To create a costume for theatre is to dress a character: what time period is it? How wealthy are they? How wild? How buttoned up? How does that character move?

But to create, or decide on, what to wear for performance art is a different matter entirely. While, of course, much performance art is centered on a “character” to clothe; others need a more neutral stance—the performer is simply a conduit for a message or a certain sensibility. Just as the sounds, props, dialogue, movement and space inform the piece as a sort of Gesamtkunstwerk; what the performer(s) dresses in can change the mood of a piece entirely.

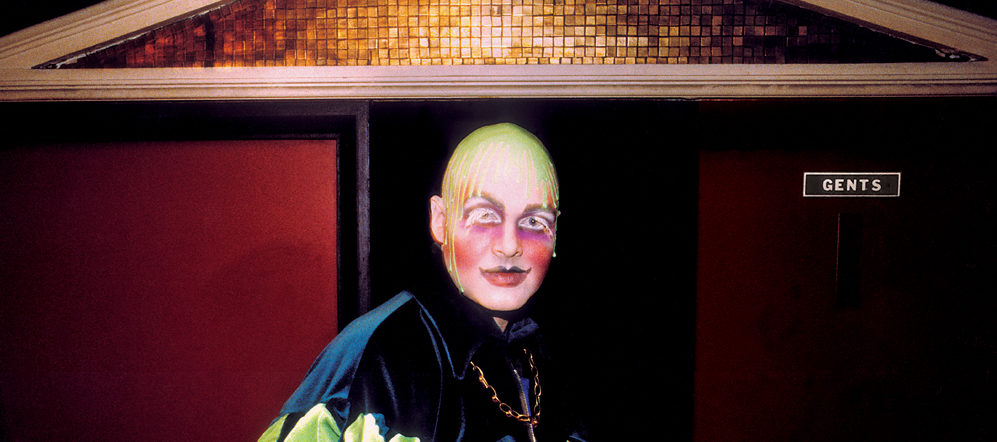

Or, indeed, how the performer dresses—who they are, even—can be as much the artwork as what they perform or make. Look at Leigh Bowery, whose influence on fringe club kid culture and the world of commercial fashion is still keenly felt, twenty-five years since his death. “You see it in fashion, you see it in the underground, you see it in mainstream culture, in RuPaul’s Drag Race,” as Glyn Fussell, founder of LGBTQ+ club culture collective Sink the Pink puts it. Bowery’s entire being was his MO; his outfits, accessories, wild makeup and persona all merged to become his medium in an entirely new, outre, sex-splattered way.

The worlds of fashion and performance are inextricably linked (Gareth Pugh and Alexander McQueen are among the many who’ve been vocal about their love of Bowery), and they don’t just meet on nights out, but in some of the biggest public galleries, too. Jonathan Anderson’s Spanish fashion brand Loewe was behind the costumes for Anthea Hamilton‘s The Squash commission at Tate Britain, for instance. But few artists work with such high-profile collaborators; and here, we investigate five people working at varying ways of approaching what it means to dress themselves, or someone else, for performance art.

Paul Kindersley: A Magpie-like English Eccentric

Body as canvas, and daftness as a communication strategy, informs much of the brilliant work of Paul Kindersley. His work lives and breathes across a duality that mixes the traditions of English eccentricity and the dissemination of ideas and imagery today: Instagram, YouTube (his channel is called The British Are Cumming, of course), Facebook et al. And as with much of YouTube, there’s little here in the way of professional pretence. Footage is often grainy; makeup and costumes are deliciously scattergun and frequently ludicrous. Kindersley has spoken a lot about his magpie-like approach to costumes, rummaging through car boot sales and scrabbling through Saint Martins bins for free fabric to amass a vast hodgepodge of wigs, leotards, even puffy buttoned up Nanna two-pieces. (See above.) Makeup, here, isn’t the “maybe she’s born with it sort”: it’s everywhere, like a preschool painting apron. Which is what makes it so wonderful, really.

Monster Chetwynd: DIY and the Carnivalesque

It’s little surprise to read that Kindersley worked for Monster Chetwynd as a performer for ten years. While her career is hardly amateurish, what’s wonderful about her costumes is that they so often are; thriving in a sense of DIY democracy and unpredictability. Her larger performances are often created in collaboration with a community in which she’s working, have the feeling of a delirious school play at times; surrealistic sitcoms made manifest. They’re anarchic, but optimistic; and you can’t just see the stitches, but the entire machinations. It’s not for everyone, but I find it all utterly joyful. Making great art isn’t about making things perfect, after all.

