Posters are capable of many things: selling, informing, instructing, decorating, forbidding. They can reveal flimsy teenage Socialist leanings and recreational drug preferences through tatty Che Guevara and “take me to your dealer” alien images respectively. They are so ubiquitous that they’re largely unremarkable, but their familiarity is a testament to the power of the medium. This humble format has endured over hundreds of years, weathering radical changes in digital communication. Posters are largely unchanged in their aim and format since the nineteenth century: mass produced, printed, pasted, and designed with the intention of speaking as directly and succinctly as possible with its intended audience.

While today’s posters, displayed in public places such as transportation networks and busy streets, are often digital files that have the capacity to loop and animate, their design considerations are largely the same as they ever were for their printed counterparts. For the vast majority of posters, this means a skilful marriage of colour, text, and image, presented as a rectangular call to action, be that to take more care or be more vigilant, act in a certain way, buy something, visit somewhere or view the world in a new way. Paper or PNG, posters are as influential as ever.

“This humble format has endured over hundreds of years, weathering radical changes in digital communication”

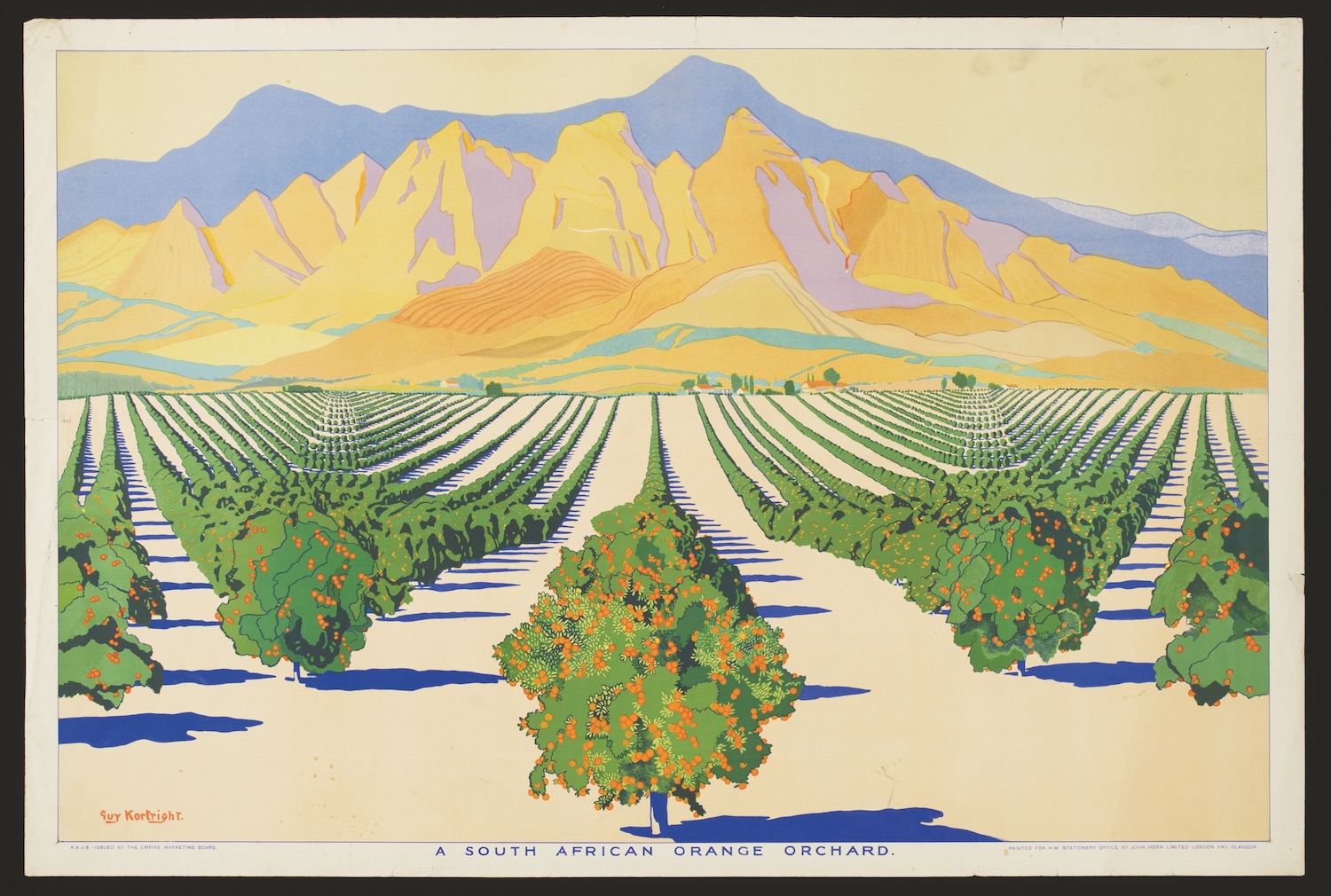

This rich history is made more evident than ever in a new book from V&A Publishing and Thames & Hudson, simply titled The Poster: A Visual History. Through its presentation of 300 images, drawn from the V&A archives in London, it shows that the poster’s enduring success can be put down to the fact that they’re precisely created to charm their viewers. Frequently quite beautiful, they can also seduce with wit, humour or shock value. They aim to grab the casual passerby, whether or not they agree with their message.

