Painting about motherhood has always been natural for Madeleine Donahue, whose first painting, created when the artist was aged fifteen, was “a large imagined portrait of my mother holding me as a child”. Many contemporary artists have made works about their relationships with their mothers—absent or present, harmonious or diabolical. Psychoanalytical interpretations of art might even suggest that all art is shaped by this fundamental relationship—whether conscious or not.

Yet relatively few artists have ventured into the other side of motherhood to narrate their experiences as mothers. When Donahue became pregnant with her daughter Twyla, who was born in the summer of 2016, her interest in motherhood in her work shifted in a new direction. “While I was pregnant, I read everything I could find about birth. It was such a mysterious experience and I wanted to know as much as possible. I could not believe how little I knew about my own body and some of this led to the work I make now,” Donahue tells me.

“We worked with an amazing doula, Leigh Kader. She was so important and she and my husband helped me labour at home in Brooklyn for as long as possible, which was about thirty hours, before heading to the hospital. My daughter was born after about fifty hours. I really feel like I looked death straight in the eye! It took a while for the doctors to let me hold her and those minutes (or that minute) felt like an eternity,” she recalls of the birth.

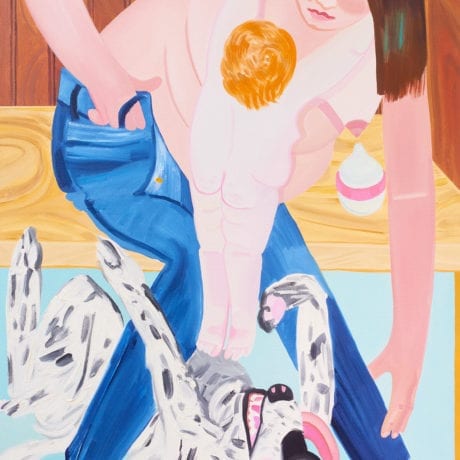

In Donahue’s paintings, recurrent scenes are familiar to me in my own experience of motherhood: a tangle of limbs, hair being tugged by tiny hands, a precarious balance between half-dressed and half-caressed. The large, protruding nipples she paints, standing to attention, ready to feed, speak of the “boob signal”—that feeling every breastfeeding mother knows well—as your breasts harden with supplies of life-changing milk.

“I really feel like I looked death straight in the eye! It took a while for the doctors to let me hold her and those minutes”

Donahue paints about motherhood with humour and with a compelling flat pop aesthetic. “My focus is being honest with my feelings and with the experiences that inspire me. I try to be forgiving of myself in the process. The work is bare and I am opening myself up through the work,” she explains. “That is scary—but I don’t necessarily think about that as a stigma or coming from the stigma of parenting and birth.”

Donahue might not deliberately address the stigma of birth and motherhood in art, but it exists nonetheless. The names she mentions when I ask her which artists she admires who have made art about the subject are familiar: Louise Bourgeois, Alice Neel, Chantal Joffe, Paula Modersohn-Becker and “Marlene Dumas’s baby paintings”. She also cites the seventy-six-year-old American artist, Katherine Bradford, who Donahue knows personally. “I love chats with her about her own experiences as an artist parent.”

Combining the absurdity and fun, the physical pain and the playfulness of being a mother in intimate, private scenes, Donahue’s work has solicited warm reactions from the public. “People seem to really connect to the humour and honesty,” she tells me.

Drawing on her personal experiences, Donahue says, “at a certain point, instead of shaking off parenting in the studio, I just decided to go in and be like, “OK, this happened today, I’m going to draw it.” That turned into this really fun experience of drawing and painting my perception of motherhood.”

“People seem to really connect to the humour and honesty”

“An example is bathing,” she adds. “My daughter hates taking a bath but she also wants to be with me while I try and bathe (and of course all the time). For any mother (or parent), taking a bath or shower is one of the symbols of the hardship of parenting. I’ve found it to be one of the funnier and more challenging experiences. This gave me a point of inspiration. Having fun in the studio is really important and all of my work evolves from time spent in my studio.”

Balancing her studio practice with having a young child is something that has also affected the way Donahue works, like many other women who work in any field. “My practice is completely changed. Time has a new meaning. I have a very limited amount of time. I’ve found that I work better this way. I am way more productive. When I get into the studio I get right to work. I don’t allow myself to sit and wonder what to make, I just start drawing or painting. I keep track of supplies so I have what I need while I’m working. I appreciate the personal time and space of my studio. When I am at home, I’m focused on parenting and when I’m in the studio I am 100% focused on making art.”

There’s no doubt that having a child changes your life—and your relationship to all the things in it, from the banal to the sublime. Donahue hasn’t painted directly about childbirth—a subject that is still virtually absent in the history of art, and in the art being made today. I ask her why she thinks that is.

“The craziest thing is that everyone is here as a result of birth, in some way or another, and yet it is not something that people address in art. How are we not talking about it? It does seem we are living in a time where people are more open to talking about things that used to be taboo or controversial.”

Making (It) Work

From 22 January to 7 February 2019 at Oliver Art Center, California College of the Arts, Oakland

VISIT WEBSITE