The Noon Complex, 2016. Photo: Frank. Kleinbach/Kunstmuseum Stuttgart

An airborne camera pans up the dramatic reverse pyramidal staircase leading to the rooftop patio of the Italian modernist masterpiece, Casa Malaparte isolated on the Isle of Capri. A harsh midday sun floods over the freestanding white wall that curls around the open patio, while the soft nude figure of Brigitte Bardot basks prostrate like a lizard, head down, a copy of Homer’s Odyssey propped on her behind like an intellectual fig leaf. Or at least that’s the scene rendered in Jean Luc Godard’s 1963 film, Contempt (Le Mépris).

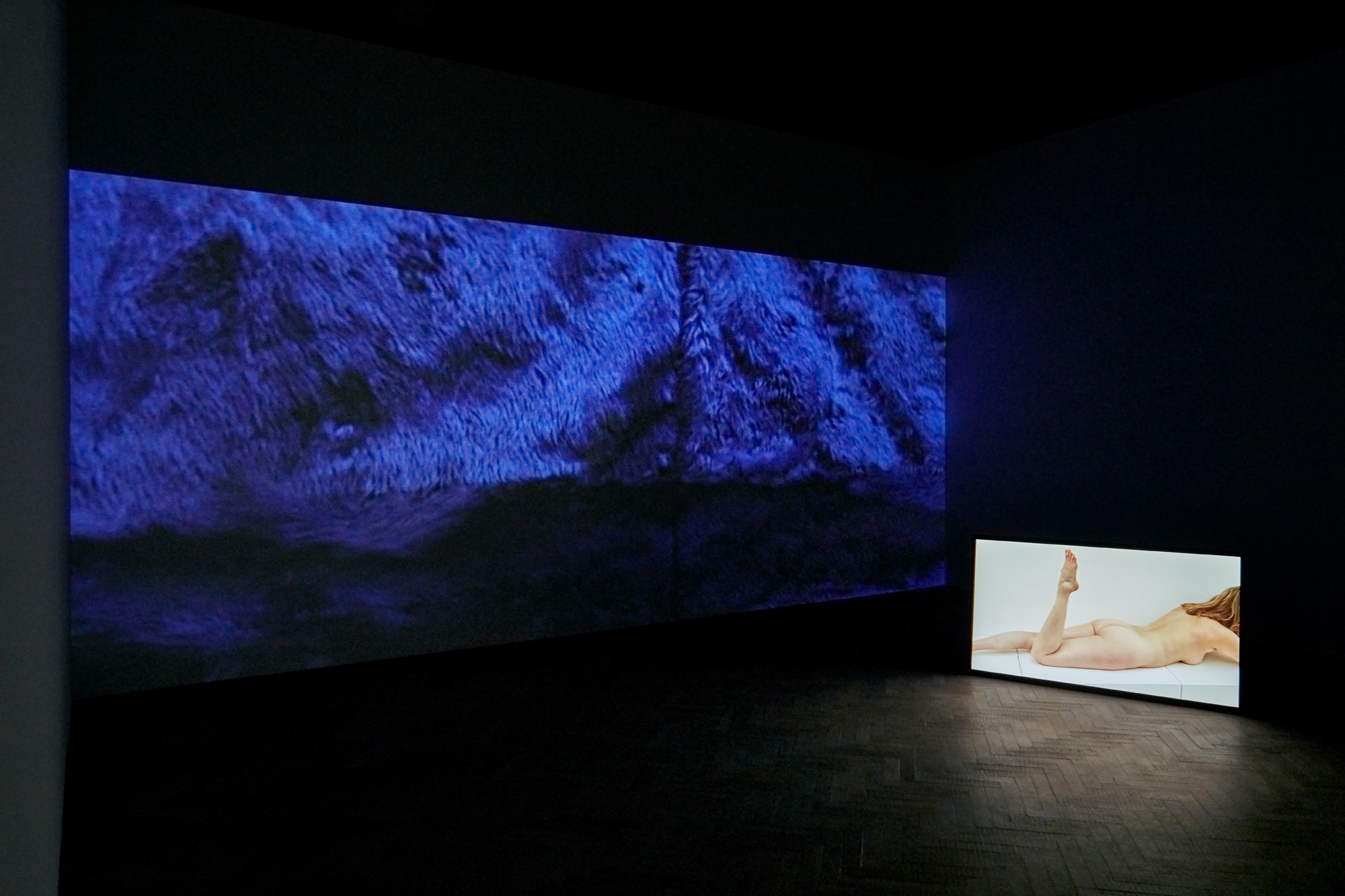

In the back room of Thomas Dane Gallery in London, things appear differently. The Noon Complex is comprised of three screens, two wall projections and one floor monitor that hinges in the fold between the walls, partially obscuring either screen depending on the viewer’s vantage point.