Indeed, the carnivalesque conviviality of her performances would be diluted were the sets and costumes preened and manicured. The joy in her work often arises from the audience feeling as much part of it all as the cast, feeding off the improvisational aesthetic; or at least, feeling like they could make this stuff themselves (in a positive, not a “my kid could do that” way.) The silliness doesn’t bely the artist’s more serious messages, though; rather delivers them with a spoonful of sugar.

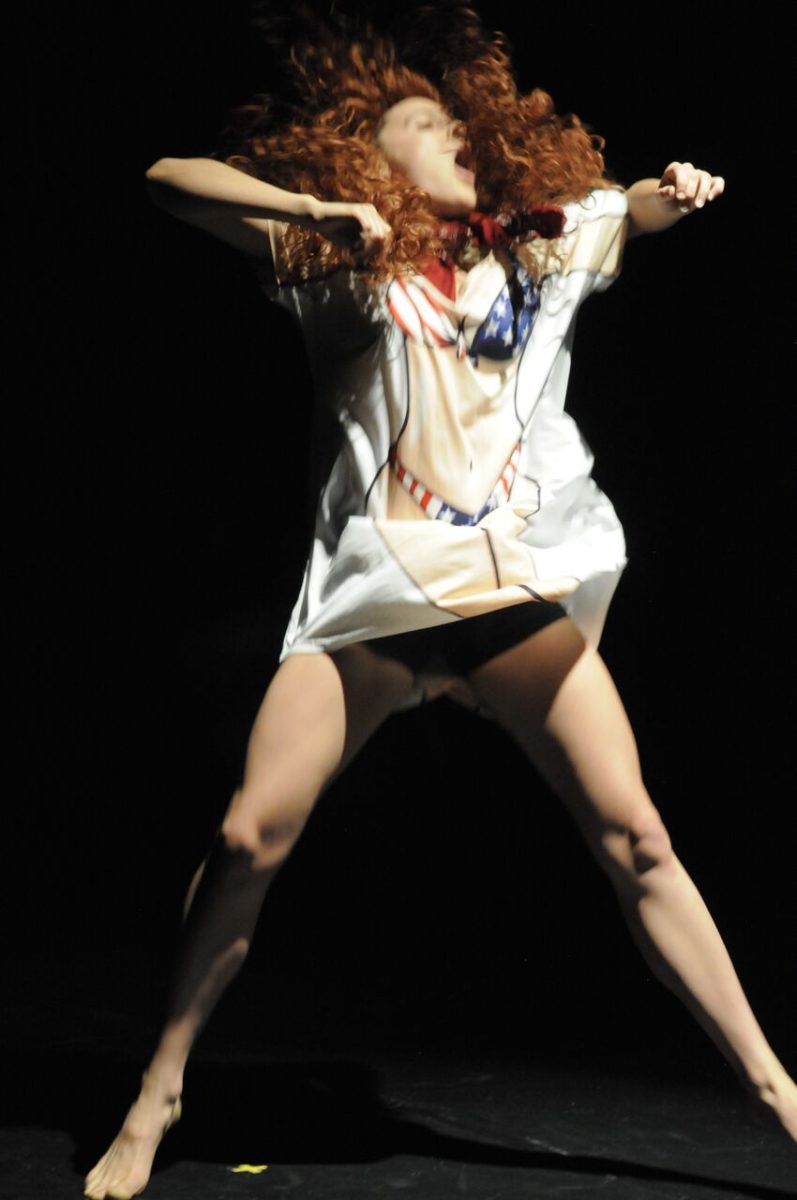

Sophie Yung: Costume as Catalyst

- Sophie Jung, (left) Ballroom Marfa at Äppärät, image courtesy the artist. (right) Paramount VS Tantamount, Image courtesy Kunsthalle Basel

Sophie Jung’s work sometimes even comes into being thanks to a single piece of costumery, or an accoutrement that she initially had no intention of using as part of an artwork. When her partner bought her silver Chanel nail varnish called Liquid Mirror, for instance, “It felt so decadent, and wasn’t even a colour I liked that much, so I just had to make use of it.” This then led to the artist contemplating liquid mirror telescopes, leading to Issac Newton, to Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s battle over who invented calculus; concurrently, she was thinking about liquid mercury, which led to the God of Commerce (Mercury). All of these stories tied together in Jung’s piece Producing My Credentials, which begins with an audience member painting her assistant, Peter’s, nails. “That nail-varnish has become my trademark performance finger-attire since,” says Jung.