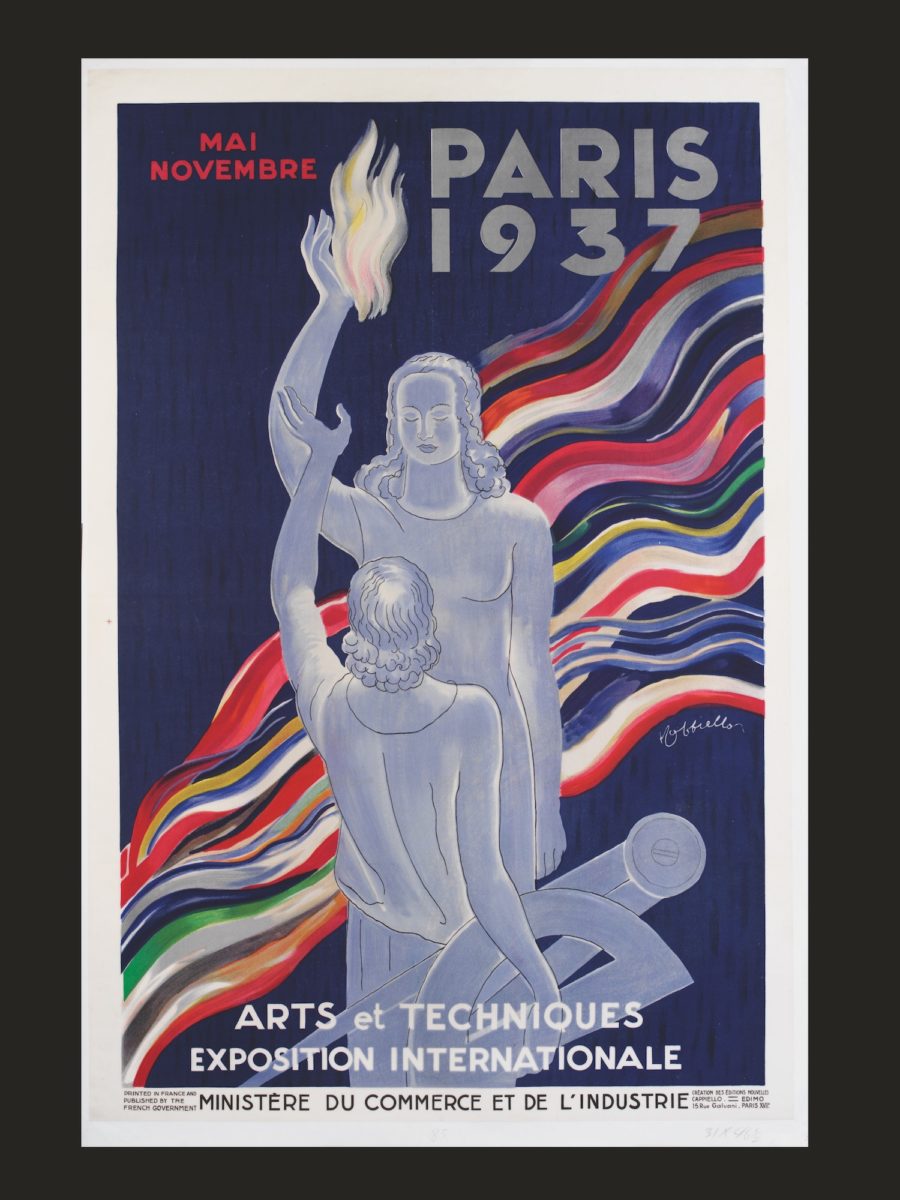

Looking back at the breadth of these historical posters, it becomes clear that these artefacts don’t just reveal the evolution of design, image-making, typography and print technologies but also trace far broader societal and political issues. This is evident in their content—maybe there’s a new railway, a war, an election, a public health crisis—but it’s palpable in the tone and aesthetic, too. Posters encouraging conscription during the World War posters play on male ego and pride, that idea of a “real man” being one with battle scars and stories to tell the kids when he comes home.

