Many of the works of art that come to mind when we think of angst are paintings: most obviously Munch’s iconic The Scream. You can’t help but think of Francis Bacon too, whose fierce depictions of human bodily vulnerability evoke the easy destructibility of our fleshy forms and the tortured souls which reside within them. But there are many angst-ridden works to be found in the world of drawing, where frenzied, densely-packed marks speak of pure emotion, and the artist’s dark imagination and inner world can be transported onto the page with immediacy.

Here are seven artists whose drawings call to mind our “Summertime Angst” theme, many of whom are featured in the latest edition of Phaidon’s mammoth tome to drawing: Vitamin D.

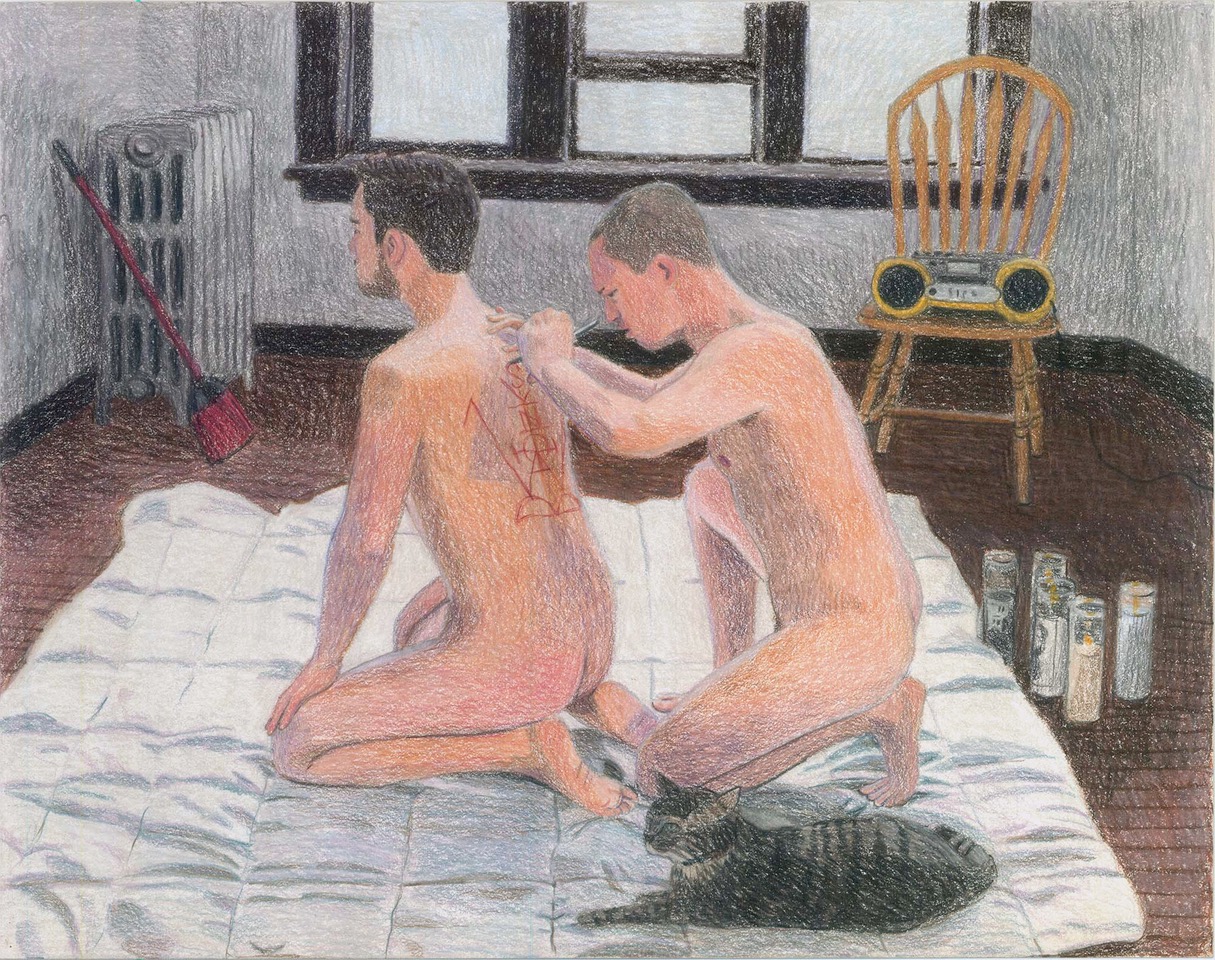

Burgher’s works have just the right amount of ambiguity to make them truly angsty. Creating a fictional “mystical cult of queer sexual energies”, his drawings are bright, playful and, in many cases, wonderfully inviting. In lots of his delicately coloured works, nude figures converse in natural settings, and there is a vibrant psychedelia to his more patterned, abstract works. But, in keeping with our expectations of cults, there is a dark side which rears its head here and there. In No Irreversible Sentences 2, one character is seen drawing on another’s back—is he using pen, paint or blood to make his marks? On first glance, it’s difficult to tell.

