens of thousands. That makes it sound as if I always earn at this level—I don’t and I haven’t. I’ve been working hand to mouth and now, when it looked as if I might finally be able to breathe, I don’t know when I’ll get paid again.”

The precarious and unpredictable nature of the arts has been fully exposed, as has the narrative that favours the young over the old. I am left wondering what we were all racing towards anyway, when short-term obstacles can derail an entire existence. We are encouraged to pit ourselves against one another in pursuit of our goals, but there aren’t enough opportunities to go around. Now there are even fewer routes to professional success, and who will survive long enough for them to return?

I will take my first step into a new decade in the hushed atmosphere of a collective lull. I hope that it will help me to assess myself and my achievements less harshly. This period will also serve as a reminder that we are all only ever a few steps away from losing out or missing that chance. The fragility of time has never been more apparent.

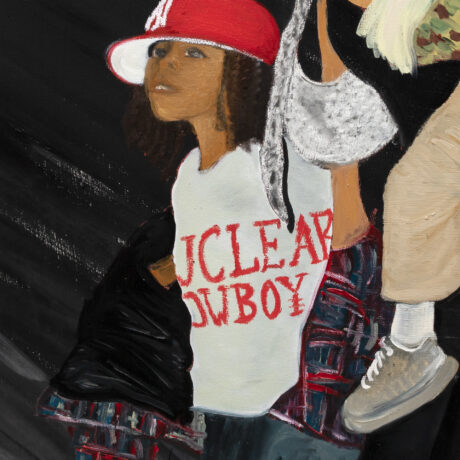

Are We There Yet is a fortnightly column by Louise Benson. Top image © Miguel Santa Clara