A luminescent reptilian eyeball gazes up from a super-sized, pistachio-hued palm, surveying the crumbling TTT building in central Athens. This elegant hand is connected to a stuffed velvet snake that skirts around oozing pink blobs, copper pyramids and snakeskin-covered footballs as it crosses the ziggurat-like installation Psy Chic Anem One by Tai Shani. Unfurling on the ground floor of the five-story Athens Biennale’s main home, the piece is a rare moment of arcane, abstracted poetry.

Inaugurated in 2005, the Athens Biennale has become synonymous with punchy, often controversial exhibitions that question the power structures governing the art world, notions of public and democracy, and this year in particular, the fluctuating position of Athens within the global art economy. With almost one hundred participants—two-thirds of these from other countries—the Sixth Athens Biennale (AB6), also known as Anti, encapsulates both global and Athenian concerns.

Themes of seasteading (creating permanent, sea-based dwellings), cryptocurrency, the self-care economy, bio-hacking, the rise of the alt right and alternative belief systems run through the Biennale like a parafiction bingo card. Dominated by video art, the labyrinthine halls of TTT become a psychedelic chamber of globalized anxiety, where interspecies romance, wellness boot camps, Pikachu-painted taxidermy and sexually frustrated cartoons converge.

Although all four of AB6’s outposts consist of abandoned buildings, including an former hotel turned movie theatre and an old library reborn as an inflatable pig pen, the pre-loaded bureaucratic surrealism of TTT and its office floor plan makes it the perfect site for such a mixed gathering of work.

“The building reflects biennale culture—offering up the immediate curiosity and capital of the art world glitterati, but risking bleeding dry the qualities that make its host city appealing“

Built in 1931, the TTT building is defined by its hybrid neoclassical-modernist architectural style, one that embodied the futuristic dreams of its lodgers–the state-owned Telecommunications, Telegrams and Post (TTT) Company. Until few years ago, Athenians would come to this building to pay their phone bills. Zoom back three-quarters of a century, and the place was engulfed in the first worker strike under Nazi occupation of Greece in World War II.

In its present state—hinging between seductive ruin porn and its impending future conversion into a luxury hotel—the building becomes a space in which to address all that is Athenian, and all that is global, about the complicated role of disaster tourism in what is termed a “post-crisis Athens” by AB6’s press release. The building also reflects the multi-headed beast of biennale culture—that which offers up the immediate curiosity and capital of the art world glitterati, but risks eventually bleeding dry the very qualities that make its host city appealing.

Ascending the winding staircase of TTT, I land in the “best-self” training room of The Agency. Self-care phrases spray-painted on the wall counter the obsessively composed scenes of beauty products on the counter closest to me. From Pez dispensers to felt tip pens, highlighter sets, whitening creams and protein bars, there is physically and politically a lot on the table—most of which feels left in the dark. Almost tripping over a glistening marble print laminated podium and onto a sickly green vinyl floor, I realize this installation is a stage set for one of the performances happening throughout AB6.

For those lucky enough to see the neon nightmare of Medusa Bionic Rise (2017-18) in action, I hope this imagery lives up to the sweating, metal-pumping, dubstep-blasting, glowpaint-filled hellhole of a workout routine. A #fitspo parody dripping in Berliner irony (entering a K-hole at Berghain is great cardio, right?), the performance is advertised as a “a visual walkthrough to post-humanism,” and I’m not convinced. The whole set-up feels like a janky Instagram algorithm regurgitated into an ambient gym backdrop—with some nightclub aesthetics thrown in and blended with Star Trek hairstyles for good measure. Next.

Actually, we’re not done with athletic post-humanism—I hit Nike (2018) by Greek-born, LA-based artist Theo Triantafyllidis and it’s ticking all the right boxes. Imagine the incredible hulk moved to LA, got a sex change and became a lifestyle blogger: he would look a lot like Triantafyllidis’s Nike. Truly the studio visit to end all studio visits, I follow the blue-haired, jacked-up avatar around as she conjures a new work by chucking boulders and found objects including traffic cones (so LA) across her studio in a fit of creative rage. Muttering a convoluted artist’s statement in short bursts throughout the rampage, Nike perfectly parodies the now-ancient idea of the genius artist flying solo in the studio.

“In many of these works, the moral standpoint of the artist remains unclear. Are they replicating these violent bigoted viewpoints or critiquing them?”

Nike stands on the precipice of the CGI marathon that at times felt like it had the Biennale in a chokehold. I’m still unsure why such a large portion of work addressing contemporary alt-right and neo-fascist politics takes computer-rendered moving image as its medium of choice. Perhaps the shared digital sphere enables these artists to get closer to their source, for better or for worse; perhaps creating these scenes through an immaterial and at times automated software—as opposed to strict documentation of IRL happenings—allows the parafictional element of the work to thrive in its ambiguity.