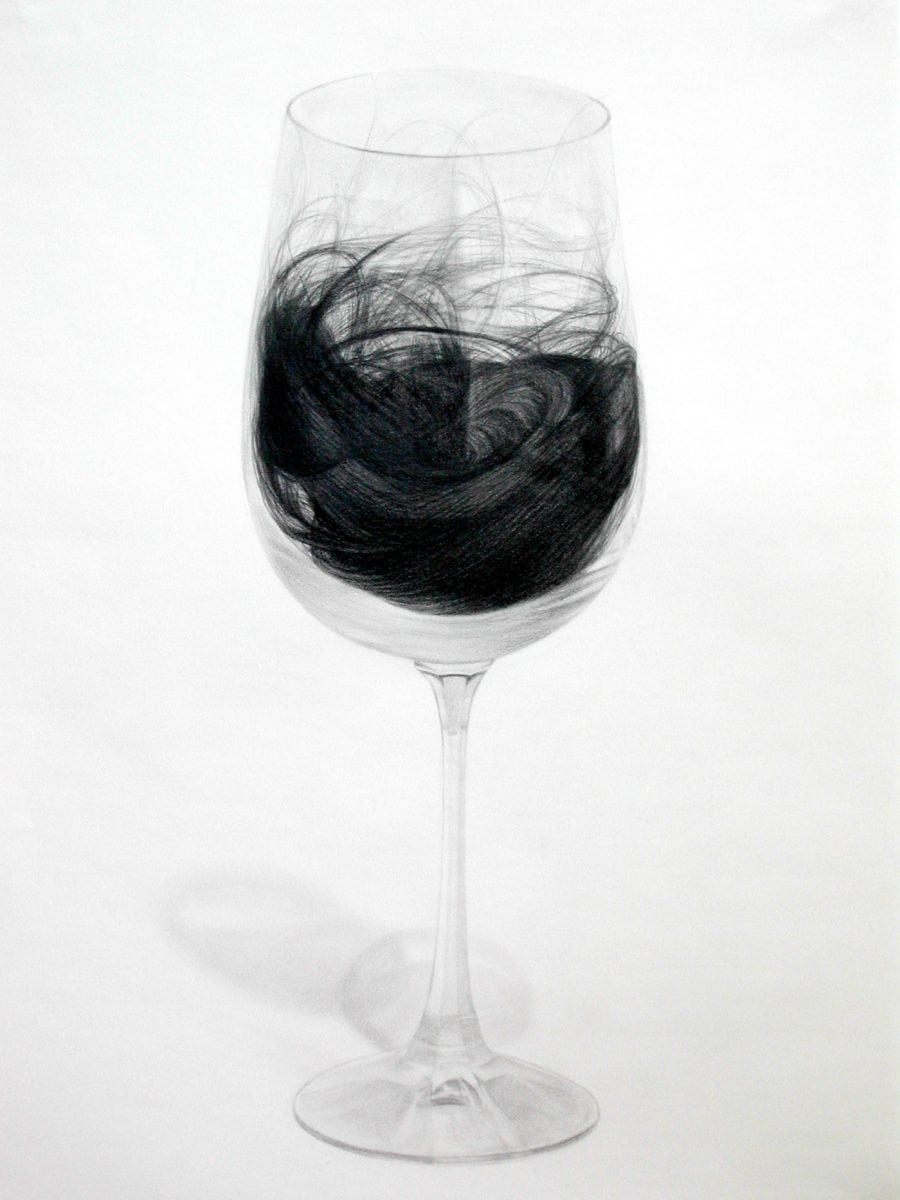

- Hong Chun Zhang, Napa California, 2004

- Paper, 2007

Excuse me, I think I’ve found something in my food… Featured in our “Summertime Angst” issue, Hong Chun Zhang’s intricately drawn objects are stomach-churning: the artist often focuses on food which is filled with human hair. There is something incredibly beautiful and dreamlike about the way the items are formed, however, with thick coils of hair (rather than the lone strand we all fear finding lurking in our dinner) and the works therefore simultaneously seduce and repulse.

