As we all know, you can separate people into two main categories: you’re either a dog or a cat person. Period. “But, but…!” some people might protest, as they go on to cite statistics that list mammals nearing some 5,800 species, with insects topping over one million. “No,” I say, digging in my heels. “Cat or dog: which is it going to be?”

For the record, I’m a dog person. (Who can resist their fluffy ears, panty tongues and sheer devotion? And everyone knows you can’t trust cats.) However, for those of you less obsessed with this dichotomy (or rivalry), Phaidon’s new read Animal: Exploring the Zoological World might be right up your street.

Bridging the gap between art and science, this meaty coffee table book brings together hundreds of glossy colour images from various contexts and moments through history, ranging between the zoological and scientific to those from fine art, archaeology, advertising, education and entertainment, each explained with a concise text. They are arranged as facing pairs, often to highlight stark similarities or differences, or to illustrate changing artistic conventions, cultural norms, attitudes and even shifting ideas around morality.

So what can we learn from flicking through this book when the internet can deliver us images of every insect, animal and amphibian under the sun

? The answer is: a lot. It sets into context how our study, depiction and understanding of animals has changed throughout history, and indeed, how our knowledge continues to develop exponentially.

Its introductory essay, “The Art of Life: Depicting the Wonder and Beauty of Animals”, is penned by James Hanken, Alexander Agassiz professor of zoology and director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University (what a title). Academic in tone but highly accessible, it breaks down into digestible chunks exactly what zoology is—in short, the scientific study of animals and their biology—and offers an overview of why we have made images of animals through history, how these have changed and the future of what zoology looks like.

Peppered with fascinating facts, we learn that beetles are in fact the world’s most common and varied species, Hanken citing British biologist JBS Haldane’s description that God must have “an inordinate fondness for beetles”. Either that, or these insects have been getting pretty busy of their own accord (the more likely explanation?). The author also reminds us that we are in a race against time to discover and formally describe animal species before they become extinct—indeed, a recent Guardian article described how humanity has wiped out 60 per cent of animal populations since 1970.

“Humans have been writing books about other creatures since Aristotle’s Historia Animalium. Written in the fourth century BC, it influenced zoology for 2,000 years. Not bad…”

Some of the earliest depictions of animals are to be found in the dark depths of caves, these images usually having been blocked off from the outside world for centuries by fallen rocks, and as such have remained virtually untouched. Take, for example, the Chauvet Cave in France, where paintings date from approximately c.35,000 BC and include horses, mammoths, bison, striped rhinoceroses, panthers, butterflies and cave lions—which are now extinct—as well as human palm prints. Some of these were rendered nearly 5,000 years apart from one another.

Palaeolithic painters would have used fire to observe their art, and this flickering light, combined with the three-dimensional undulating form of the walls would have created the illusion of movement, like an animated film. Even more fascinating is the recent discovery in Spain earlier this year, where paintings within three caves are believed to have been made some 65,000 years ago—20,000 years before homo sapiens even arrived in southern Europe, meaning that our need for symbolic expression may have in fact started with the Neanderthals.

Humans have been writing books about other creatures since Aristotle’s Historia Animalium in the fourth century BC, which organized then available knowledge of animals. It influenced zoology for 2,000 years (not bad). Much later, in the eighteenth century, Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus was the first person to apply binomial nomenclature to the actual naming of species, listing 10,000–12,000 animals in his Systema Naturae (published in 1735). So while today over two million species of living organisms have been named, taxonomists estimate the total number at eight to ten million. Still a lot of work to do.

“The author reminds us that we are in a race against time to discover and formally describe animal species before they become extinct—humanity has wiped out 60 per cent of animal populations since 1970”