“The female body, architecture and the male gaze merge into a sun-streaked landscape of desire”

The film oscillates from one side of the room to the other, encouraging its audience to roam the gallery space as Godard’s camera likewise careens over the dramatic Italian cliffscape, or concentrates lustfully on a constructed stage set in which the female body, architecture and the male gaze merge into a sun-streaked landscape of desire.

Genealogies, installation shot, Thomas Dane Gallery. Image courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Simon Preston Gallery. Photography: Luke Walker.

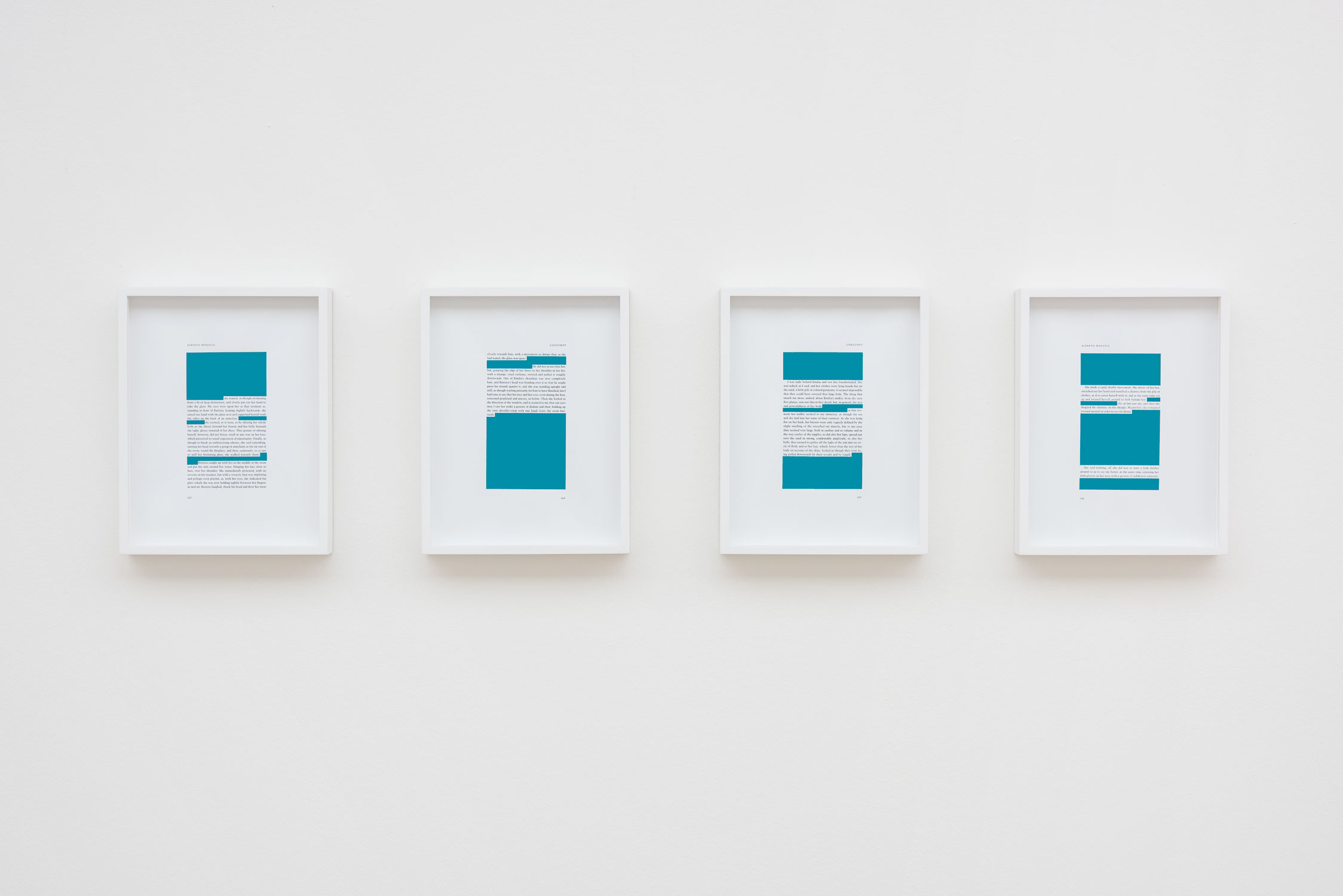

Backstory, the current exhibition organized in collaboration with Simon Preston Gallery, shows New York-based artist Amie Siegel dissecting Godard’s most commercially successful endeavour, among other loaded cultural productions. Siegel follows the film back to its roots, to the book Il Disprezzo (A Ghost at Noon) penned by the Italian novelist Alberto Moravia almost ten years before (itself an existentialist homage to The Odyssey), and traces the constellations of male desire present in the original text with Body Scripts. A series of 2D works on paper highlight passages of Moravia’s novel and focus exclusively on the text’s female protagonist, while overlaying surrounding unrelated text in a field of blue: allegedly “the average colour” of the Tyrrhenian Sea surrounding Capri.