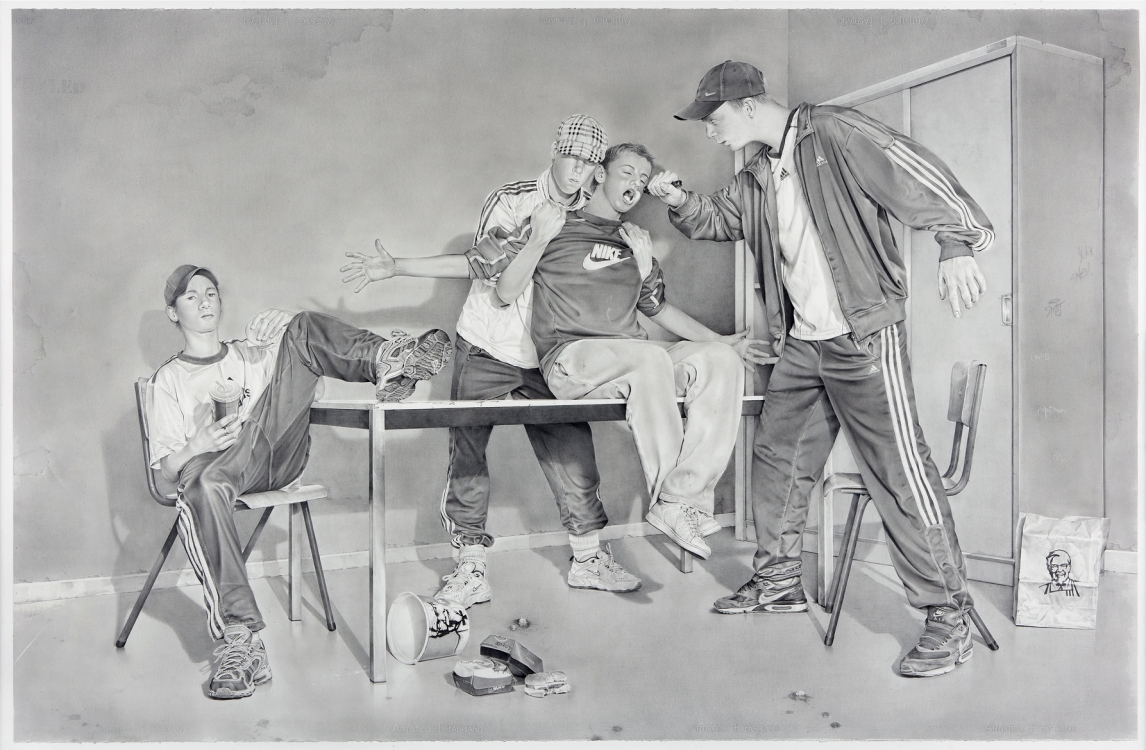

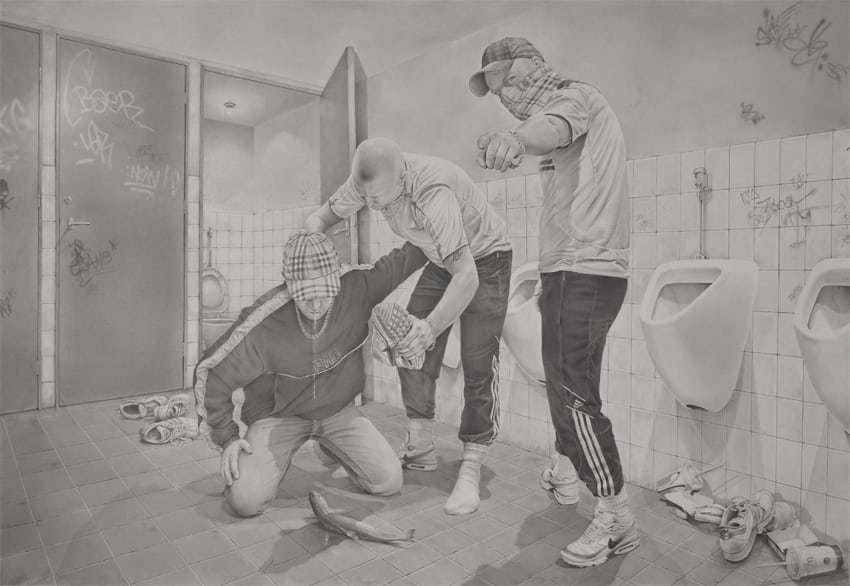

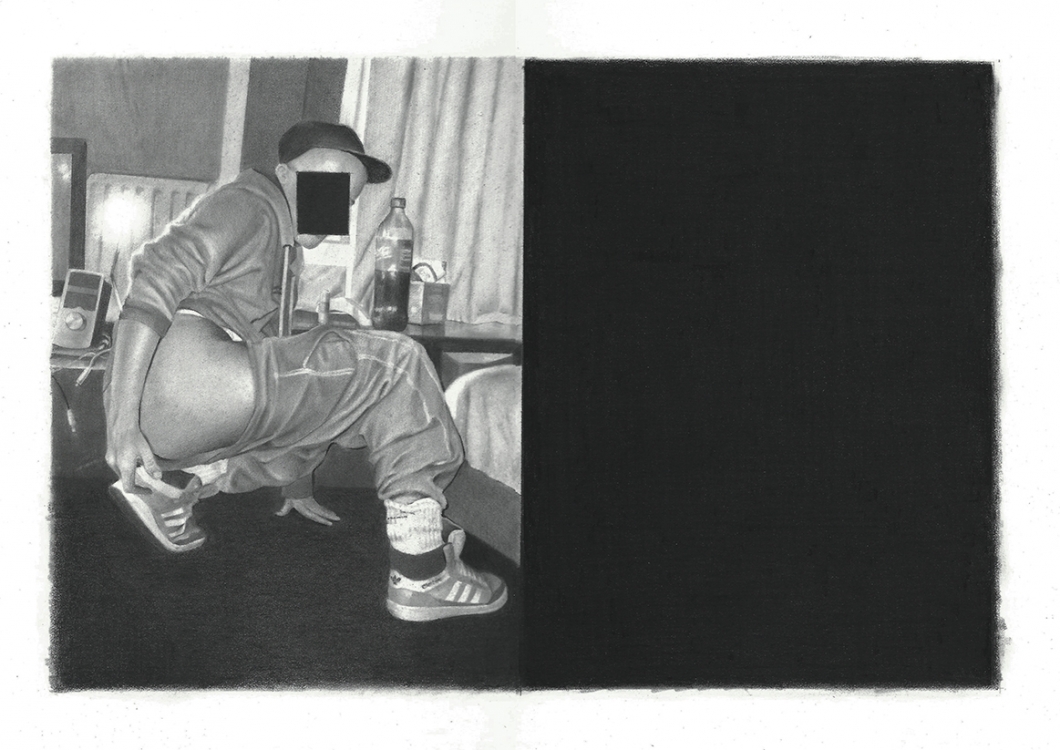

- David Haines, Adidas Boys, Investigation into Digestible and Indigestible Substances, 2009. Pencil on paper, 220 x 140 cm

