There is a debate ongoing in Beirut about a derelict Brutalist building named “The Egg”. Built in the 1960s by Lebanese architect Joseph Philippe Karam, due to be part of the extensive Dome City Centre, it was designed to be the largest cinema in Lebanon. During the Lebanese civil wars, it was used as a bunker (as were many cultural buildings, such as the National Museum of Beirut, where a sniper hole can be seen in their mosaic of the Good Shepherd), and has remained as an abandoned monolith throughout the post-war reconstruction. Akin to the conversation surrounding Beit Beirut (a restored Barakat building, preserved in its damage, as the “museum of memory”), local citizens are divided between demolishing “The Egg”, or keeping the war-scarred structure as a symbolic reminder of the past.

The city’s landscape is one of contrasts, it is an exciting and chaotic environment, gentrifying gradually, with most of the formerly destroyed center now rebuilt or restored. Moving through Beirut by car (there is no public transport system), traffic is often noisy and jammed, each area changing rapidly when moving from place to place. Overheard conversations, even sentences, are a combination of French, Arabic, and English. The art scene is similarly diverse, with a coalescence of commercial galleries, national museums, public institutions, private collections, and the burgeoning of a younger, more grass-roots scene, with artists moving from across the Middle East to live, study, and work in the city.

“I wanted to give soul to a place that didn’t have one… Downtown is beautiful, but there is no soul, no life.”

The combination of luxury developments alongside bullet-riddled buildings is particularly evident with the development of the Corniche seafront, which overlooks the Mediterranean. In the 1970s and 80s, this strategically important area was synonymous with a battle dubbed “the war of the hotels”. In June, interior architect and artist Jad El Khoury—who notably painted the façade of the desolate Holiday Inn tower with a mural titled War Peace in 2015—transformed an abandoned, war-torn tower block into the Burj el Hawa, installing colourful striped curtains in each of the 400 windows, which flapped in the sea breeze, as if dancing. “I wanted to give soul to a place that didn’t have one,” he has said. “Downtown is beautiful, but there is no soul, no life. The balcony shades are elements from working-class neighbourhoods—that’s where there’s life.” The Burj el Hawa was removed, but documentation from the project can be viewed at The Alternative Artspace at Platform 39 gallery in Ashrafieh until August.