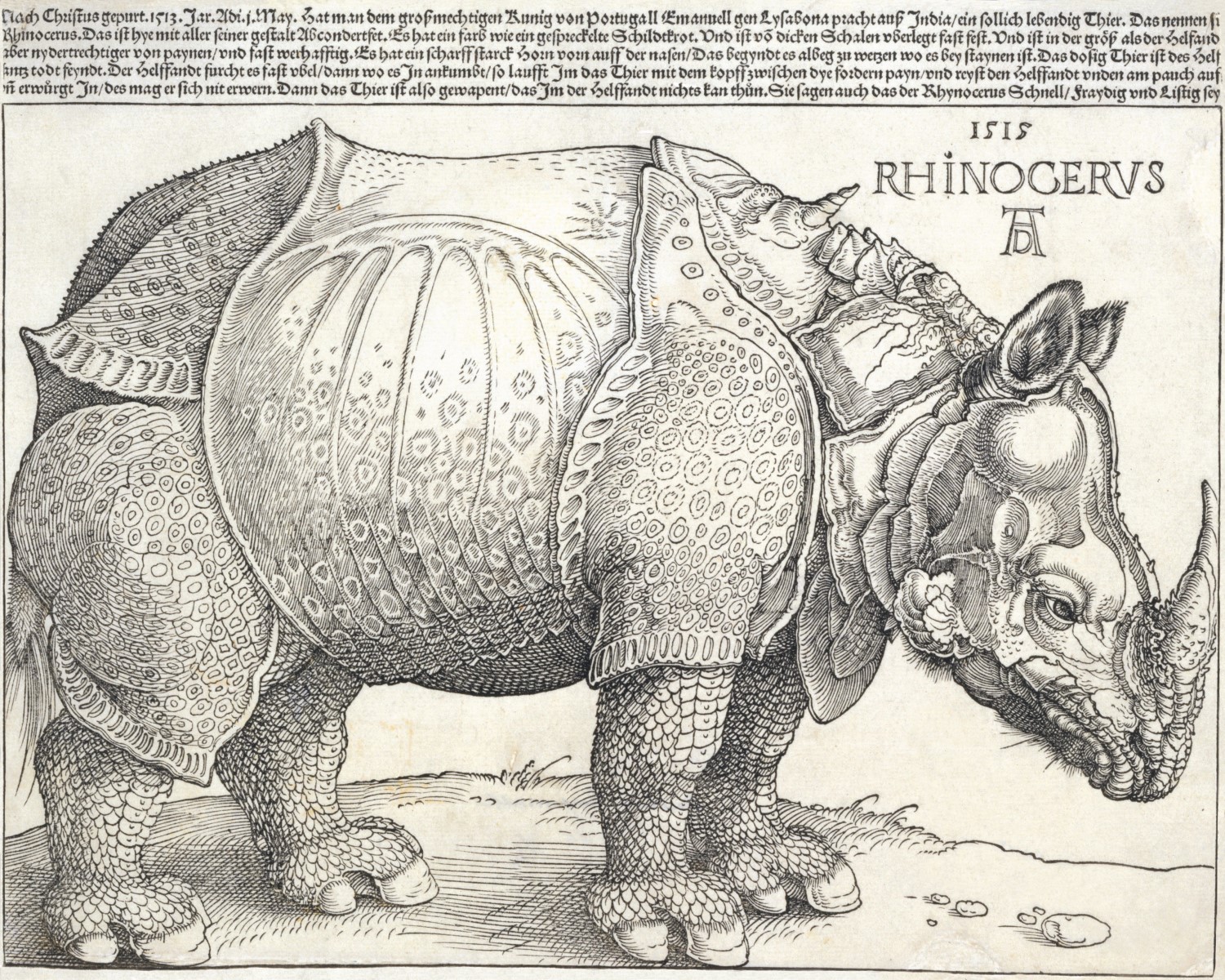

Humans have believed wild and wonderful things about animals throughout history with the help of many of the images reproduced in this book. For Albrecht Dürer’s 1515 woodcut of an armour plated rhinoceros, the German Renaissance master worked from inaccurate spoken accounts and drawings by other artists, having never seen one in the flesh. It’s not so bad, considering: he tried his best, bless him! What else could people do before global travel became the norm? The earliest museums—cabinets of curiosities or Wunderkammers—were amassed by private patrons precisely for this reason, preserving animals, plants, rocks and fossils as relics through which to display knowledge about a world in which most people hadn’t travelled. Some even contained unicorn horns (and who could say otherwise?!).