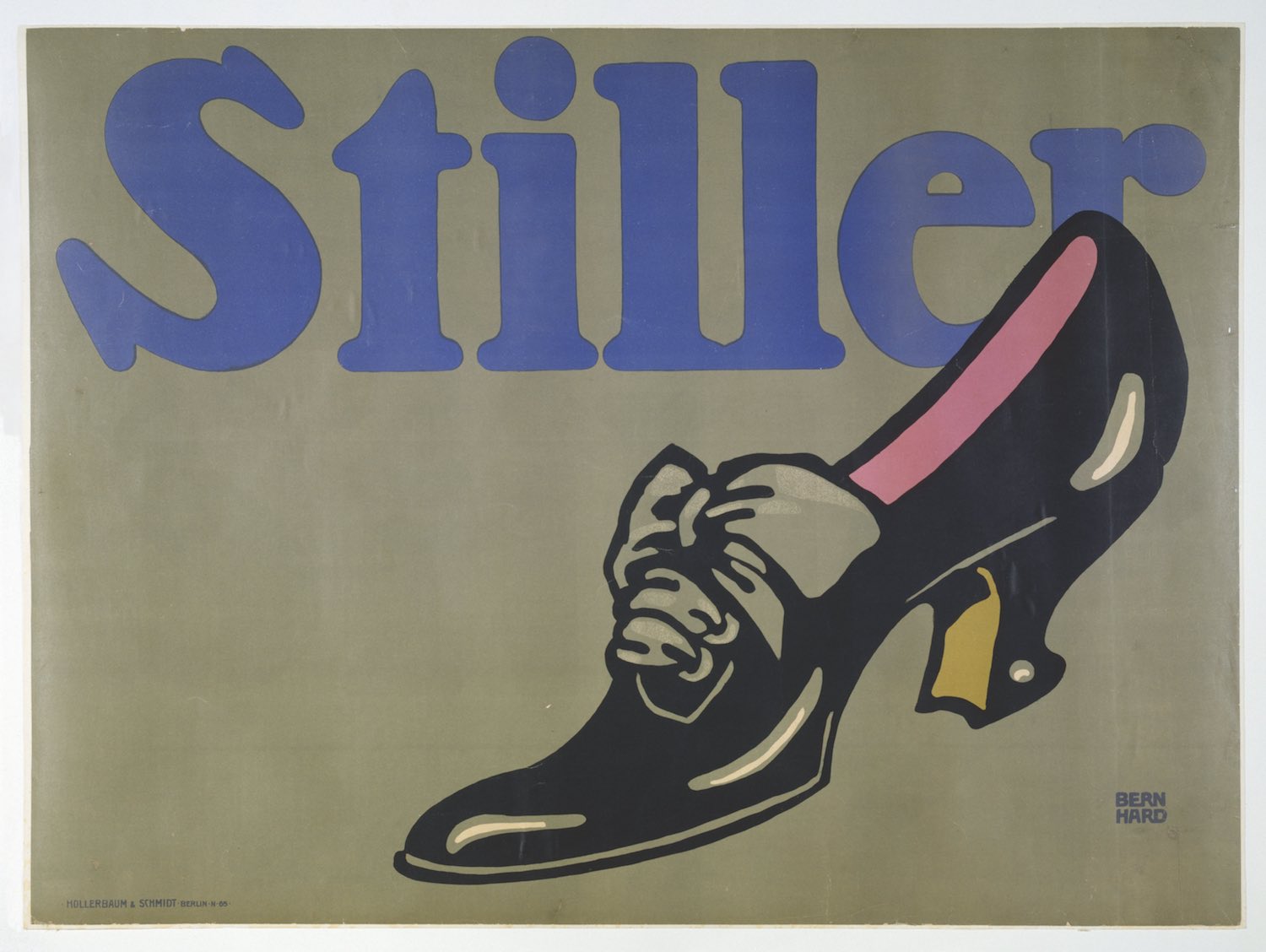

The book’s sevens chapters—performance and entertainment; sport and recreation; art and exhibitions; commerce and consumption; travel and transport; politics, protest and propaganda; and the poster in the digital age—form an exhaustive history of the medium and feature big names from the design world, like Paula Scher, Jonathan Barnbrook, Hapshash and the Coloured Coat, alongside less expected posters. I had no idea how stunning, and how strikingly contemporary, Buckminster Fuller’s graphic work was, for example, until I saw his Save Our Planets, See Our Cities poster from 1971 laid out with far more recent campaigning images.

The Poster also spotlights underrepresented works from protest and activism, such as images by the feminist screen printing collective See Red Women’s workshop, and autonomous artist collective Gran Fury; as well as a gorgeous array of Polish film posters.