- Liquid Myth Nike Air, 2008. Pencil on paper, 140 x 240 cm

David Haines’s pencil drawings of tracksuited teenagers play into our instinctive, collective fear of youths. His images, many of which are sourced from photographs on the Internet, invoke a gut response—with instantly recognizable Burberry check caps and scarves, and Adidas’s triple stripes running the lengths of arms and legs. The figures engage in threatening and mildly surreal behavior—in one work, located in a public bathroom, two boys stand over another who looks as though he has just vomited up a live fish. The images have threads of gay erotica running through them as well, in contrast with the type of masculinity inherent in the adolescent group mentality. Of course, the line between reality and fiction is blurred—are we getting a rare inside glimpse of the teenage world or are we merely seeing our own fears of it? I find it hard to look at these works and not think of David Cameron’s oft-mocked idea that we should all “hug a hoodie”.

Nik Christensen’s works are created with ink rather than pencil, but their monochrome finish and geometric forms often see them likened to drawing. The scenes depicted by the artist are sliced up almost to the point of abstraction, as though reflected in hundreds of shards of broken mirror. Occasionally we have a solid glimpse of human life, appearing small and lost amid the surrounding chaos.

Exploding, pustulating biological forms are rendered in colourful, wondrous beauty by Vidya Gastaldon—and her works, though grim and angsty, also verge on comedy. Her strange creatures have googly eyes, which give them a Halloween feel as well as a dose of cuteness. If we were to give a physical form to our angst, and attempt to come to terms with it, these friendly blobs would be a good place to start.

The angst in Cameron Robbins’s works is conveyed through mark-making rather than objects and figurative forms. His Wind Drawings are frenzied and flyaway, suggesting a passing storm, a flurry of movement and, ultimately, a sense of physical flimsiness. Everything is in motion, everything is changing, and we are swept up along with it. That, alone, is rather terrifying.

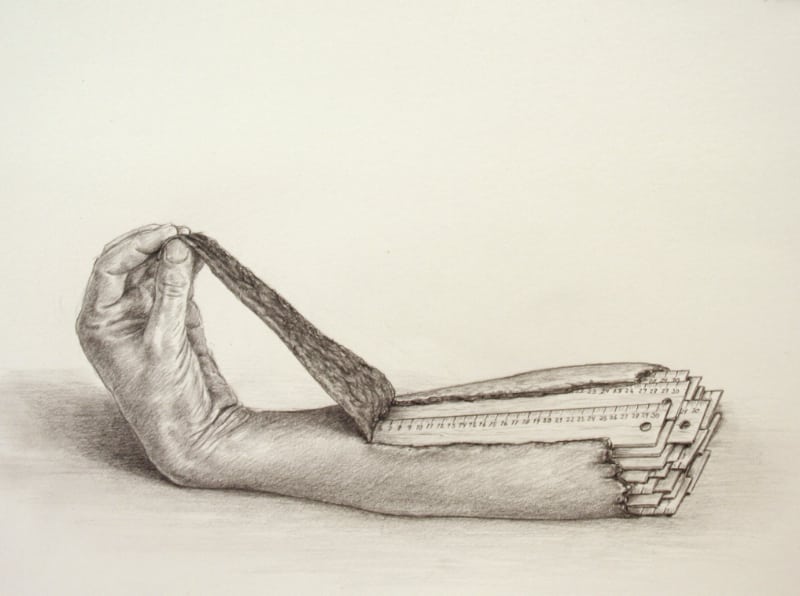

There is a peacefulness to Martin Skauen’s works, which makes their violent content even more unsettling. In one work, the artist draws a hand which gently peels back a layer of skin along the length of its adjoining arm. Inside, a hoard of rulers are stacked up, ready to burst out. In another drawing, a man’s entire face is replaced with a heart—not the smooth Valentine’s Day kind; the bloody organ that resides in our chest. He too looks calm, as though there is nothing unusual about the lump of gristly muscle which sits in place of his face.