Eugène Delacroix, Tiger, c.1830. Watercolour. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

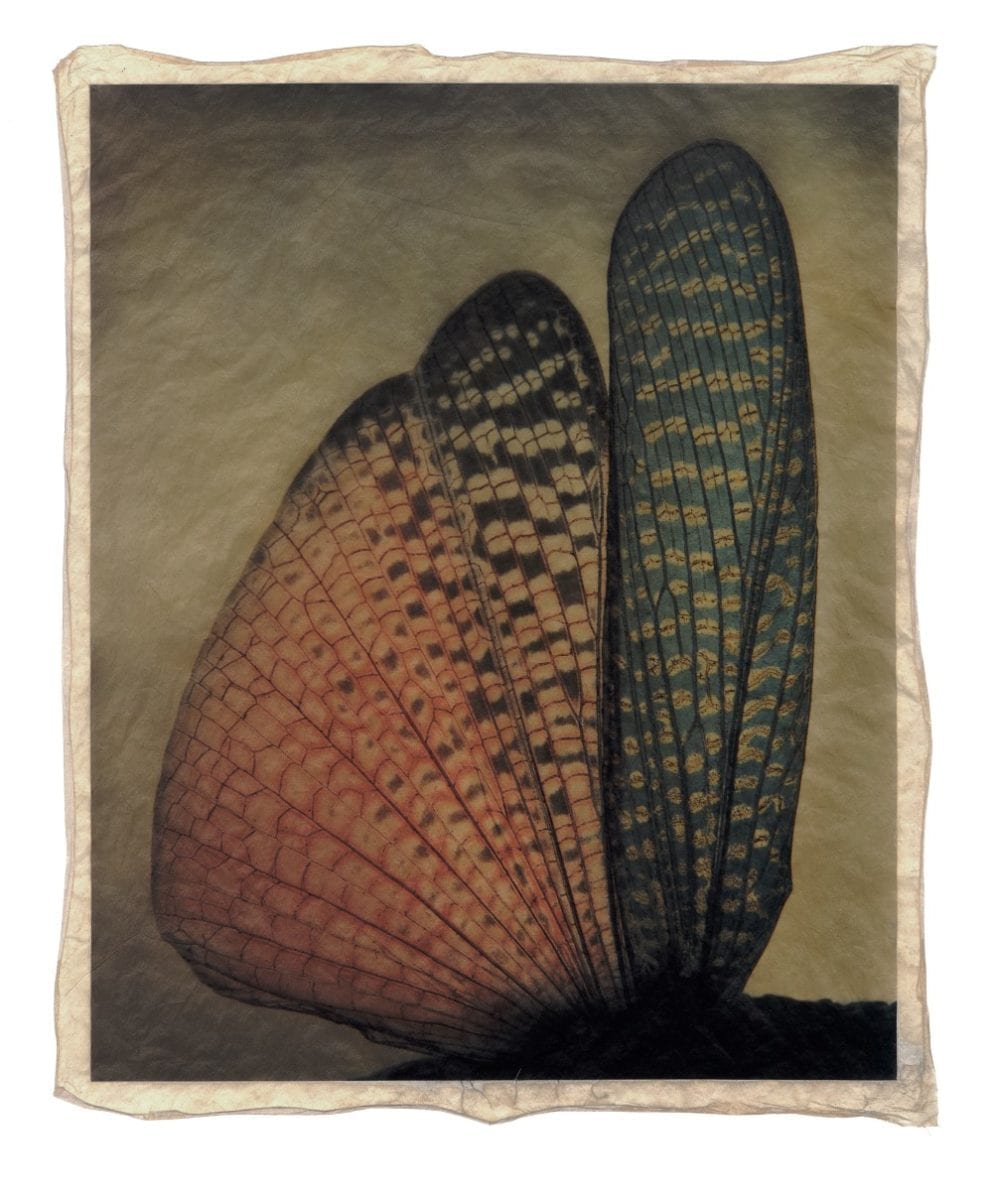

Highlights from the book’s images include Kangaroo and Hunter by an unknown Aboriginal artist from the twentieth century, rendered on a piece of tree bark and portraying a kangaroo who has been speared by a hunter; Itō Jakuchū’s Plum Blossoms and Cranes (1761–1765), a suite of bird and flower paintings on silk, comprising thirty scrolls on which the artist spent ten years for the Kyoto-based Shokokuji monastery; and Wing*Wing Couleur No. 1 (2016) by German artist Gregor Törzs, a photograph printed on delicate Japanese gampi tissue paper to mimic the equally delicate wings of the cicada that it depicts. With further works by Georgia O’Keeffe, Pablo Picasso and Vincent van Gogh, to name but a few, these pages keep on giving and giving.

