Is there any subject as unpopular and uncommercial in contemporary art as birth? When artist, curator and mother of two Helen Knowles started the Birth Rites Collection she wanted to address the way we understand birth, by looking at its representations. The collection is the only one of its kind, comprising more than eighty artworks by contemporary artists on the subject of childbirth.

Knowles started the project in 2006, following the birth of her own children, (now fourteen and sixteen) in order “to explore the politics and practice of childbirth”. Her research has evolved substantially as the collection has grown; in 2017 it moved from Salford to King’s College London, where it is now displayed across various buildings, hosted by the department of midwifery, part of the Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery & Palliative Care. Knowles runs regular tours of the collection, alongside artist Hermione Wiltshire and midwife Eleanor Featherby, and they organise talks and events.

“I consider this project an artwork in a sense: it’s about collaboration, and raising the status of this kind of work by using the economic tool of a collection. I’m really interested in how value is created with this kind of work, work that challenges people on a fundamental level,” Knowles tells me, talking on Skype from Manchester where she lives.

“In order for women or marginalized groups to gain recognition there needs to be activism”

“My first birth was an emergency cesarean, and that kind of catapulted me into this subject. My second was a home birth, and it was after that that I started to bring together lots of different birth practitioners, and paired them with artists—and that’s how I put together the first exhibition.” Five participating artists spent time with midwives, doulas and obstetricians, attending births and witnessing how diverse the birth experience can be, each creating works in response. It was the resulting commissions that started the collection.

The collection is non-profit, and the works aren’t for sale—they enter the collection either by donation or public funding. The economic model itself is an important part of Birth Rites. “In order for women or marginalized groups to gain recognition there needs to be activism; artists need to donate their works. This collection wouldn’t exist otherwise.” Since works on childbirth—an act that is widely considered to be unpleasant to look at—are not viable for the art market, the collection remains entirely unique in the UK, preserving an archive of contemporary images on the subject.

It’s so rare that we encounter art on birth, but Knowles puts this down to the lack of space for presenting it, rather than an absence of artists approaching the subject. The collection includes a collaborative textile work by Judy Chicago, Creation of the World, part of the Birth Project, 1985, made with 150 needleworkers in the US. Another key work is Ana Casa Broda’s Kinderwunsch, made up of twenty-eight images. Broda donated the work to Birth Rites in 2014, when it was housed at Salford University.

“I’ve found that loads and loads of women and men make work about this at some point in their life. The point is where are they going to show it? It’s a taboo subject and it’s not commercial. It’s not that there’s a dearth of imagery but that artists haven’t got contexts.”

The censorship Knowles has encountered herself in putting up the collection proves that the world isn’t ready—yet—to accept birth as part of our visual culture, and something we need to look at. While exhibitions like The Photographer’s Gallery 2014 Home Truths displayed many direct, frontal work on birth, there have been no significant public shows in galleries or museums in the UK since. Knowles always hangs the collection in an educational context. “What I’m interested in is in the way an artwork can have a dual function, a pedagogic element and it is an artwork,” she explains. But the responses to the works even in an environment of medics has been surprisingly reticent. At Salford University, ten of Broda’s images were censored from public view.

“There is a gap, particularly in the Western world, because we’ve come so far removed from the experience of pregnancy and birth”