While some works are formed, and then the clothing must be decided on as a final thought, many of her works are born of this sort of object-led stream-of-consciousness. “I have no original thought!” she says. “I’d rather respond to another thought; where I have to weave through something.” As such, her art-fits are almost entirely re-appropriations of existing pieces discovered in prop and costume sales. “I find it much more exciting to take a costume someone else made and I have no idea what it was meant for. Then I can detach it from that original signifier and reuse it and reclaim whatever categorization it originally had… I suppose I really enjoy the ‘exquisite corpse’ situation, where I take costumes or objects previously created to signify something, to stand in for an idea or a type, yet without knowing what or which.”

Many of the costumes she “scavenges”, as she puts it, go on to be used in her sculptural works. “The lure of working with found or ‘headhunted’ objects is that you get to uncouple the ‘inherent’ meaning (there is no such thing) from the material… and recode them pluralistically,” says Jung. “You get to show that a particular reading, be it enforced or accidental, is never fossilized into the thing.”

When I saw Jung perform her piece Come Fresh Hell or Fresh High Water at BlainSouthern in London a year or so back, she sported a bodysuit with little nipples on and what she terms “Springsteenian” jeans that “come as close to a casual ‘western’ cultural neutral as I can think”. She’s using the same suit for her piece The Bigger Sleep Rehush (Hush) (2019) at this year’s Block Universe festival. The idea of the suit was to reference the classical nude—Jung was transformed into “a history of European art”, becoming woman as “passive, consumable object”, she says. The nude suit is slightly too small, meaning the “nipples” are prone to slipping. We see her “real” nipples; and she deliberately wants to provoke the questions around why she’s even bothering to wear it: “I like that ambiguity,” she says.

“‘Nude’ becomes a costume, but one you can’t take off”

The costume emerged at a time when she was rewatching John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, which discusses the idea of “naked” as to be oneself, while being “nude” is to be naked to be looked at and denied selfhood and agency. “‘Nude’ becomes a costume, but one you can’t take off,” she says, “so it’s a visual owning off a female body that goes throughout history to now—the way models pose today is based on oil paintings… I was becoming these paintings and this languid woman, but languid in other ways—depressed and alcoholic and patronising.”

I suggest that from a spectator’s point of view, the body and how we clothe it is a far more fractious and politicized process for female-identifying performance artists than their male counterparts.

“Women need to acknowledge their body where men don’t,” Jung agrees. “We never really just ‘stand’ there—we stand as a woman or a female presenting body.” As such, even choosing something “neutral”, casual or unspecific is fraught. “Men are viewed as the neutral; they don’t have to consider the specificities,” she says.