This is a book that would make David Attenborough proud. If anyone knows him, be sure to buy him a copy for Christmas.

- Gregor Törzs, Wing*Wing Color No.1, 2016, Pigment print on Japanese gampi paper. Picture credit: Gregor Törzs

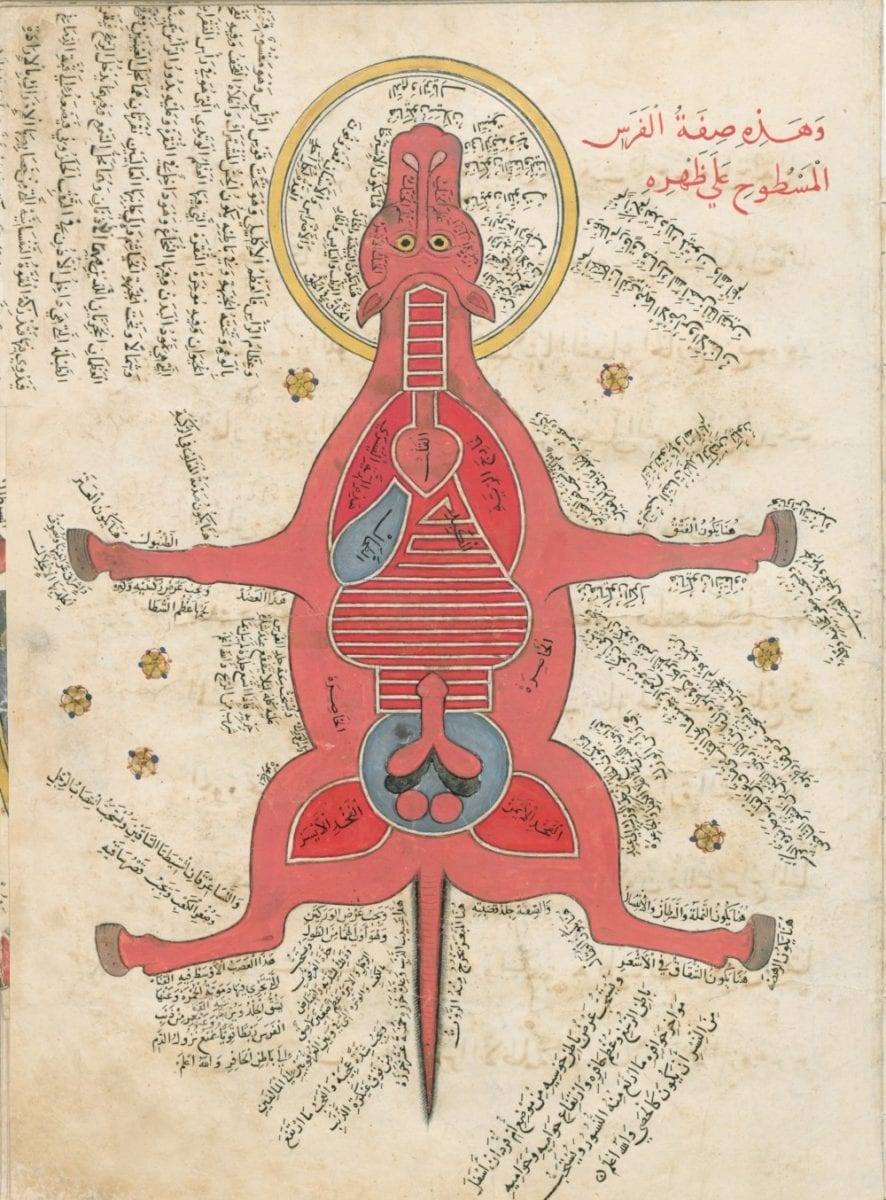

- Unknown, An Anatomical Study of the Horse During the Reign of the Burji Mamluks, 1382–1517,