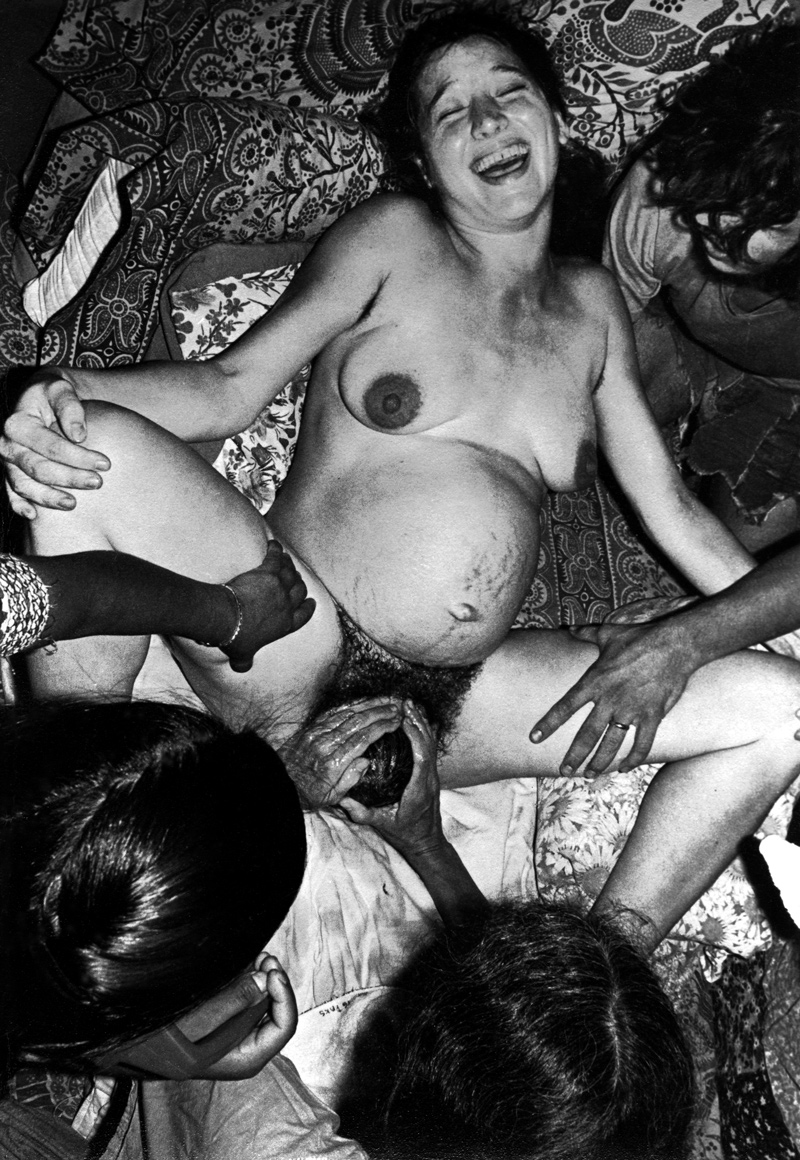

One image has been particularly problematic, depicting a woman experiencing sexual pleasure while giving birth. The work, Terese Crowning in Ecstatic Childbirth is an image appropriated by the artist Hermione Wiltshire from Ina May Gaskin’s book A Guide to Childbirth. It caused, Knowles explains, “a downright furore” when she hung it at at The Glasgow Science Centre. “The staff insisted it could not be shown in the entrance.”

In an essay about the incident, published in Feminism and Museums, Knowles writes: “No one was really willing to answer my question—why? This intrigued me. What was it about this particular image of Terese that caused so much consternation? It was obvious that the Glasgow Science Centre felt that they needed to protect their audience. But why did they need to protect them from a photograph of a birthing woman with an expression of euphoria and elation as the baby’s head emerges from between her legs?”

In trying to unpick why certain images provoke these kind of responses, Knowles says, “there is a gap, particularly in the Western world, because we’ve come so far removed from the experience of pregnancy and birth—now women see it and experience it via YouTube. So that changes the nature of how we understand it.”

“What this collection is about is providing that information for everybody, in order to understand what happens to our bodies, visually.” We recount birth stories to one another, woman to woman, in private, down through generations, “but when you have the chance to see something it changes it”.