- Sophie Jung, The Bigger Sleep. Image by Julian Salinas

Lu La Loop: Noise and Storytelling

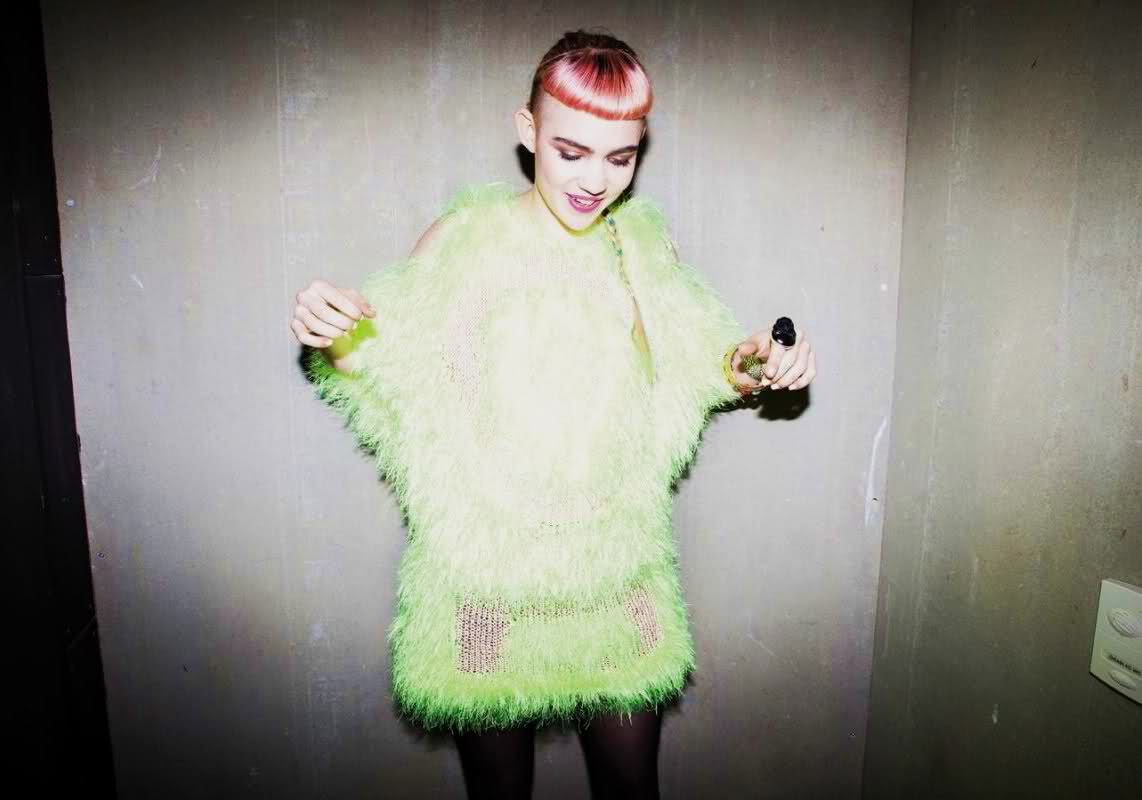

Lucy Eggleton, who works under the fashion and costume brand name Lu La Loop, creates spectacularly sculptural pieces that live and breathe a punkish, wild kinetic energy—both with or without anyone actually in them. Having studied fashion knitwear at Nottingham Trent University, she spent time in London before moving to Berlin around a year ago. She’s long been drawn to clothing for its storytelling capacity as much as its aesthetics. “Everything always had a concept,” she says of her uni work, for which she made all of her own yarns and to which “quite dark music was integral”.

She adds: “I’ve always been story-oriented, and the music and performance part was always something I wanted to do rather than generic knitting.” In her time working for a now-closed Brick Lane boutique, and also in what she terms the “generic mainstream fashion industry”; Loop’s own practise is always distinctly playful and DIY in essence, and superbly crafted in its realization. A big moment for her came in 2014, when Grimes wore one of her creations—which she dubs a “toxic yellow fairy thing”.

- Left: Lu La Loop, design for TT The Artist; Right: Lu La Loop, Zef Alien coat, worn by Kat

I first encountered Loop’s work in all its maximal glory through AJA, one of our 2019 Ones to Watch. The pair met through Loop’s sister, who lived with AJA’s best friend for a time. The rest is big, bold, colourful, leotard-laden history.

“I’m very into artists in general who do things themselves and haven’t boxed themselves into one thing. It has to be unique and fun and quite playful and childlike,” she says. Over the years, her style has developed into something utterly unique but slippery in definition. Nonetheless, people who approach her generally understand what she’s about. Then, the process of creating a new costume usually involves working with a performer to create a moodboard, and a few key words and colours are thrown about to push an idea. One of the most important things for such relationships is trust: “I have to feel comfortable, and you both have to make sure you don’t tread on each others toes,” she says. “It has to be a back and forth; experimenting and being playful as well. Usually really good things come from investigating, just starting something and seeing where it takes you. You get a gut feeling.”

Maria Garcia: Costume as Movement-driver

- Maria Garcia, costume design for Inflatable Trio. Photo by Isaac Obuka.

- Maria Garcia, costume design for Image Action Text. Photo by Taso Papadakis

LA-based Maria Garcia is a costume designer whose work spans film, theatre and live performance art. A few years ago, she began devising her own performance art alongside her ongoing work designing costumes for others. For her, the best projects to be commissioned on are those that allow her to create new “possibilities for the performer and the audience”, she says.

With her own pieces, Garcia says she starts “with a question or montage of images in my head. It’s really nice being in control of that investigation.”

“If I’m working on something where you get to experiment, and there’s more freedom and if the costume is an important part of the piece from inception, that’s definitely enjoyable.”

For Garcia, the most enjoyable projects as a designer are those in which she has the freedom to experiment, and in which “the costume is an important part of the piece from inception”. She cites her work for dancer Laurel Jenkins as exemplifying a collaboration that lets the “costume be the driver in the piece”, she says. “She allows for the costumes to feel alive and be used intentionally—she’s not just someone ‘being dressed’.”

As someone working on both sides of the costuming and performing dialogue, Garcia says the main considerations in any design are broadly similar: who’s wearing it, how it will look in certain lighting, the sounds it makes, how it moves. Other than that, though, she says there are no definitive rights or wrongs when it comes to designing for performance art. “I don’t like to rule anything out, particularly with performance art,” she says. “Even when something might look completely awful and feel awful, that might be the point.”