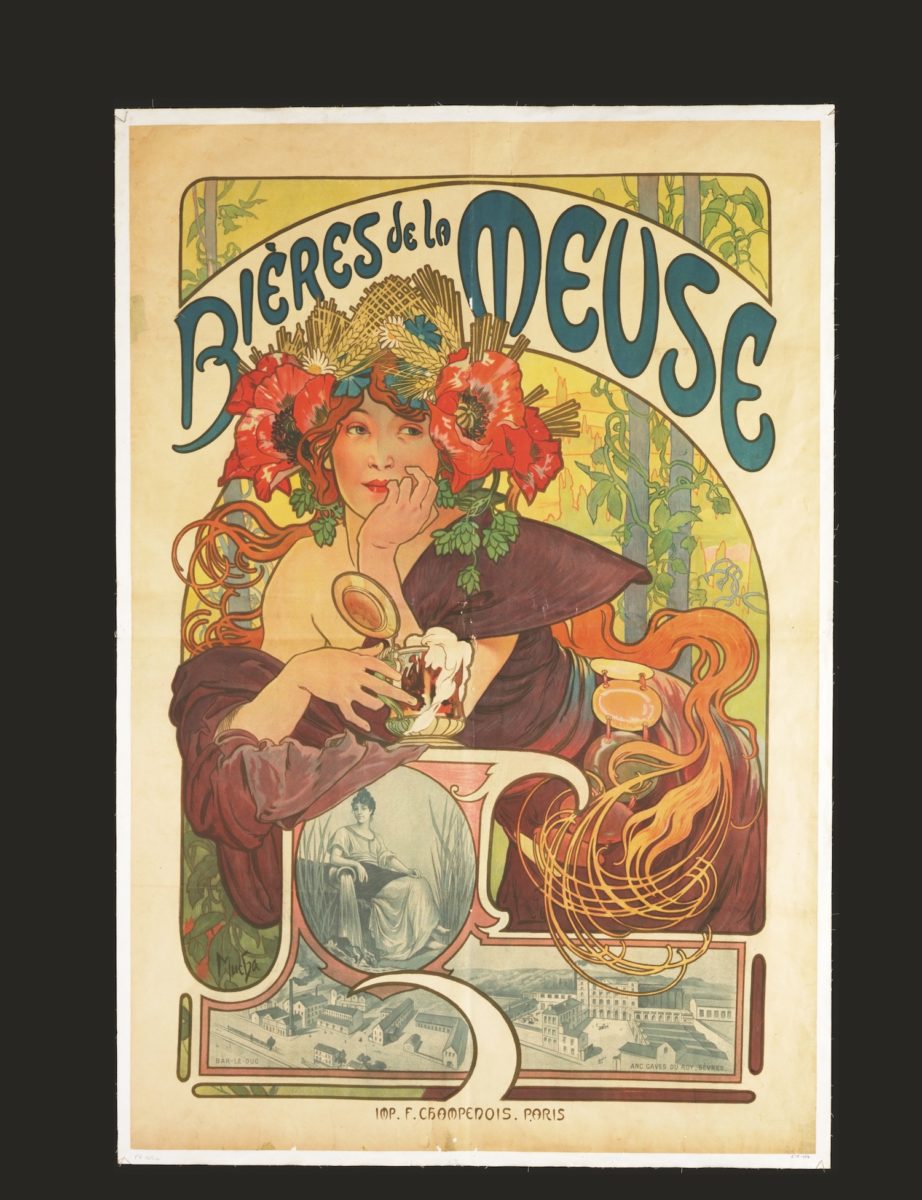

- Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Divan Japonais, France © 2020 Victoria and Albert Museum, London (left); Alphonse Mucha, Bieres de la Meuse, France, 1897 © 2020 Victoria and Albert Museum, London (right)

“While ultimately advertisements are little paper purveyors of capitalism, they’re also often harbingers of doom”