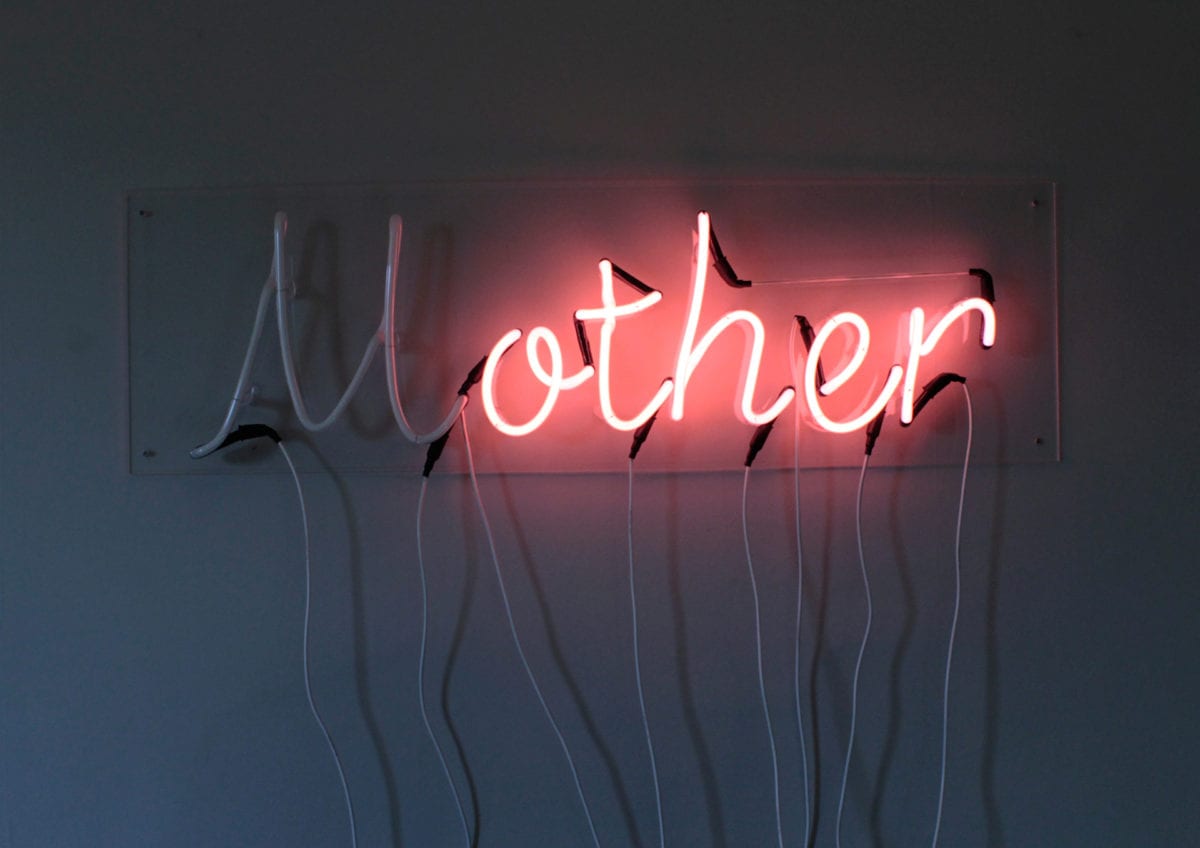

- Lauren McLaughlin, A Conflict of Interests, 2016. Neon. Courtesy of Birth Rites Collection

Knowles is currently working on a day of performances on non-binary and motherhood. “I’m always open to many different perspectives; the point of the collection is supposed to be completely broad—it’s about expressing an array of opinions, and it’s a forum for debate.” BRC has also just announced its latest resident, Lauren McLaughlin, who will work at the midwifery school at Kings. This kind of personal engagement with the actual act of childbirth in a world where we increasingly detach from physical experience also seems to be one of the most important initiatives Birth Rites has facilitated; challenging perceptions of birth and what it means has to begin there.

“People make work about death, illness, love…” Knowles reflects, “birth is another part of life and it should be treated equally and with the same respect. It’s absolutely bizarre that we live in a society that doesn’t do that.”