Body Scripts is the first work viewers encounter (with the exception of a new piece just outside the space: a three-layered collage of various Freud museums in London, Vienna and the Czech Republic); it also quite literally sets the stage for the ensuing work, The Noon Complex

. Sandwiched between the two is Genealogies, a video essay that traces the connecting threads between Casa Malaparte, Godard’s film, the tri-museums of Freud, the iconic 1972 documentary film Pink Floyd at Pompeii, among other cultural productions.

“I am interested in this constellation of associations on male authorship and engagement with the female form; as well as image as artefact, originality, homage”

Like Godard’s roaming lens, the goal of Siegel’s work is kept inexplicit. “I’m not attempting to critique these works, and my response certainly isn’t a value judgment—rather, I am interested in this constellation of associations on male authorship and engagement with the female form; as well as image as artefact, originality, homage…” Archival but also expository, Genealogies can be thought of as an architectural project—one that stacks a network of overlapping themes, in order to see what other comparisons might emerge when the scaffolding is removed.

Siegel sees a definite link between her own methodology and Freud’s metaphors on psychology, but she takes care to point out the site of diversion: the fetish. For Freud and many other prominent twentieth-century artists and intellectuals, the crux of their so-called “genius” stems from a reckless and deviant obsession with their subject matter. It is also true that for many of the cinematic geniuses—from Roman Polanski to Woody Allen, and of course Godard—that fetish just so happens to be the female body on the big screen, and the psycho-sexual power of being behind the camera’s gaze.

Siegel wants to flatten the field. With the show’s equally layered and labyrinthine-like structure, the artist draws attention to this complex network of cultural capital, freely appropriated by advertising and media groups under the guise of “homage”. Of particular interest is the process by which objects and images of cultural production become layered over time, forming a network of associations that otherwise appear unrelated (a German fashion house’s luxury cologne advertisement and Italian modernist architecture; a 1960s English rock band and the ruins of Pompeii, its reified position in western history’s collective consciousness).

“The pace slackens, a reference to that monstrous point of day where shadows disappear; when, legend says, the human soul becomes its most vulnerable”

These collisions of high and low culture—typically enabled by purchasing power or social clout—form the parameters of Siegel’s investigative practice, which operates like a sort of cultural forensics. Walking up and down the twentieth century’s cultural pecking order, she collages case studies in order to dismantle the hierarchy as we know it, re-presenting her findings in what the artist refers to as a “democratized landscape”. Pressure points frequently land on the relationship between the female body, architecture and male pleasure, as well as culturally-produced ideas of authenticity.

Things come full circle in The Noon Complex. The pace slackens, a reference to that monstrous point of day where shadows disappear; when, legend says, the human soul becomes its most vulnerable. A disappearing act is also at work here, in Siegel’s re-presentation of the scenes honing in on Brigitte Bardot in Contempt (Le Mépris).

Although her voice remains, Bardot’s body has immaterialized, reducing Godard’s choreographed scenes to their primary architectural element, and exposing Casa Malaparte’s role as foil in creating a cinematic space of desire. “It’s not that she is not there, but Bardot has become an apparition to some degree,” explains Siegel, who re-staged the character for the trio of works in Backstory, which originally appeared as the second part of the artist’s solo show at Kunstmuseum Stuttgart in 2016.

Following the descriptions of male desire as seen in the gouache-coated Body Scripts (2015), the actress performs Bardot’s character in the generic white cube space, whose dimensions mirror that of the Casa. Its plush blue velveteen sofas and sea views are replaced with upturned pedestals and a quick peek into a gallery storage closet, which remains rooted through the monitor on the floor even as the film projection jumps between walls. The Bardot surrogate’s movements are replayed as the film switches between its French and Italian soundtracks, revealing the striking difference of their emotional impact.

A recurring theme in Siegel’s reference points is the roaming camera. Dislocated from its subject, the cinematic gaze is free to roam unknown territory, often taking a particular fixation with a foreground detail or background affair as it pans across a larger scene. The ambivalence of the tracking camera creates a collision site for multiple viewpoints. The scene becomes porous, absorbing the desires and suspicions of the viewer; here, truth and fabrication mix freely, the divide between them seeming to disintegrate. Backstory behaves similarly, as a hallucinogenic space uninterested in disentangling principles of real and fake, originals and copies—but obsessed with the sticky spaces of their overlap, and the cultural mythologies incubated inside.