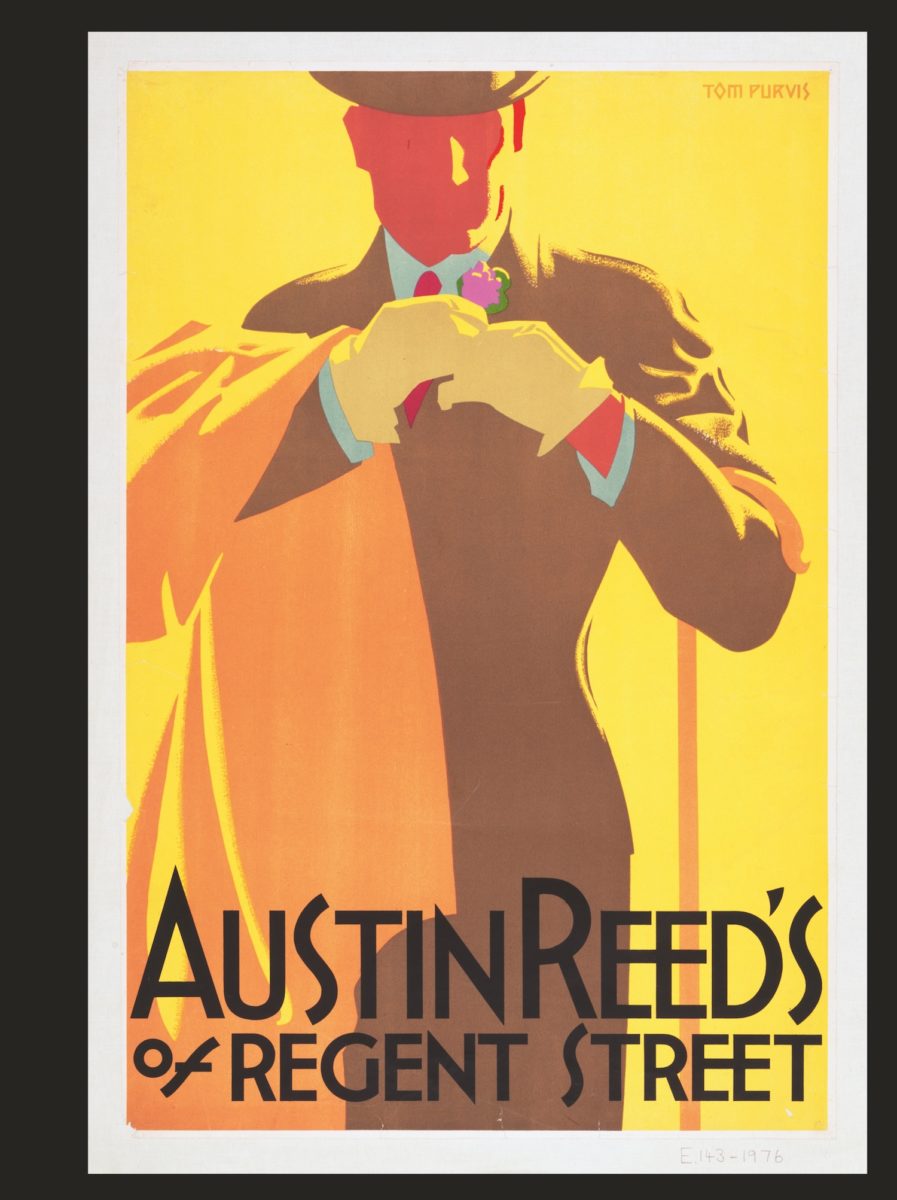

Posters are a unique medium in their democratic nature. Some are made by artists firmly in the artistic canon (Toulouse-Lautrec, Alphonse Mucha, Emory Douglas, Roy Litchenstein, Robert Rauschenberg), while others are the work of people who are either deliberately anonymous or have become so over years thanks to the fact that materials deemed ephemeral, such as protest graphics, are lost. Similarly, designers working for certain brands have often been sidelined, their work becoming that of a company or in-house team rather than their own creativity. Anonymity has also historically been out of choice: some designers, such as those making posers for more outré situations like slightly legally dubious erotic films, wouldn’t wish to have their names made public.

Posters through time act as dual signifiers: while ultimately advertisements are little paper purveyors of capitalism, they’re also often harbingers of doom. As Gill Saunders points out in the books introduction, “fly posting is largely limited to pockets of urban dereliction, often symbolic of economic decline.” The unique democracy of the medium also expands to the financial side of posters: brand or government campaign posters are the result of multibillion pound marketing budgets; those made by grassroots activists, emerging bands or students cost little more than ingenuity and printing ink. The beauty of the poster is in the ease and affordability of its production—a dream for brands, since they can be both highly visible and easily replaced as target audience tastes shift or a next phase of a particular campaign is rolled out.