- Nathaniel Rackowe, The Shape of a City, Letitia Gallery

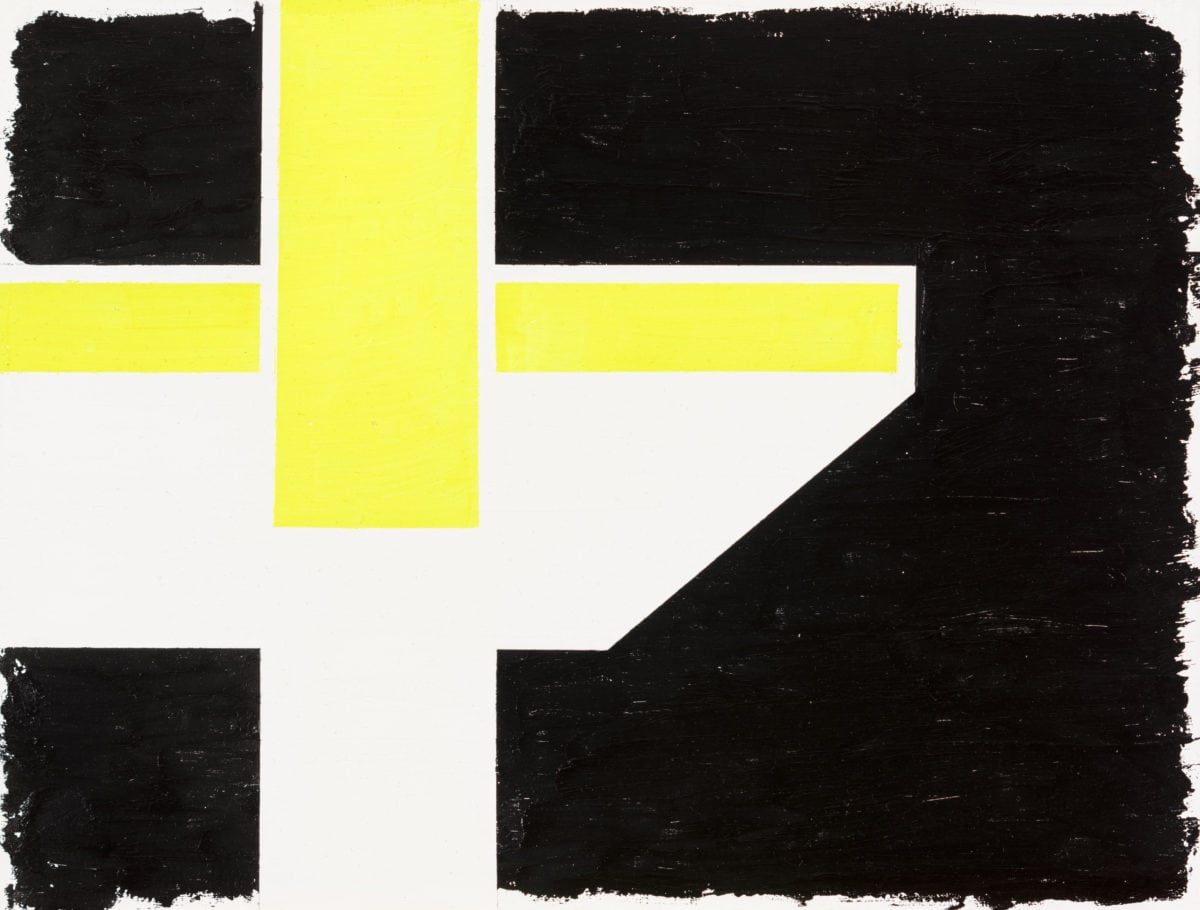

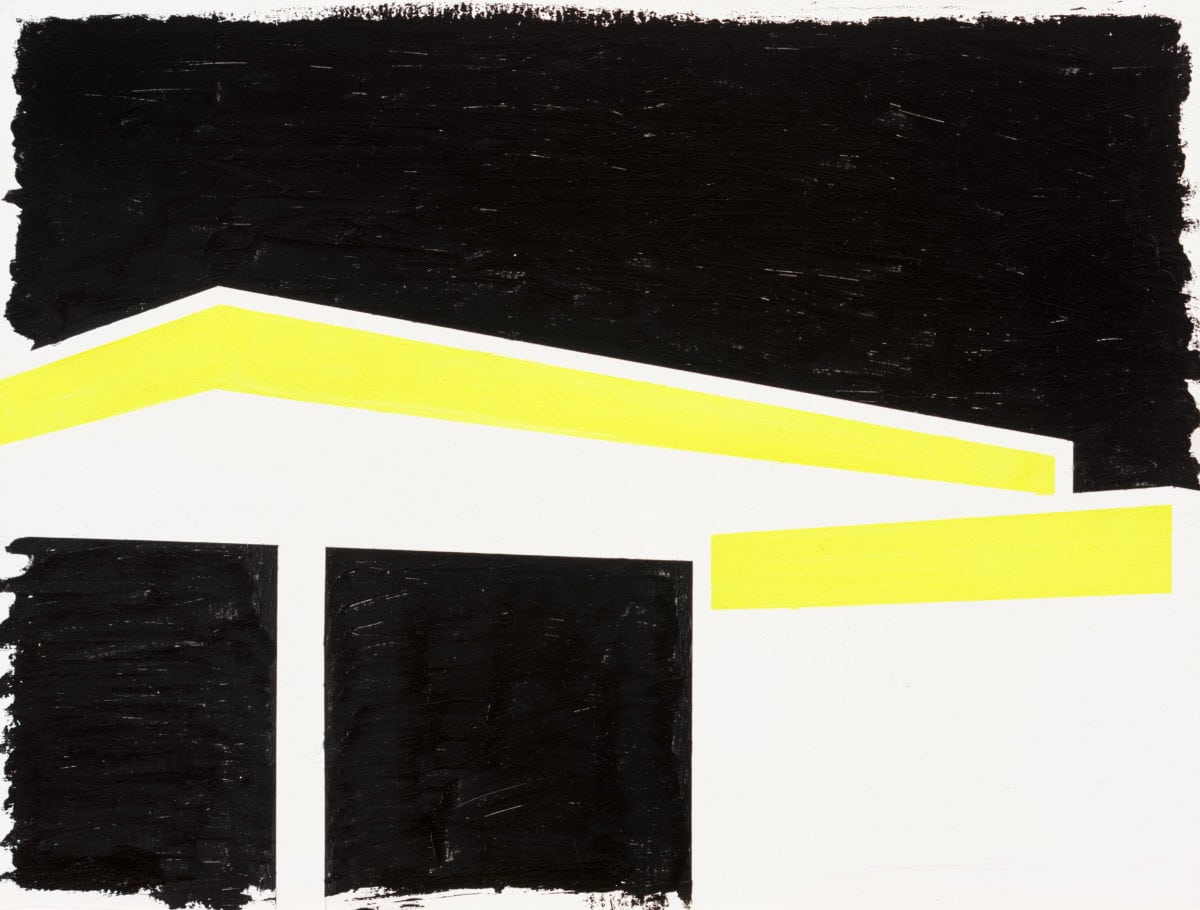

A handful of commercial galleries—Agial Art Gallery, Artspace Hamra, and Saleh Barakat Gallery—are located in the Hamra neighbourhood, along with Letitia Gallery, which was founded in February by Annie Vartivarian and Mohamad Al Hamoud. Their current exhibition, The Shape of a City, features new work by the British artist Nathaniel Rackowe. Known for his minimal, modular sculptures, often comprised of dichroic glass, aluminium, and light, Rackowe responds to environments by working with the literal and tangible fabric of the city.