That certainly seems to be the case with the included works by Ed Fornieles and Joey Holder; meanwhileThe Seasteaders, by Jacob Hurwitz-Goodman and Daniel Keller, follows its neoliberal gods to their source. The video installation is split across several screens, and I watch in mute horror as throngs of [PayPal founder] Peter Thiel disciples in Hawaiian shirts are seen mingling with locals whose land they will be re-colonizing as soon as 2020 in order to build their floating city off its coast. More awkward than any middle school dance, this grotesque scene is replaced by equally grotesque, glitzy prototypes of these “Seasteaders’” tax-free, politician-free artificial islands. Interviews with members of the Seasteading community, in which they proudly defend their new strain of hyper-capitalism, is the nightmarish icing on the tech-bro cake.

In many of these works, the moral standpoint of the artist remains unclear. Are they replicating these violent bigoted viewpoints or critiquing them? It’s impossible to tell, and Anti’s curators are happy to take that opacity on board: “Everything today is Anti,” says co-curator Poka-Yio. “We are trying to problematize the situation, in a way that is critical but not detached from its protagonists.” The Biennale’s ethics were certainly problematized earlier this year when British artist Luke Turner pulled out of the programme in September, citing anti-Semitic threats made against him by another exhibiting artist, Daniel Keller. Finding no hard evidence of Turner’s claim, the Biennale allowed Keller to remain.

But not everything at AB6 is CGI and post-human post-ethics. The Civil Financial Regulation Office (2018) by the Berlin-based Peng! Collective is a site-specific durational performance that sees six Greek students calling up the IMF and European Central Bank in order to speak about the global financial crisis. Call centre employees are paid German minimum wage (€8.84/hr), raising the stakes of the German-Greek relations (Merkel held a stringent stance on the Athens bailout) while also flagging the issue of un/paid labor in the art world often swept under the rug by large institutions.