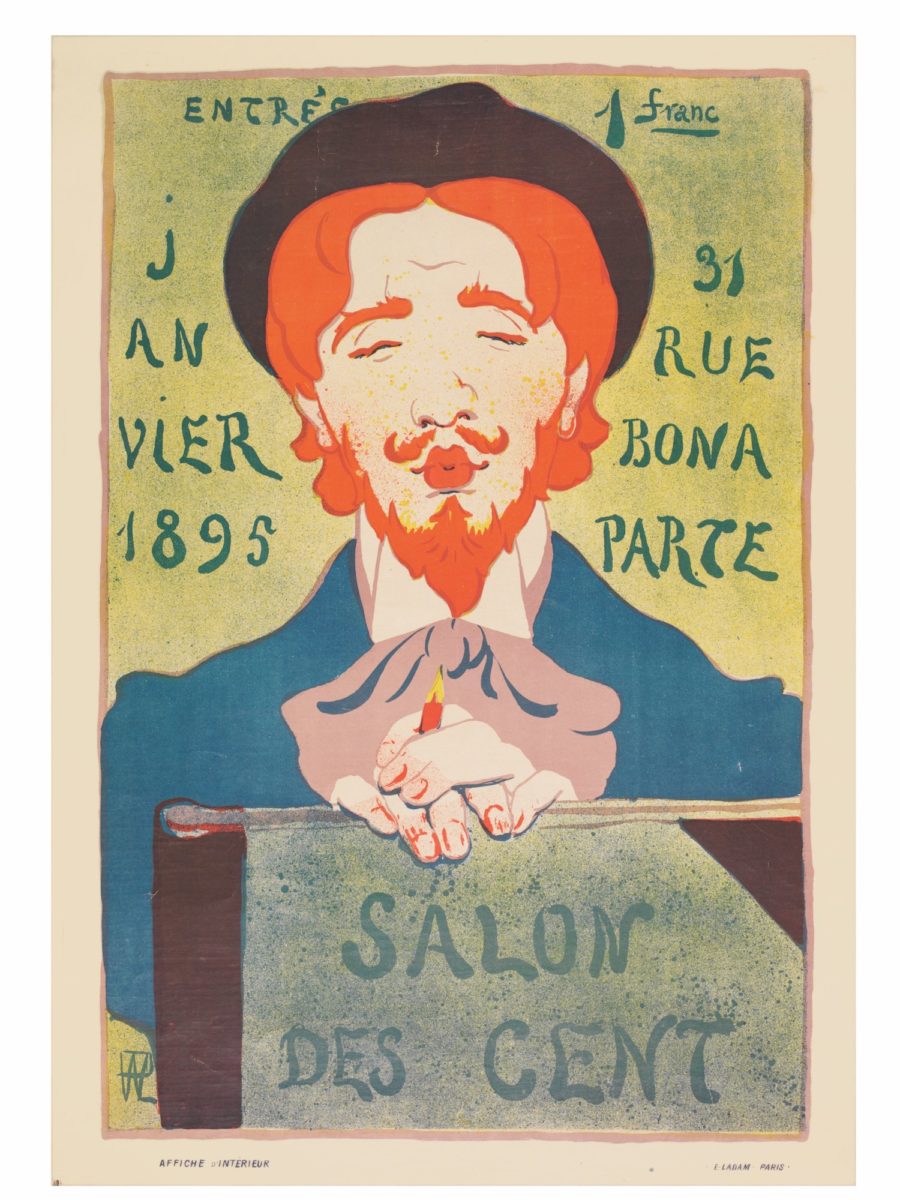

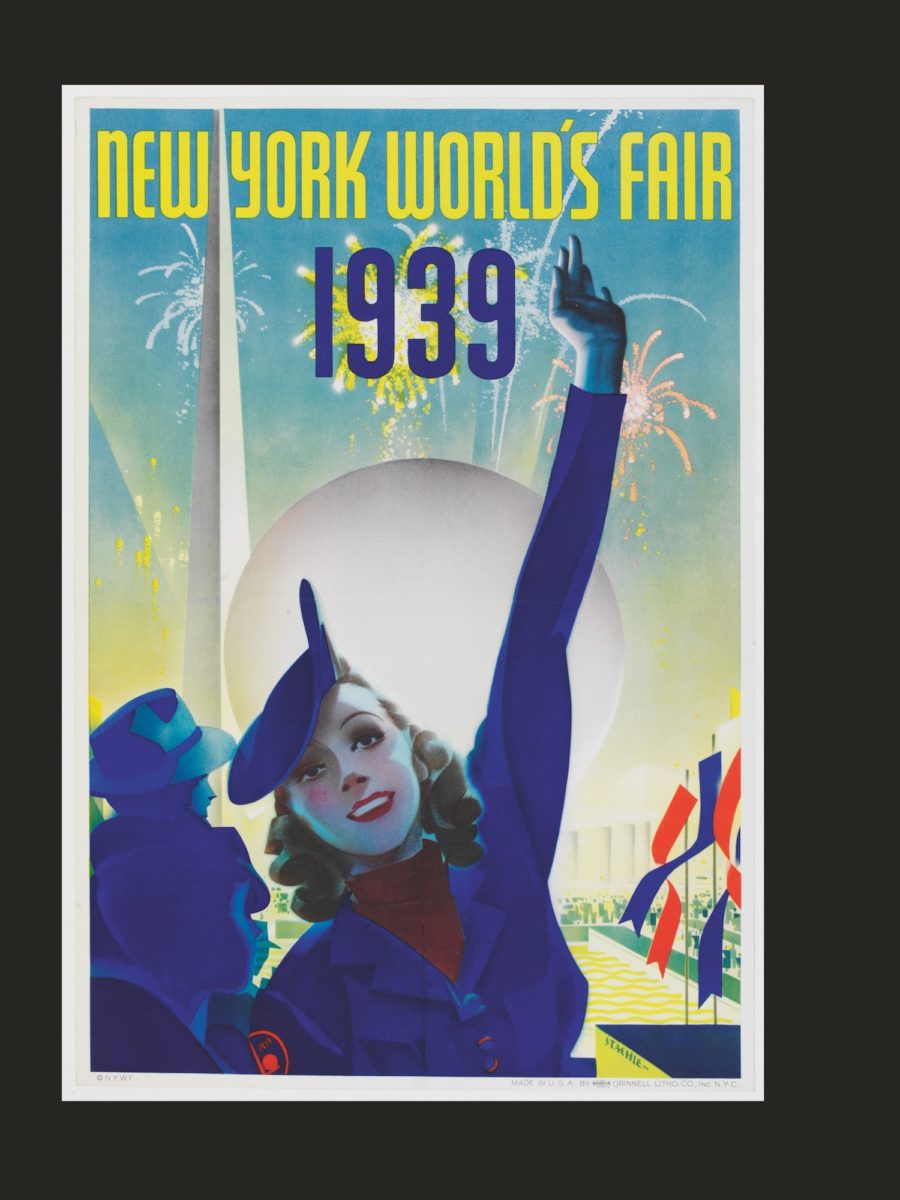

- René Georges Hermann-Paul, Salon des Cent Janvier, Exhibition of the Salon des Cent, 31 Rue Bonaparte, Paris 1895 (left); Albert Staehle,New York World’s Fair © 2020 Victoria and Albert Museum, LondonUSA, 1939 (right)

“The fact that they’re designed to grab someone’s attention, on almost a primitive level, makes them accessible to people to this day“

Yet a good poster is far from easy to make. Those that have been truly successful combine wit, beauty and fitness for purpose. Much as many art nouveau and fin-de-siecle posters have been consigned to the “aunty’s tea towel” realm of design history, there is a reason that picture of a little French black cat has endured. These works are hugely powerful in tracing a moment in time when art and design could be seen as one entity.

The nineteenth and early twentieth century works in the book tell far larger narratives about class divisions, art collecting and the birth of modern consumer culture as we know it; for modern viewers, they demonstrate an effortless blurring between art, graphics, illustration and advertising. Even though the term “graphic design” wasn’t known then in the way we understand it today. From the start, many of these posters were intended as images for people who weren’t naturally engaged with art and design. The fact that they’re designed to grab someone’s attention, on almost a primitive level, makes them accessible to people to this day.

These images, which merge the commercial with a fine art sensibility, underscore a fascinating tenet of poster design: people want to have them in their homes. In effect, anyone with one of those ubiquitous but still rather gorgeous Guinness toucan posters on the wall are acting as little domestic brand ambassadors, often regardless of whether they actively like the product or not: Anyone with, say, a Nirvana poster in their room, however tatty, is a little cog in a record label promo machine. If that’s not incredibly smart guerrilla marketing, I don’t know what is.

The Poster: A Visual History

By Gill Saunders, Margaret Timmers, Catherine Flood and Zorian Clayton

Published by Thames & Hudson and V&A publishing

VISIT WEBSITE