For Beirut, it was cement blocks, fluorescent lighting, and corrugated GRP roofing sheets; functional objects and materials all sourced from local stockists and factories. As a way of accessing and engaging with a more varied audience, Letitia Gallery have been developing public sculpture commissions. Rackowe’s Black Shed Expanded is in the square by the developing Beirut North Souks department store, an evolving lattice grid building designed by Zaha Hadid. His steel structure LP46 sits in Martyrs Square, just across from the host venue of the Beirut Art Fair (Le Grey Hotel), and a short stroll up to the beautiful turquoise minarets of the Mohammed Al-Amin mosque.

Public art institutions are rare in Lebanon, but after his death in 1952, the Lebanese collector Nicolas Sursock left his palace with the intention that it be turned into an art museum. The first iteration opened in 1961, and after a period of closure, re-opened again in 2015. Along with temporary exhibitions (they recently showed Zad Moultaka’s ŠamaŠ commission for the Lebanese Pavilion at 2017 Venice Biennale), the Sursock hold a permanent collection of modern and contemporary art. Highlights from their current hang included Laure Ghorayeb’s Beirut Calls the Future Generations (2011)—three assemblages composed of drawings, found objects, press cuts, and photographs, that encapsulate aspects of her personal life and Lebanese history, spanning 1920-60, 1960-75, and 1975-1990—along with a series of works on paper, tapestries, and paintings by the Beirut-born painter and poet Etel Adnan.

The non-profit organisations Ashkal Alwan and Beirut Art Center, located in converted factories in the industrial area near Jisr el Wati, embody a more grass-roots approach. Curator Sandra Dagher and artist Lamia Joreige initiated the center in 2009 as a platform for experimental art, and have exhibited artists including Emily Jacir, Mona Hatoum, and Harun Farocki. Founded in 1993, Ashkal Alwan curates exhibitions in Lebanon and internationally. Their manifold programme includes the Home Works Forum on Cultural Practices, publication of literary and artist books, residency programmes, and a video production and screening program.

Their interdisciplinary arts study programme Home Workspace Program was launched in 2011, inviting cultural practitioners to study with them for nine months in order to develop their critical skills and practice. The space itself is open for anyone who wants to work there, regardless of their involvement in the program, and includes an incredible indoor garden area; a small fountain surrounded by a variety of plants and succulents. The library is also one of the only dedicated art libraries in Lebanon, although the Sursock are hoping to make their archive publicly accessible.

In terms of private collections, an impressive new venue worth visiting is the Aïshti Foundation, which houses the Tony and Elham Salamé Collection, situated just north of Beirut in Antelias, looking out over the sea. Designed by Ghanian-British architect David Adjaye

, the striking building with a red, aluminium geometric façade, includes a shopping mall, restaurant and cafes, a spa, and a rooftop bar, in addition to a vast, four-storey gallery space (where two of the floors are double-height). Their current show, The Trick Brain, curated by the New Museum’s Massimiliano Gioni, reads as the great and good of the contemporary art market, from Isa Genzken, Cindy Sherman and Wolfgang Tillmans to Adrián Villar Rojas, Danh Vo, and Nicole Eisenman.

“Eating, too, is an art form in Lebanon.”

Eating, too, is an art form in Lebanon. Meals involved baskets piled high with bread, bowls of fattoush, hummus, falafel, baba ganoush, manakish, tabbouleh, za’atar man’ouche, various cheeses… and that’s just to start. The seafood—seabass, squid, snappers—is fantastic and fresh. Desserts, including basbousa, kuafeh, and baklava, are delicious, and usually accompanied by refreshing platters of watermelon, cherries, and cantaloupe, and a round of Arabic coffee. Needless to say, this is only scratching the surface of what Beirut has to offer beyond the art scene. When you’re in the city you’ll hear about evenings spent in the bars of buzzy neighbourhoods such as Gemmayzeh, or the revered nightclubs, long days spent at the beach, weekend trips up into the mountains, and much more.