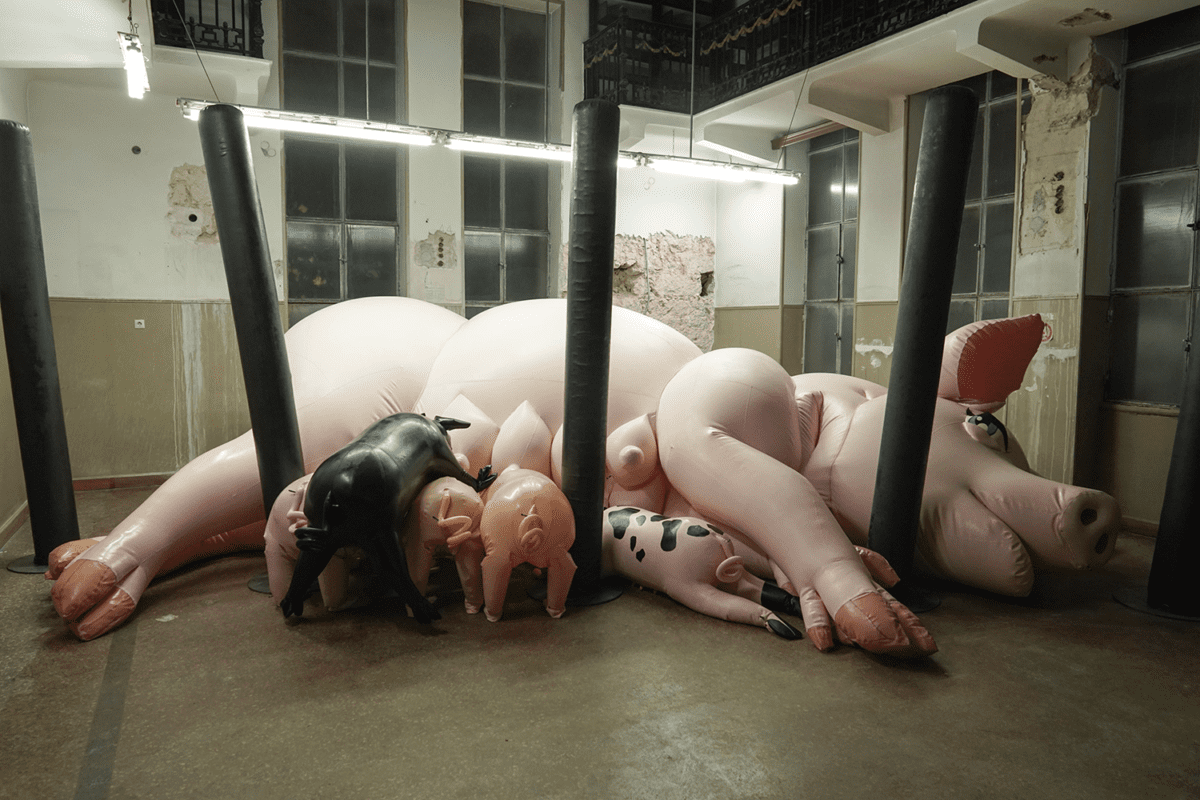

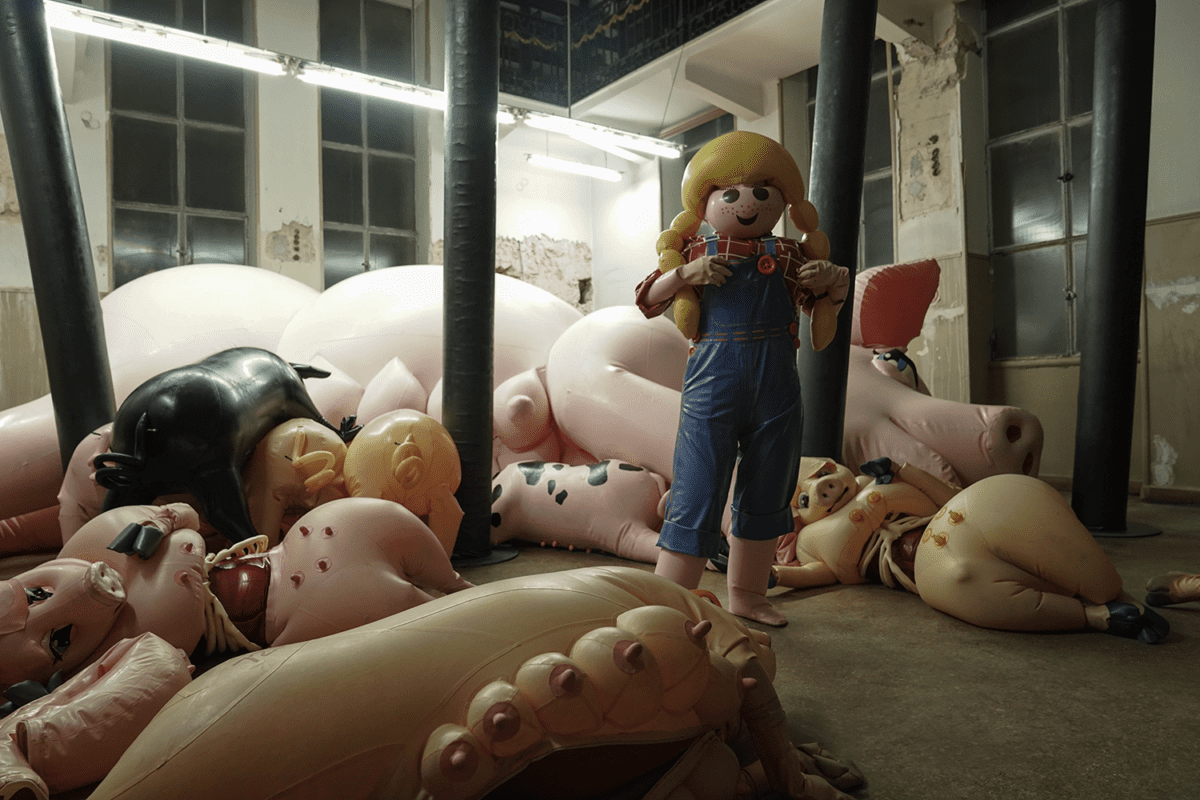

If you can power through the heaps of video, Nicole Wermers’ quietly profound Moodboards (2018) awaits you on the top floor. A series of baby changing stations blinged-out with trendy terrazzo inlay, Moodboards picks up on the themes of wellness culture and Instagram envy on steroids. But by superimposing desirable, luxe interiors with the utilitarian baby station—and the unbelievably-still-taboo subject of motherhood—Wermers strikes a deeper, more universal chord than the Bitcoin bros downstairs, no renderings needed. Same goes with Japanese artist Saeborg’s inflatable Pigpen (2016), with its soft and fleshy silicone opening enduring a cycle of birth in every performance.

- Saeborg, Pigpen, 2016, latex sculpture

- Saeborg, Pigpen, 2016, latex sculpture

Among all the slick avatars and simulated realities, alt-right agendas and post-apocalyptic aesthetics defining AB6, birth and new forms of intimacy are redeeming and powerful counter-themes. They radiate against the prevailing landscape of stark post-humanist ideologies that isolate the viewer as much as they intend to inform them—sending a signal that Anti might not be the message we need, after all.